This round-up is part of Harvard Magazine’s series “At Home with Harvard,” a guide to what to read, watch, listen to, and do while social distancing. Read the prior pieces, featuring stories about the history of women at Harvard, the climate crisis, great legal scholars, and more, here.

In light of the current, widespread protests over the death of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer, we’ve compiled some of Harvard Magazine’s extensive coverage of racism, inequality, and incarceration. We hope these stories offer readers a sense of history and context for understanding today’s harrowing events.

Photograph by iStock Images

Alec Karakatsanis, J.D. ’08, founder of the Civil Rights Corps, dedicated to effecting fundamental changes in America’s criminal-justice system, has become a fierce litigator against “human caging” and “wealth-based detention.” He has launched fundamental challenges to such procedures as money bail, which can be devastating for lower-income citizens—in effect resulting in their being held in debtors’ prison. Of one landmark case and its outcome, he said in our feature “Criminal Injustice”: “There was no good reason those people were in jail….They were all there just because they couldn’t afford a few hundred dollars.” The way the system plays out today, he says, U.S. incarceration is not random: “We’re doing it to human beings and bodies that belong to particular groups. We’re doing it at astronomical rates to people of color and impoverished communities. We are putting black people in cages at rates six times that of South Africa at the height of apartheid.” Read this powerful profile by Michael Zuckerman ’10, J.D. ’17, now a public-interest lawyer himself—following clerkships for Judge Karen Nelson Moore of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and Justice Sonia Sotomayor of the U.S. Supreme Court.

~John S. Rosenberg, Editor

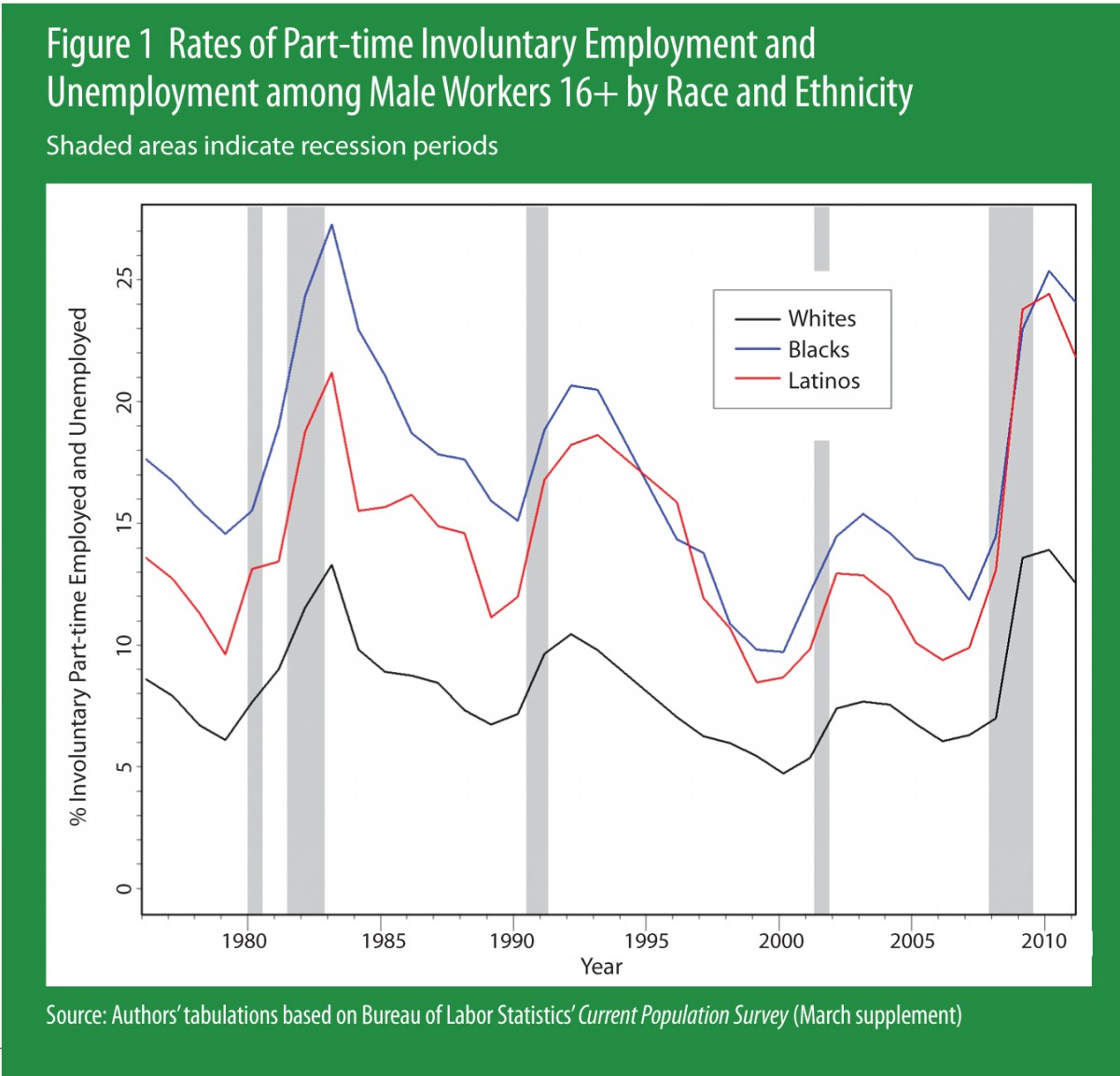

The U.S. economy has shed low-skill jobs in the last 50 years as a result of forces including deregulation, globalization, and declining unionization. To move into the middle class, young people must have access to the education and training that will let them perform the high-skill jobs that increasingly dominate the modern economic landscape. In “The Urban Jobs Crisis,” a piece that has renewed relevance in a pandemic-induced economic collapse, sociologist William Julius Wilson and colleagues pointed out that the Great Recession of 2007-2009 magnified the job-skills gap. They called then for a comprehensive schools and jobs initiative to address longstanding problems of unequal access to employment. “Without coordinated, deliberate intervention at the policy level,” they wrote, the outlook for the economic future of disproportionately black and Latino urban poor is “very bleak indeed.”

~Jonathan Shaw, Managing Editor

Elizabeth Hinton

Photograph by Stu Rosner

In her book From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, historian Elizabeth Hinton details how mass incarceration became a bipartisan project, with both Republican and Democratic presidential administrations contributing new enforcement measures over the decades—new mechanisms of surveillance and punishment. And it all began, she writes, in 1965 with Lyndon Johnson. One month after the violent uprisings in Los Angeles’s Watts neighborhood, he signed a bill into law that allowed federal money to be funneled into local police departments. The funding increased manpower, modernized forces—and armed officers with military-grade weapons. It also helped widen local law-enforcement patrols and surveillance operations in cities with large African-American populations. From then on, Hinton explains, law enforcement became a ubiquitous part of the social and political landscape in poor black neighborhoods. Strategies intended to identify residents at risk of becoming criminals encouraged authorities to provoke interactions with them, creating a feedback loop of crime and enforcement. That feedback loop continues to the present, when the United States, with 5 percent of the world’s population, has 25 percent of its prisoners—nearly two-thirds of whom are African American or Latino.

Khalil Gibran Muhammad

Photograph by Stu Rosner

Khalil Gibran Muhammad’s book The Condemnation of Blackness is an essential text for understanding America’s contemporary relationship to crime and race. The belief that African Americans are innately more criminal is deeply ingrained in this country and has profoundly shaped its public policies, and Muhammad traces that belief to a particular moment in history: the 1890 census, which found that black Americans made up 12 percent of the population but 30 percent of its prison inmates. Racially motivated policing and surveillance were common by the 1890s, but white social scientists took the raw data as objective and incontrovertible. “From this moment forward,” Muhammad writes, “notions about blacks as criminals materialized in national debates about the fundamental racial and cultural differences” between blacks and whites. Black criminality became a widely accepted justification for prejudice, discrimination, and “racial violence as an instrument of public safety.”

Mary T. Bassett and Khalil Gibran Muhammad

The COVID-19 outbreak has laid bare longstanding racial inequalities in the United States—not only in health care, but also in the economy and community infrastructure. Among black and Latino Americans, infection rates are much higher than for whites, and so are mortality rates. A few weeks ago, Harvard historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad and public-health professor Mary T. Bassett convened over Zoom to dissect some of the factors influencing the American pandemic experience. They delved into the history of public health, the long record of divestment from neighborhoods of color—and the role that policing plays in the pandemic’s racial dynamic: black communities, which tend to have greater exposure to the virus, are also the places where law enforcement is more likely to be involved in the public-health response. “There couldn’t be a more revealing intersection of public health and policing,” said Muhammad.

~Lydialyle Gibson, Associate Editor

Attorney Avis Buchanan, J.D. ’81, director of the Public Defender Service (PDS) in Washington, D.C., has spent her career providing legal assistance to those who need it. PDS represents adults and minors accused of the most serious, complex felony cases, but who cannot afford legal counsel. “People here are offended by the government’s overuse or arbitrary use of power,” she says of PDS staff and attorneys. “Just because you say I should go to jail, just because you say I did something wrong and have the capacity to deprive me of my freedom,” she adds, “doesn’t mean you’re right.” Her views are also influenced by her sense of fairness and faith as a Seventh-Day Adventist. “We are often a client’s last friend, the only one standing in his or her corner. This work is important because we help address the imbalance of resources for poor people versus rich people.”

~Nell Porter Brown, Assistant Editor/Manager, Special Sections

Walter Johnson

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Writing “From Lewis and Clark to Michael Brown,” a profile of historian Walter Johnson and his recent work on St. Louis, was a deeply personal experience for me as a St. Louisan. After the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown in the suburb of Ferguson, Missouri, in 2014, Johnson dug deep into the city’s structural inequality. A widely reported 2015 U.S. Justice Department report found that Ferguson’s budget relied heavily on collecting fines from its black residents for minor infractions like jaywalking. Meanwhile, Johnson argues, Ferguson was home to a Fortune 500 company that wasn’t paying its fair share of taxes. “How is it that you can have a Fortune 500 company in a city where they’re farming poor black motorists for traffic tickets for revenue?” he said to me. “It was surprising and outrageous. And it’s been surprising and outrageous to virtually every single person I’ve explained it to.” Writing this profile gave me a new perspective on the history of my home city, and it helps illuminate so much of what’s behind today’s racial-justice protests. Johnson’s take on how and why anti-black racism took a unique trajectory in states west of the Mississippi River pertains to Minnesota just as it does to Missouri.

Bryan Stevenson

Screenshot by Harvard Magazine

Civil-rights lawyer Bryan Stevenson, J.D.-M.P.A.’85, LL.D. ’15, the man behind the memorial to lynching victims in Montgomery, Alabama, that opened in 2018, talks about about race and justice as no one else can. He speaks unwaveringly about the history of American racism while also bringing out his listeners’ deepest instincts for decency, humanity, and mercy. In “Fear and Anger Are the Essential Ingredients of Injustice,” read about his speech at Harvard Law School Class Day last week. “I think doing justice means that we have to fight against narratives of fear and anger,” he said then. “Fear and anger are the essential ingredients of injustice, of oppression, of inequality. Go anywhere in the world where people are being abused or mistreated, where their rights are not protected, and you’ll find people justifying those violations of rights with these narratives of fear and anger.”

Sociologist Matthew Desmond has done extraordinary work on the impact of lack of access to housing and eviction on America’s poor, a crisis that disproportionately affects African Americans and especially African-American women. Our 2014 cover story “Disrupted Lives” is a definitive profile of Desmond’s work and how he learned that “eviction is a cause, not just a condition, of poverty.” Desmond is also widely published in popular newspapers and magazines; I still think about and share his 2018 piece “Americans Want to Believe Jobs Are the Solution to Poverty. They’re Not,” from The New York Times Magazine.

~Marina Bolotnikova, Associate Editor

President Drew Faust and HLS professor Annette Gordon-Reed unveil a monument dedicated to people enslaved by law school benefactor Isaac Royall.

Photograph by Jon Chase/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

In “To Be True to Our Complicated History,” legal scholar Daniel Coquillette said of Harvard Law School’s connections to slavery: “Harvard Law School was the most important source of leaders for the Confederacy, with the exception of West Point.” Some 260 students volunteered; another 360 volunteered with the Union. The fatality rate for each group was extraordinarily high, around 25 percent. “There’s been nothing like this at Harvard Law School before or after,” he said, calling the Civil War “the most traumatic event in the history of the school.”

This portrait of Warren professor of American legal history Annette Gordon-Reed was among those defaced.

Photograph by Elizabeth Tuttle

We published this story a few years prior to the story above (yes, in 2015), about a shocking hate crime that took place in Wasserstein Hall: portraits of every black professor in the school’s history were defaced with black tape.

~Kristina DeMichele, Digital Content Strategist

More from “At Home with Harvard”

- Spring Blooms: Your guide to accessing the Arnold Arboretum as the seasons turn in Boston

- Harvard in the Movies: Our favorite stories about Harvardians on screen

- The Literary Life: Our best stories about the practice and study of literature

- Night at the Museum: Our coverage of Harvard’s rich museums and collections

- Nature Walks: Walking, running, and biking in Greater Boston’s green spaces, even while social distancing

- Supporting Local Businesses: Our extensive coverage of local restaurants and retailers, and how you can support them during this time of crisis

- Medical Breakthroughs: Our best stories going deep into the ideas and personalities that will shape the medical care of tomorrow

- Rewriting History: From race and colonization to genetics and paleohistory, our favorite stories about the people reshaping the study of history

- The Climate Crisis: Highlights from our wide-ranging coverage of the environment

- Crimson Sports Illustrated: With 2020 winter sports ending early and the spring collegiate season wiped out almost entirely, we look back at Crimson highlights from past years.

- The Real History of Women at Harvard: Stories covering the admission of women, the Harvard-Radcliffe merger, the rise of women in the faculty ranks, Harvard’s first woman president, and more

- The Undergraduate: Our favorite student essays on the undergraduate experience

- The Secret Lives of Animals: From zoology and evolutionary science to animal-rights law to the joys of local wildlife, a selection of our favorite animal stories

- Harvard on the Small Screen: Our coverage of the creators, writers, and actors in your favorite TV shows

- Extraordinary Lives: From our “Vita” section, extraordinary profiles of authors, artists, activists, and more

- Great Legal Minds: Our favorite stories on the minds reshaping American law

- Harvard History through a New Lens: Our most notable stories about episodes in Harvard’s history, some only recently fully unearthed