When poets die young, youthfulness comes to seem like the essence of their work, the thing they were born to write about. If John Keats hadn’t died at 25 of tuberculosis, he might have gone on to write great poems about marriage, parenthood, and middle age; since he never got the chance, he is forever a poet of adolescent exuberance and melancholy, of ambitions and dreams. Some of the best-loved poets in English have been doomed to eternal youth, from Thomas Chatterton in the eighteenth century to Sylvia Plath in the twentieth.

Donald Hall ’51, who died in 2018 a few months shy of 90, was one of the rare poets with the opposite destiny: he was born to write about aging and being old. The earliest poem he chose to include in The Selected Poems of Donald Hall, “My Son, My Executioner,” is about how becoming a parent brings old age closer, even for parents as young as Hall and his first wife, Kirby: “We twenty-five and twenty-two,/Who seemed to live forever,/Observe enduring life in you/And start to die together.” In one of the last poems in the book, Affirmation, Hall wrote about that journey from the other end: “To grow old is to lose everything./Aging, everybody knows it.”

Donald Hall in a 1951 yearbook photo

Photograph by Harvard Yearbook 1951

As these lines suggest, Hall wrote about age without illusions, but also without embarrassment. That makes him a rarity in American culture, where getting old is usually regarded as a faux pas, something to be staved off with diet and exercise as long as possible and then hidden with plastic surgery. Robert Browning’s once-famous invitation—“Grow old along with me!/The best is yet to be,/The last of life, for which the first was made”—would find few takers today. Hall wouldn’t necessarily have echoed Browning: he wrote too much about grief and mourning to believe that the last part of life is the best. But he had an instinctive sense that it was the part that mattered most.

So the posthumous publication of a new book by Hall titled Old Poets: Reminiscences and Opinions feels highly appropriate—especially because it’s actually an old book in a new guise. Long before Hall became an old poet himself, he was an ambitious novice besotted with old poets. In the late 1940s and 1950s, as an undergraduate at Harvard, a graduate student at Oxford, and then back at Harvard as a junior member of the Society of Fellows, Hall seized every opportunity to meet what he called the “bishops” of midcentury poetry—revered figures like T.S. Eliot ’10, A.M. ’11, Litt.D. ’47, Robert Frost, and Marianne Moore, who had once been the bomb-throwing rebels of Modernism. In 1978 Hall published a book of reminiscences of these encounters, Remembering Poets; 14 years later, he brought out a new, expanded edition under the title Their Ancient Glittering Eyes, a phrase borrowed from Yeats. It is this book that now returns in a third version as Old Poets, having grown and evolved over the decades along with its author.

The Yeats poem where Hall found that title, “Lapis Lazuli,” is about a Chinese gem carving that shows three old musicians climbing a mountain. It’s an emblem of the artist on life’s journey, and Yeats concludes by insisting that even when the art is sad, the artist is fundamentally content:

On all the tragic scene they stare.

One asks for mournful melodies;

Accomplished fingers begin to play.

Their eyes mid many wrinkles, their eyes,

Their ancient, glittering eyes, are gay.

With the poets Hall writes about, however, the gaiety of age sometimes takes grotesque forms; as he writes, he discovered that “the great were weird.” Marianne Moore, living on her own in a rapidly decaying part of Brooklyn, serves him a lunch consisting of a few raisins, a few peanuts, three saltines, and a quarter of a canned peach, each served in its own pleated paper cupcake liner. Dessert consists of a “mound of Fritos” poured from the package onto his tray: “I like Fritos,” Moore says, “They’re so nutritious.”

At the opposite pole from this homely eccentricity stands the exaggerated formality of T.S. Eliot, a Nobel Prize-winner who had been famous for decades. When Hall was invited to visit Eliot’s office at Faber & Faber, the publishing house where he worked for decades as an editor, the recent graduate was so overawed that the meeting felt like an ordeal: “I enjoyed my visit as one might enjoy…having walked a tightrope across the Crystal Palace.” On parting, Eliot ponders what advice he can give Hall as a Harvard graduate about to go to Oxford, just as Eliot himself did before World War I. Finally he delivers his wisdom: “Have you any long underwear?” Hall obediently buys a pair on the way back to his hotel, not realizing until later that Eliot was joking.

Hall wasn’t too intimidated by the great, however, to notice their all-too-human moments of vanity and competitiveness. For instance, when he praised the poetry of Wallace Stevens to Eliot, Eliot responded that he had “been keeping an eye on” Stevens as someone Faber might publish someday. The phrase implied lofty condescension, but as Hall notes, Stevens was nine years older than Eliot, and his great book Harmonium was published the year after Eliot’s masterpiece “The Waste Land.” Hall is surprised to realize that Eliot “was not being ignorant; he was being grudging.” Conversely, when Hall invited Stevens to a party thrown by the Harvard Advocate, the student literary magazine, for the visiting Eliot, Stevens declined, remarking that “he had never read Mr. Eliot much.” Even in their 70s, it seems, great poets don’t stop snubbing their rivals.

With Robert Frost, the contrast between artistic greatness and personal smallness is still more striking, even shocking. Hall was 16 years old when he first glimpsed Frost at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference in Vermont, a glimpse that was itself a revelation: “I felt light in my head and body. Merely seeing this man, merely laying startled eyes upon him, allowed me to feel enlarged.” Over years of acquaintance, however, he got to know the man inside the carefully sculpted public image, who was insecure, sarcastic, insatiably vain. Like others who knew Frost, Hall found it hard to reconcile the profound insight of poems like “Home Burial” and “Design” with the corny showman on display at Frost’s readings, where “he played the combination of Edgar Bergen and Mortimer Snerd, making himself his own dummy.”

If Old Poets only preserved Hall’s anecdotes and observations, it would be a fascinating document of literary history. But he is also a keen critic, drawing connections between the writer and his or her work. Marianne Moore’s eccentricity was obvious—everyone who met her seems to have remarked on her ever-present tricorne hat and her surprisingly thorough knowledge of the Brooklyn Dodgers. For Hall, however, Moore wasn’t just a “character.” He argues that her strangeness reflected a deep inability to understand how people ordinarily behave and why. Though Hall was writing before the term “Asperger’s syndrome” was widely known, that is exactly what he seems to be describing in Moore: her love of accumulating odd facts, the “strenuous polysyllabic precision” of her speech, combined with a lack of intuition about things like how people dress and what they serve guests for lunch.

Hall argues that this same surprising combination of attentiveness and obliviousness is what makes her poetry unique, even on the level of meter. Traditional English poetry uses accentual-syllabic meter, in which a line is defined by the number of stressed syllables it contains. In iambic pentameter, a “foot” consists of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one, with five feet to a line. Hall argues, with convincing examples, that Moore simply couldn’t hear or remember patterns of stresses, just as she didn’t seem to grasp the way people were supposed to dress or talk.

Yet she turned this seeming defect into a strength by ignoring stresses, defining her lines only by the total number of syllables. In a Moore poem, a stanza might consist of lines of 9, 4, 4, 6 and 8 syllables, with the pattern repeated in each stanza. This makes her poems look highly sculpted on the page, yet when read aloud they sound more like prose—a contrast that defines her precise yet discursive style. “Poets in their skins will never equal their poems,” Hall concludes, but one can help us understand the other.

When I first read Their Ancient Glittering Eyes as an undergraduate at Harvard in the 1990s, it was rather astonishing to think that poets I encountered in the Norton Anthology had been known in real life by someone who was, at the time, still very much a presence in the Cambridge poetry world (Hall was poetry editor of Harvard Magazine for many years). I met Hall only once, at a book signing in New York later on, when I got the chance to tell him how much I liked a certain off-rhyme he once used. (The rhyme was paradox/exacts—I think he was glad, not so much that I praised the rhyme as that I knew the lines by memory.) But Hall could often be seen in those years at the Grolier Poetry Book Shop, the bookstore on Plympton Street; dinners at the Signet Society, the undergraduate arts group; and events at the ramshackle South Street headquarters of the Advocate.

Donald Hall in October 1974

Photograph by Stephen Blos (Creative Commons)

These were all places Hall had known since he was a college student himself. During Hall’s undergraduate years at Harvard, its campus teemed with poets, including John Ashbery ’49, Litt.D. ’01 Frank O’Hara ’50, and Kenneth Koch ’48, who would go on to shape the era-defining New York School of poets and painters. “My Harvard was a paradise of poets and theater,” Hall wrote in his memoir Unpacking the Boxes. “These years were not the best of my life, heaven knows, but they were the first years of my best life. Harvard was also frightening—these folks were smart!—but my fear was more stimulating than debilitating; it was good to swim with the sharks.”

In the years he writes about in Old Poets, Hall was a poetry-world prodigy. Having decided at 14 that he would be a poet, he went on to win prizes and edit literary magazines at Harvard and Oxford, then became poetry editor of the Paris Review. The greatest poets of the day embraced him as an heir—more than one of the figures in the book called him “son.” He got a job teaching writing at the University of Michigan and seemed set for a successful career, at a time when academic success and poetic success were beginning to seem like the same thing.

But after 17 years of teaching, Hall’s path took a dramatic swerve. Following a divorce and several years of personal and creative stagnation, in 1975 he resigned his professorship and moved with his second wife, the poet Jane Kenyon, to the village of Wilmot, New Hampshire. The move was the fulfillment of two long-held dreams. First, it meant working full-time as a writer. In Old Poets, he recalls that early in his teaching career, he met the English poet Robert Graves, who made a living from his novels and journalism. When Hall confided that he wished he could do the same, Graves challenged him: “Have you ever tried?” Now he would, and in the second half of his life Hall became a prolific author of memoirs, essays, and children’s books, as well as an editor and lecturer.

Hall’s step into the future was also a return to the past. The property he and Kenyon moved into was Eagle Pond Farm, which had been in his mother’s family since the Civil War and where he had spent summers as a child. In the 1930s and 1940s, Hall writes, going from his home in suburban Connecticut to the farm in rural New Hampshire was like stepping back in time. The title character of his most popular children’s book, Ox-Cart Man, could have been one of his own ancestors—an early nineteenth-century farmer who makes everything he needs at home, bringing his produce every year to the Portsmouth Fair and selling everything down to the cart and the ox.

One reason why Hall was drawn to old poets is that he was so close to his maternal grandparents and the past they represented. “On the farm I felt myself protected by the old in a gallery of the dead. They sang that I was their own,” he writes in String Too Short to Be Saved, a collection of nostalgic sketches about those summers that was one of his most popular books. Hall writes about the “the long anthology of stories” that his grandfather told him about the place and its past: “He was giving his life to me, handing me a baton in a race, and I took his anecdotes as a loving entertainment, when all of them, even the silliest, were matters of life and death.”

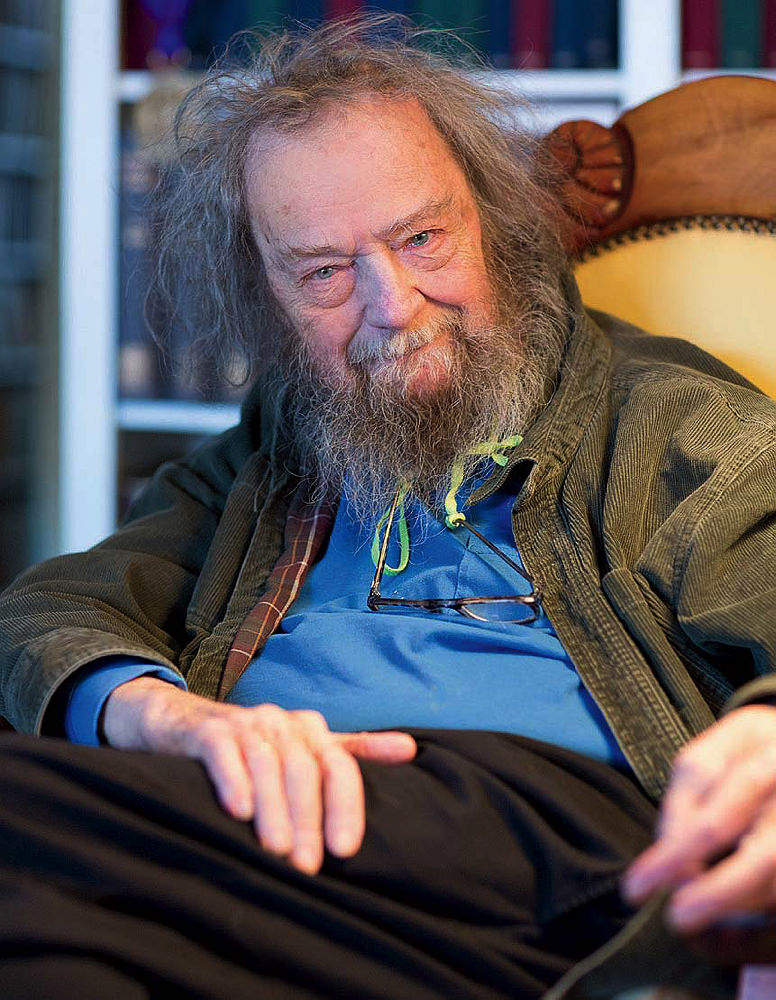

Donald Hall in old age—his last subject—as photographed in 2014

Photograph by Maundy Mitchell

Hall’s own best work in poetry and prose can be seen as forging the same kind of link between past and future. Starting with his 1978 collection Kicking the Leaves, the first book of poems he wrote at Eagle Pond Farm, he would write mainly about the passage of time, the way growing old turns the present into the past. In his poem “Maple Syrup,” Hall writes about exploring the farmhouse and finding in the cellar the last jar of syrup his grandfather stored, 25 years earlier. The poet and his wife taste “the sweetness preserved, of a dead man/in the kitchen he left/when his body slid like anyone’s into the ground,” and it’s clear that the poem is Hall’s own jar of maple syrup, meant to last when he has joined his ancestors.

Another prospect of mortality appears in the book’s title poem, “Kicking the Leaves,” where Hall remembers an afternoon in Ann Arbor, walking home from an autumn football game with his son and daughter: “their shapes grow small with distance, waving,/and I know that I/diminish, not they, as I go first/into the leaves, taking/the way they will follow, Octobers and years from now.”

It was only logical for Hall to expect that he would also “go first” before Jane Kenyon, who was 19 years younger; when they met, she was a student at Michigan and he was a middle-aged professor. But Kenyon, who became a highly regarded poet, died of leukemia in 1995 when she was just 47—a shattering loss that Hall wrote about extensively in poetry and prose. If his grandparents’ mortality, and even his own, could be bittersweet in contemplation, the reality of his wife’s death was brutally unnatural:

I lift your wasted body

Onto the commode, your arms

Looped around my neck, aiming

Your bony bottom so that

It will not bruise on a rail.

Faintly you repeat,

“Momma. Momma.”

The great Modernist poets, the ones Hall writes about in Old Poets, may be the most brilliant and powerful America ever produced, but nowhere in the work of Eliot or Moore will you find this kind of unsparing bodily reality. It took the experience of a long lifetime to turn Hall from a worshiper of art into a chronicler of life, and that very transformation may be his most important legacy.

He sums it up in the late poem “The Things,” where he writes that after decades, he no longer notices the framed pictures by famous artists that decorate his house. But he still loves to look at homely souvenirs: “a white stone perfectly round,/tiny lead models of baseball players, a cowbell/a broken great-grandmother’s rocker,/a dead dog’s toy—valueless, unforgettable detritus.” The poem ends by predicting that his children will throw these things away, just as he threw away his mother’s things when she died. But by translating them into poetry, Hall found a way to make them last.