Milman Parry saw the Homeric epics through new eyes, heard them through new ears.

The Iliad and the Odyssey, he said, were the work of generations of illiterate poets who composed orally; their poetry took wing in the moment, were reduced to print only centuries later. The demands of their poetic rhythm, thedum-diddy, dum-diddy of dactylic hexameter, ruled their word choice as much as the gods, heroes, and epic stories they depicted.

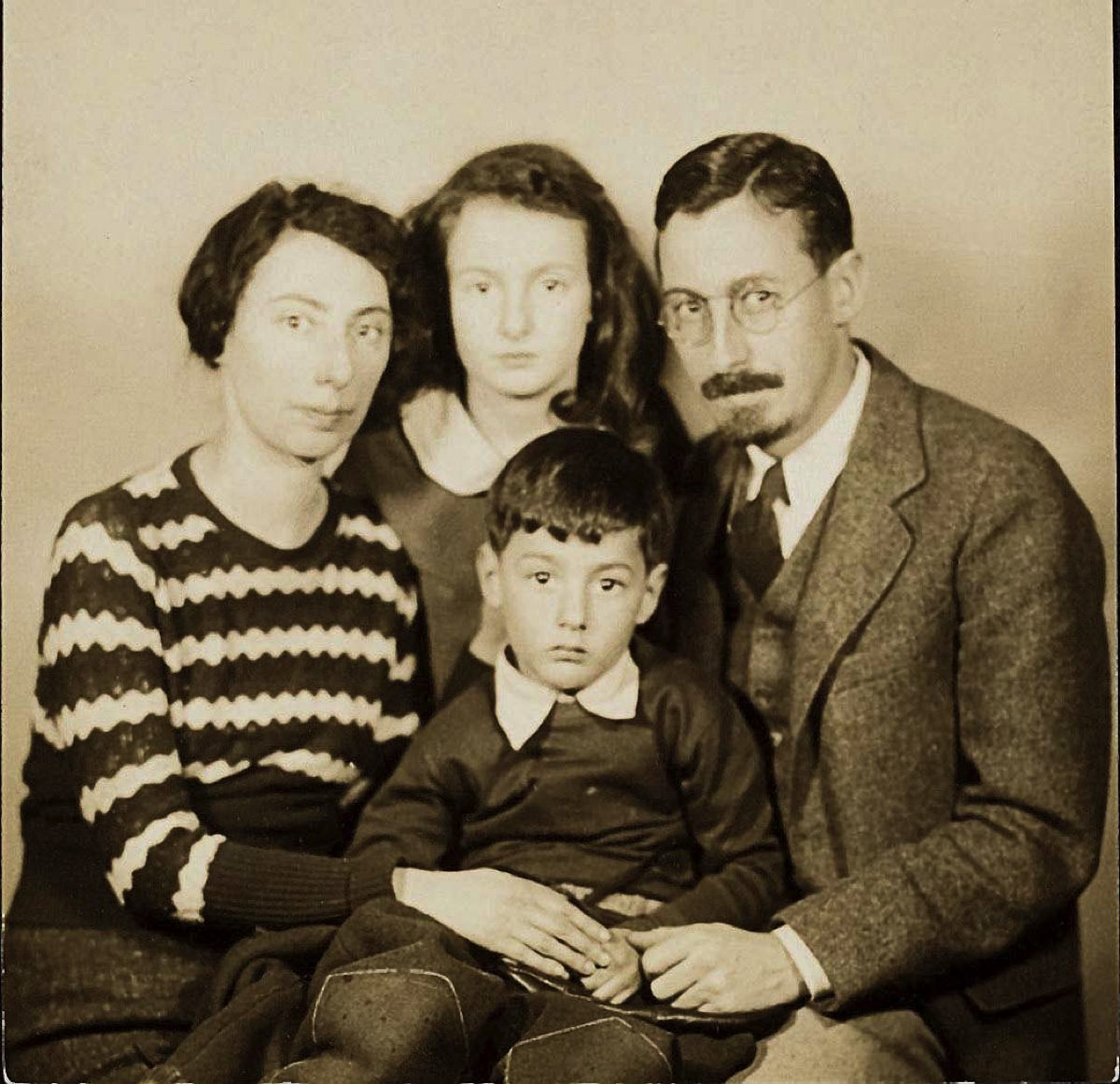

Parry and family, 1931

Photographs courtesy of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University

As a 21-year-old graduate student of Greek at the University of California at Berkeley, Parry, the son of an Oakland pharmacist and the first of his family to attend college, flirted with an early version of this idea in the summer of 1923. It became a succinct master’s thesis that soon was consigned to the library stacks and forgotten. The following year, with his wife, Marian, and their infant daughter, Parry went to Paris, worked on his French, enrolled at the Sorbonne and, under the tutelage of French scholars, refined and expanded his idea into an intricately argued doctoral thesis.

In 1928, he returned to the United States and, after a year on the faculty of a small midwestern college, took a position at Harvard, as instructor in Greek and Latin and tutor in the Division of Ancient Languages. He remained at Harvard for the rest of his brief life, which ended in 1935 with the blast of a revolver in a Los Angeles hotel room: At the time it was judged a tragic accident. Later, some would blithely ascribe it to suicide, though the evidence is lacking. Others, within Parry’s family, would see the shooting as his wife’s doing, a moment’s raging vengeance for supposed marital cruelties.

But the ideas that consumed Parry transcend the doubts surrounding his death. His doctoral thesis was a nice piece of scholarship, exhaustive and respected; yet while he’d theorized about the work of oral poets, Parry had never actually heard one speak or sing. So, at the suggestion of a judge at his thesis defense in Paris, he resolved to visit Yugoslavia, where Serbs, Montenegrins, and Bosnians still plied its villages and mountain byways with the songs and stories of their own distinct oral literature. In two trips, extending over a year and a half, Parry recorded hundreds of mostly illiterate singers who, to the rhythms of one-stringed instruments known as gusles, spun out long, larger-than-life sagas of blood, battle, revenge, grandeur, and intrigue.

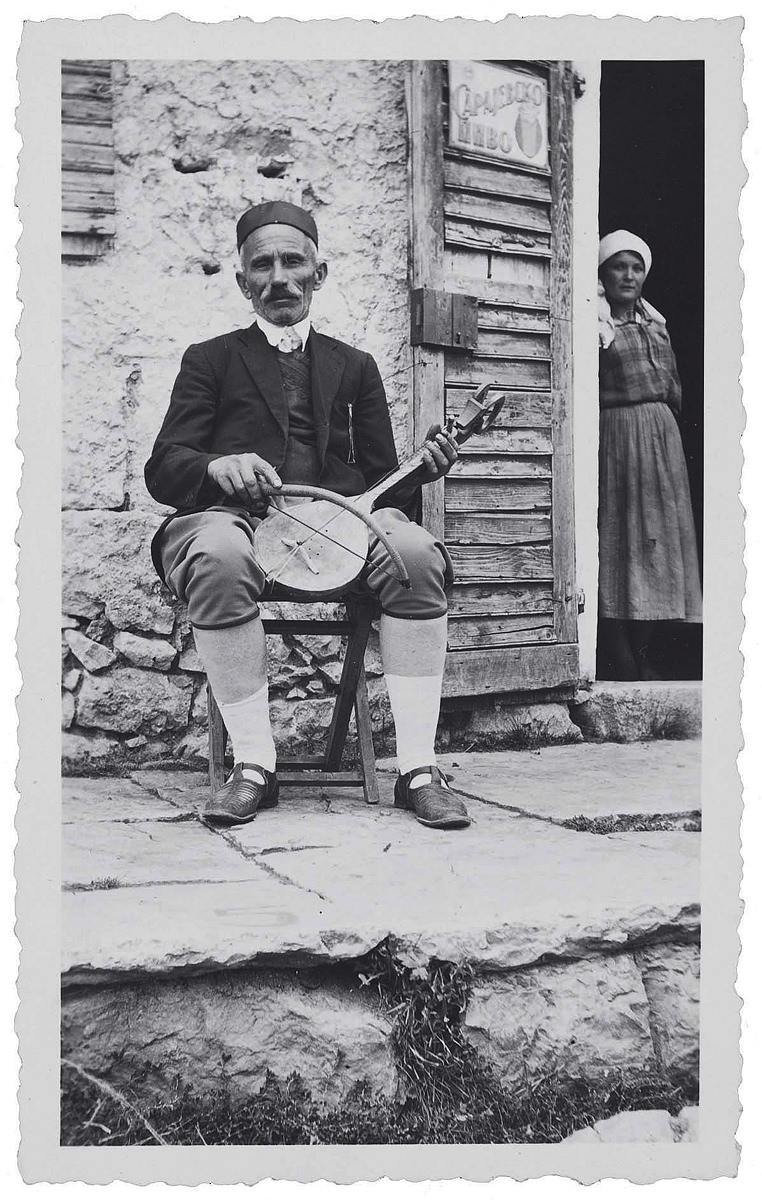

Serbian singer Todor Visnjevac playing a gusle in Gacko, Herzegovina, circa 1933-1935

Photograph courtesy of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University

Often, Parry found, they sang the same songs as other guslars did yet were never quite the same. Not sung to a written text, the story would shift course, yield to the singer’s whims, or to some urgency or impatience in his audience: This time, or next, they’d become longer and fuller, or else cropped back, introduce new characters, or new incidents, new language bubbling up in obedience to the poetic rhythms of his tradition.

Through something like this oral, not written, process, the Odyssey and the Iliad came to be, asserted Parry. And his idea pushed well beyond the merely fertile or “suggestive”; down the years, generations of Homeric scholars had done plenty of that. Parry was determined to prove it, sometimes quasi-mathematically, statistically. In the late 1920s, when he and his wife lived in a little pension in Sceaux outside Paris, Marian would remember Milman forever upstairs, hard at work, “counting all these epithets.”

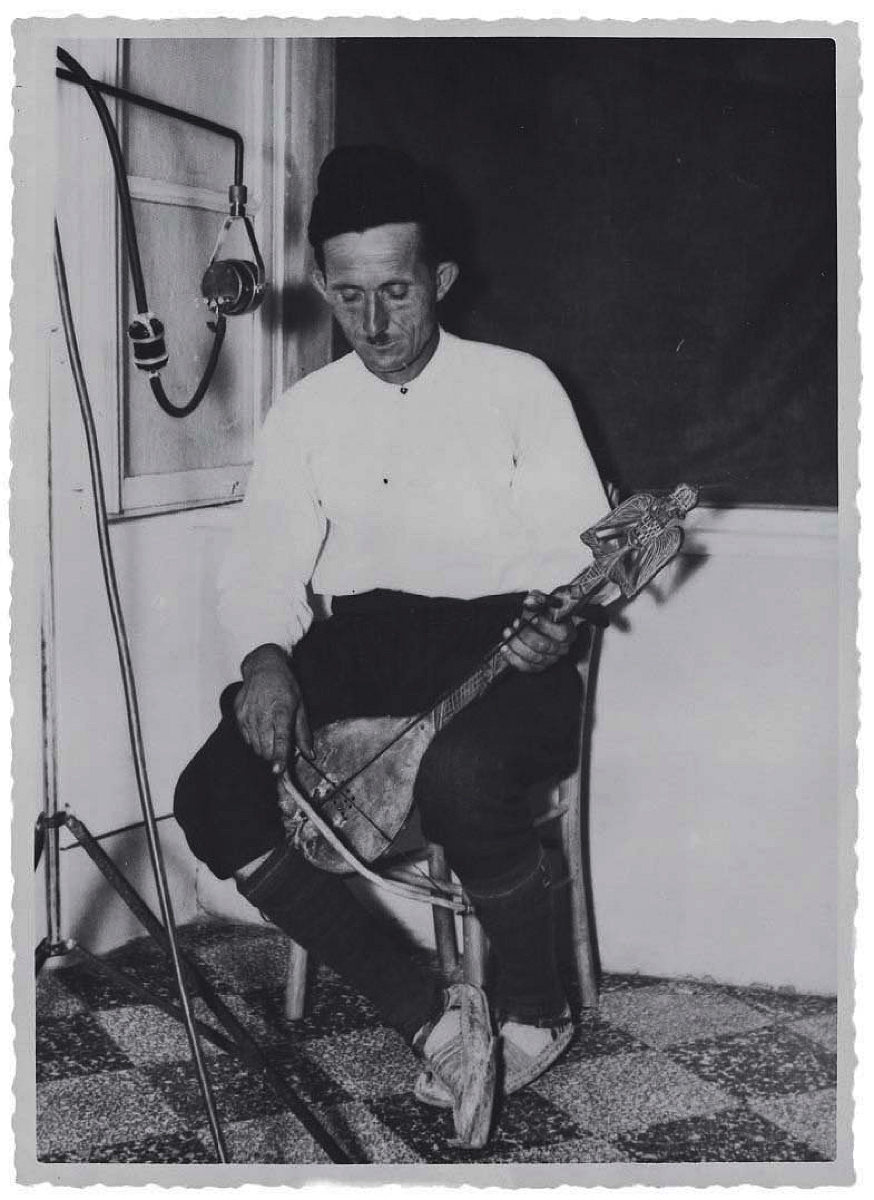

Croat singer and guslar Pero Raguz making a recording in Stolac, Bosnia and Herzegovina, circa 1933-1935.

Photographs courtesy of the Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University

The epithets were that most familiar marker of the Homeric epics, adjectives intimately joined, again and again, to gods and heroes, places and things. Like wine-dark sea, wind-quick Iris, shining Hector, grey-eyed goddess Athena. Each with its distinctive sound rhythms in the original Greek, akin to English’s stressed or unstressed syllables, they could be seized by the singer as he sang to fill a niche in the dactylic hexametric line. To generations of skeptical classicists Parry all but proved that they appeared when and where they did not to advance the story but to sweetly fill the sung line. The swift ships of one common epithet, wrote Parry, were swift “even when drawn up on land.”

Dead at age 33, Parry may not have made the impact he did but for Albert Lord, ’34, Ph. D. ’49, his assistant on his second trip to Yugoslavia. A recent Harvard grad, young Lord was not Parry’s “colleague”; he helped set up the recording equipment, kept track of the songs, collected the aluminum disks on which they were saved. But after Parry’s death, Lord felt the awful weight of his mentor’s work. He went on to a Harvard Ph. D., and a quarter-century later published his own magnum opus, Singer of Tales, which enriched and deepened oral poetry beyond all Parry had begun.

The years have brought challenge and reinterpretation to Parry’s big idea, but it rests largely secure. Shakespeare wrote Macbeth. Virgil wrote the Aeneid. But if Homer may yet be called author of the Odyssey, he did not write it as they did; after Parry, we understand better today, there are different ways to “write.”