In early February, non-tenure-track faculty and other academic staff members launched an effort to form a union, calling for higher wages, better job security, and stronger workplace protections regarding issues like safety and harassment. “We’re fighting for a seat at the table,” Thomas Dichter ’08, a lecturer in the history and literature department and a staff member at Harvard Medical School (HMS), said during one of two union rallies February 14, in Harvard Yard and at the Longwood campus. “We are done with decisions being made over our heads in rooms that we have no access to.”

According to organizers, the Harvard Academic Workers-United Auto Workers (HAW-UAW) seeks to represent up to 6,000 University employees, a group that includes lecturers, preceptors, postdoctoral fellows, instructors, teaching assistants, researchers, and adjunct faculty members. Some of those positions operate on short-term contracts that must be renewed annually; in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), for example, non-tenure-track faculty members can hold teaching appointments for a maximum of eight years. After that, they are ineligible for renewal.

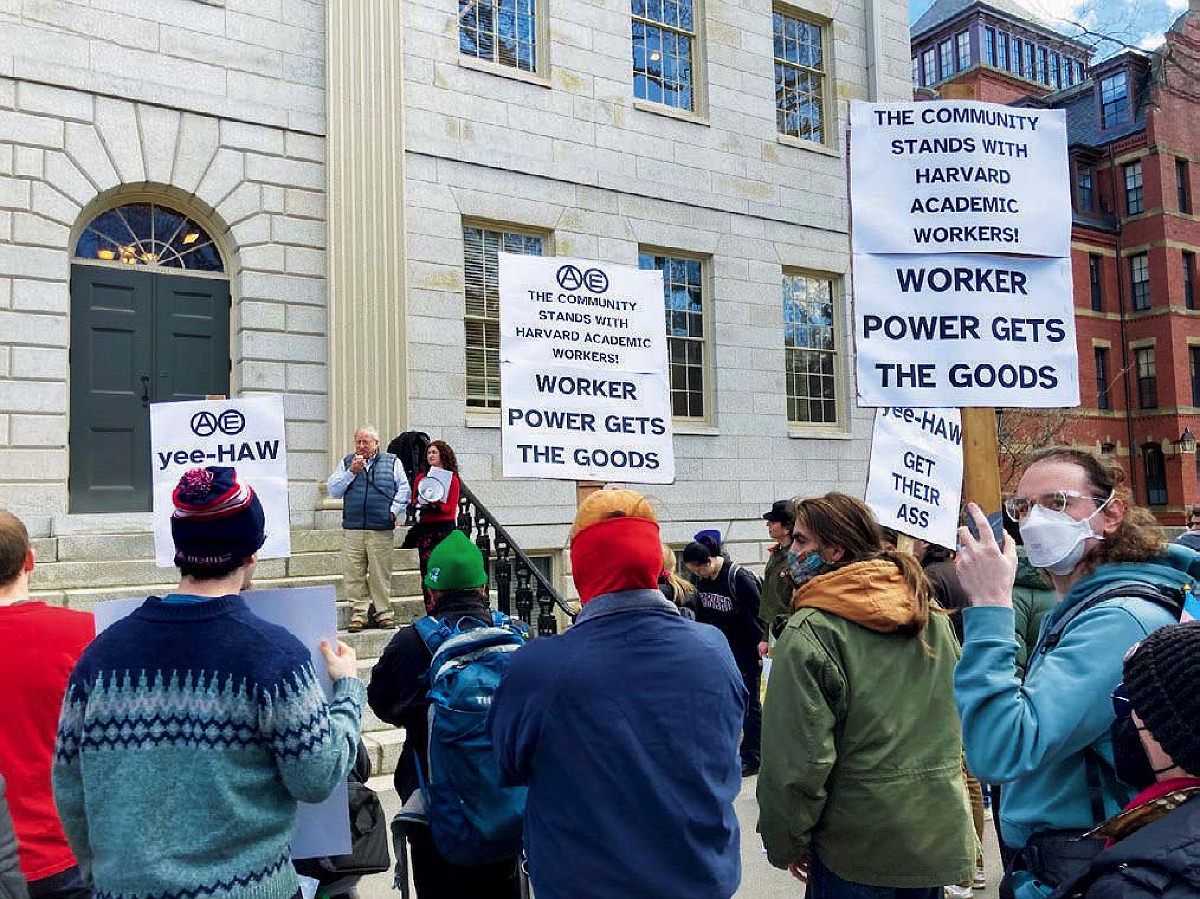

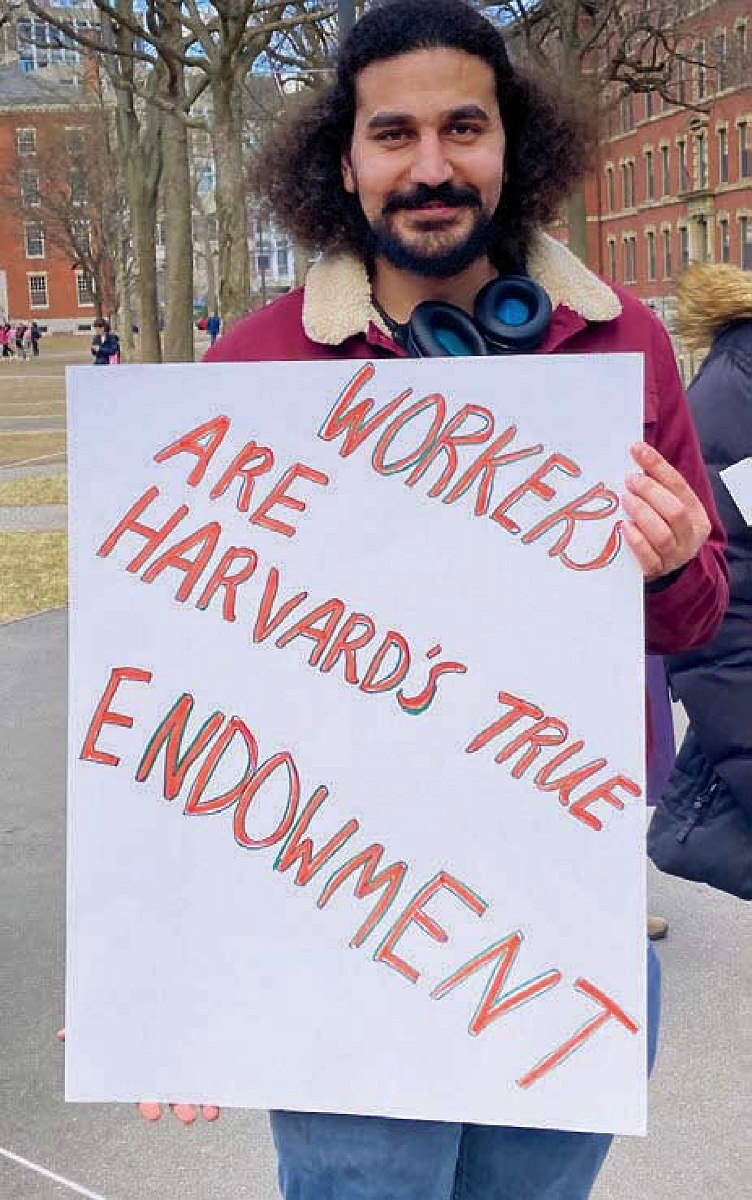

Organizers advocating a union of non-tenure-track workers rallied in Harvard Yard in February.

Photograph by Lydialyle Gibson

This precarity is a central theme for organizers. Michaela Thompson, an environmental historian and Harvard Extension School instructor, was a preceptor in environmental science and public policy until last June, when she reached the eight-year threshold. “Harvard has called this wheel of disposal a virtuous cycle,” she told rallygoers in the Yard, “while positions sit unfilled and workers are jettisoned.” Yiddish preceptor Sara Feldman described how term limits disrupt students. “Our working conditions are their learning conditions,” she said, “and when non-tenured faculty lose their jobs, students lose the faculty who know them best.”

The limit for non-tenure-track teaching staff has long been a subject of discussion within FAS. In 2009, the FAS Advisory Committee on Non-Ladder Appointments wrestled with the question of whether a career track should be created for non-tenure-track faculty members. In the end, they decided no. In the report, the committee reasoned that “Many of the teaching functions held by non-ladder faculty are highly demanding and require regeneration that brings in fresh ideas, new talent, and the most recent pedagogical techniques.” The committee also concluded that, if too many non-ladder positions were made permanent, their ranks would become “top-heavy,” and “the flow of new talent would become a trickle.”

Organizers argue that, as universities, including Harvard, increasingly depend on non-tenure-track faculty members to carry the teaching load, these jobs no longer function as the transitional positions they once were. Fifty years ago, nearly 80 percent of U.S. college instructors were tenured or tenure-track; today, that proportion has essentially flipped: more than 70 percent are not in line for tenure. Within the FAS, the 2021-2022 annual report on faculty trends showed that while the ladder-faculty population has barely grown since 2010, the number of non-ladder faculty members has risen by 44 percent.

Organizers advocating a union of non-tenure-track workers rallied in Harvard Yard in February.

Photograph by Lydialyle Gibson

“Folks are spending longer in these situations,” Boston city councilor Kenzie Bok ’11—a social studies preceptor from 2017-2021—said at the Longwood rally. Ben Ewen-Campen, Ph.D. ’14, an HMS genetics postdoc and president of Somerville’s city council, said that career pathways have similarly shifted for non-tenure-track researchers. “There are people here for multiple years, during prime earning years of their life, with families, with kids, trying to pay for housing and child care in one of the most expensive cities in the country.”

Compensation is one of the most pressing issues motivating the unionization push, which comes at a time of inflation, prohibitive child-care costs, and steeply rising housing prices in one of the most expensive real-estate markets in the country. HAW-UAW organizers said that many non-tenure-track employees make as little as $50,000 per year.

In light of these concerns, Harvard’s $50-billion endowment and yearly surpluses looms large. In its most recent financial report, released last June, the University recorded an operating surplus of $406 million for fiscal 2022, up from $283 million the previous fiscal year. Harvard has operated in the black since fiscal 2014 and produced nine-digit surpluses annually since 2017.

This organizing effort also comes at a moment of economic tension between the University and its largest unionized cohort. Since April 2022, Harvard has been in difficult negotiations with the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers (HUCTW) over compensation and benefits. In November, unable to reach an agreement on wage increases, the two sides began working with a third-party mediator.

HAW-UAW organizers are now collecting signatures on union authorization cards in hopes of prompting the University to voluntarily recognize the organization; otherwise, if 30 percent of eligible union members sign authorization cards, then union organizers can petition the National Labor Relations Board for a formal election, in which a majority vote would be required to certify the union. There is recent precedent for their plan: the UAW-affiliated Harvard Graduate Students Union began organizing in September 2015, won a unionization vote in May 2018, and ratified an initial contract in June 2020.

Read more about the current organizing effort at harvardmag.com/workers-rally-23; for background on the Graduate Student Union, see harvardmag.com/union-18.