“You have to get the eyes right,” says portrait artist Nina Skov Jensen ’25. “You can mess up a lot of other things and it won’t matter, but the eyes have to be right.”

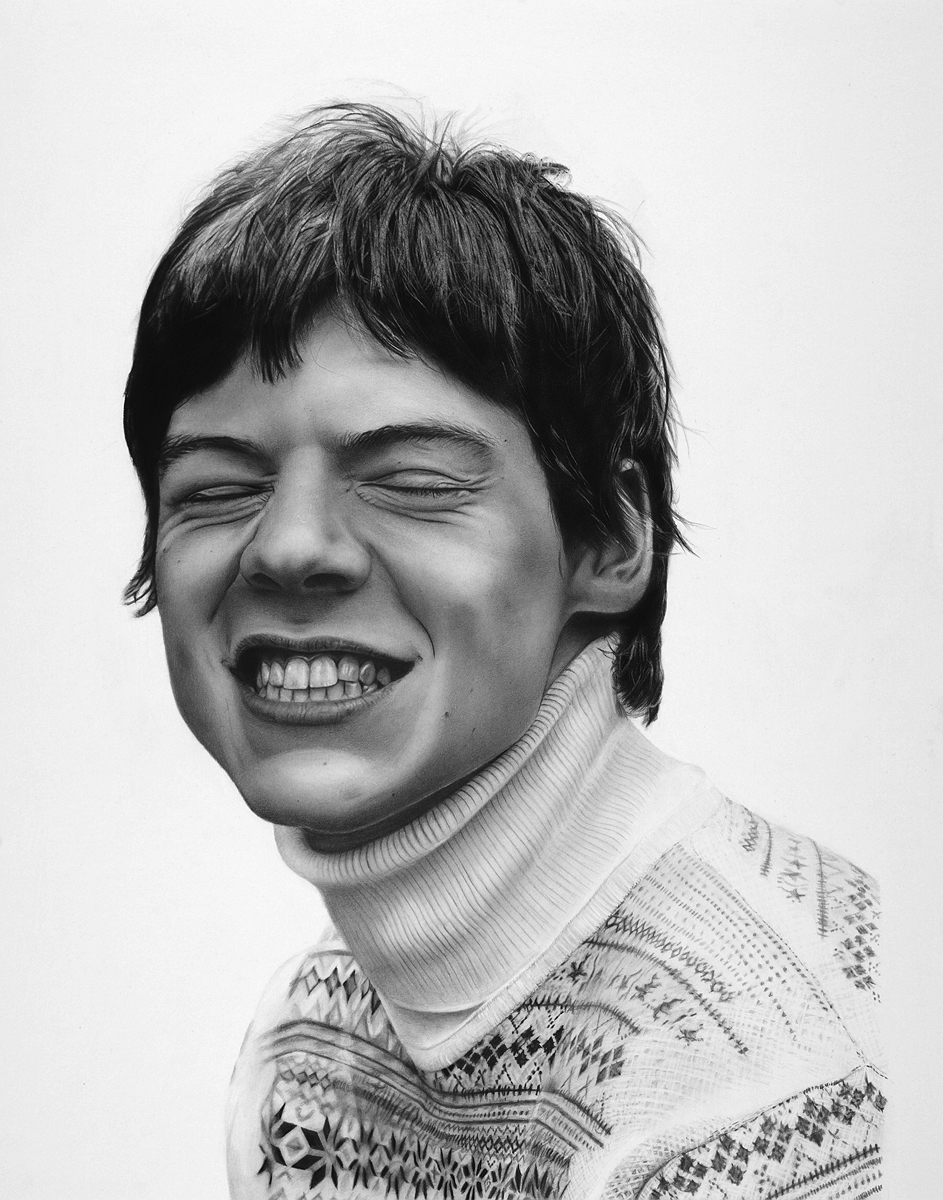

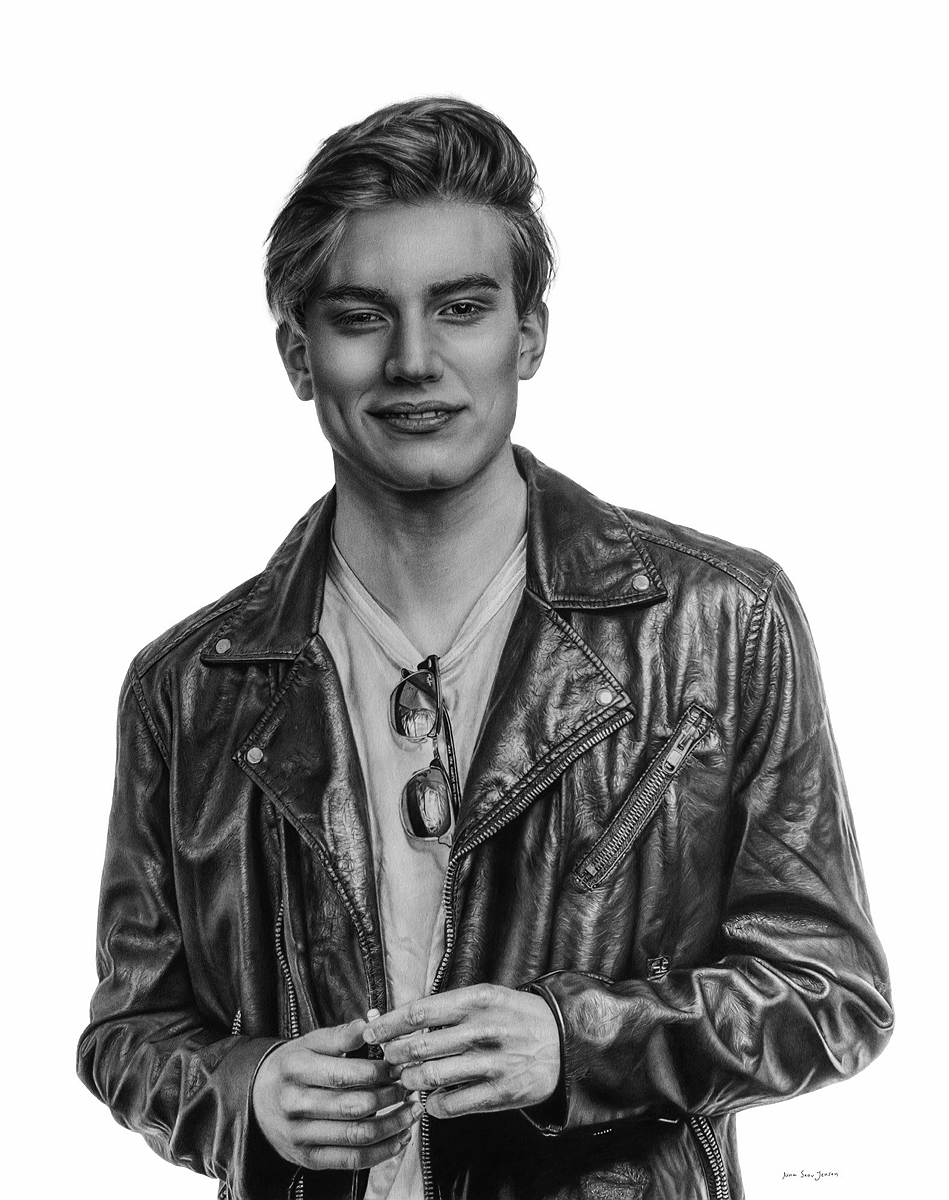

That was one of the first lessons Jensen absorbed when she began teaching herself to draw, as a 12-year-old growing up in Denmark. Equipped with a sketchbook, a set of pencils, and a fascination with celebrities, she would study images of famous faces on social media—Beyoncé, Adele, Robert Downey Jr., Harry Styles—and then try to recreate them. Now, nearly a decade later, she is a professional artist whose portfolio includes portraits of Danish government officials and members of the monarchy. Her work has been shown in galleries in the United States and her home country.

But Jensen’s trajectory hasn’t only pointed upward, and recently she’s had to teach herself much more than drawing and painting: after a severe health condition forced her to take a leave from the College two years ago, she has been learning a lot about who she is and who she wants to be, about what it might mean to live a full life, and about the relationship between happiness and ambition. “Especially at a place like Harvard, we have a tendency to just power through life, pushing for the next thing—and then the next thing and the next thing,” she says. “We have these goals, and we achieve them, and then it’s like, ‘What now?’ After five minutes of contentment, you get this empty feeling.…These reflections have changed a lot of my mindset around how I want to exist, and how I want to interact with other people.”

Jensen chose Harvard for many of the same reasons that undergraduates often do. “It was a dream I had,” she says: a place where she could study seemingly anything, and that afterward could help her achieve whatever she might strive for. By the time she arrived on campus in fall 2021, she had already established herself as a serious and self-confident artist. At 13, she progressed from posting stunningly lifelike sketches of celebrities on social media to traveling to film premieres in London, where she would wait outside of venues to get the stars’ autographs and show them her work. On one of those trips, a chance encounter on the sidewalk with art collector Beth Rudin DeWoody led to gallery shows of Jensen’s work and a handful of new commissions. In high school, she expanded into oil painting and earned what remains her most illustrious commission, a portrait of Princess Marie of Denmark. She describes the experience of creating that work as “kind of a fairy tale.” In the painting, the princess wears a simple white suit and a knowing smile, hair loose at her shoulders, hands folded at her waist. She gazes out from the canvas expectantly, almost as if waiting for the viewer to speak.

Entering Harvard, Jensen had another pursuit in mind as well: advocating for people who, like her, are autistic. She was diagnosed with the condition as a child, at about the same time she became interested in art, and not long after her older brother found out he had autism—and just before her mother’s diagnosis. “I’m really lucky, because [being autistic] was always normal for me,” Jensen says. “I had a supportive family—my mom is amazing—and I went to a school where people had diagnoses. So, I never felt alienated.”

Instead, she believes, autism contributed to her artwork: her ability to learn quickly, her commitment to endless trial and error, her obsessive attention to detail. Many of Jensen’s paintings and drawings look practically photographic, so true to life that they seem almost in motion. (Her diagnosis also provided an initial introduction to Princess Marie, who serves as patron of the Danish Association for Autism.) At Harvard, she’d planned to launch a student organization devoted to expanding opportunities for autistic students, and she embarked on a government concentration, with an eye toward a potential career in autism-related activism and policy.

But then everything unraveled. During the second semester of her freshman year, she developed POTS (postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome), a condition in which the heart beats faster than normal, causing palpitations, nerve pain, and other symptoms. POTS can make ordinary activities—a long walk, a deep conversation, a day at the easel—feel exhausting. The condition has been associated with COVID-19 and, to a lesser degree, with the COVID-19 vaccine; Jensen says that, in her case, the vaccine was the precipitating factor. She left campus in spring 2022 and has been recovering at home in Denmark. It’s been an “uphill battle,” she says, but she’s much better and hopes to return to Harvard this coming school year.

In the meantime, she’s maintained ties to campus where possible. Last fall she audited a statistics course; she and a College friend had begun teaching each other Spanish, and they’ve kept talking. She has also stayed in touch with Matt Saunders, professor of art, film, and visual studies, whose course “Painting’s Doubt” she took (but didn’t finish) in 2022. It asked students to explore how “hands-on art-making,” according to the course description, “lead[s] us to perceive, represent, and inhabit our world differently”—a question that now speaks to Jensen more urgently than ever. Corresponding with Saunders from her home 30 minutes outside of Copenhagen, she’s continued learning from him informally, working to hone her technique. Last November, she finished a portrait that had consumed a year’s worth of work, depicting Sophie Haerstorp Anderson, Lord Mayor of Copenhagen: dressed in a suit of deep, warm blue, she stands framed by a geometric red-and-gray background, her pose powerful, a delicate gold bracelet dangling at her wrist.

Jensen looks forward to resuming her formal artistic studies, and she’s as set as ever, she says, on a concentration in government. She’s motivated partly by her dedication to autism issues but also by her experience of being sick. Much of her recovery has involved learning how to better regulate her nervous system so that normal exertion doesn’t overwhelm her; the effort has been painstaking but transformative, she says, and she’s interested in working with organizations that help others with dysregulated nervous systems, which some studies have shown can contribute to chronic conditions like hers, as well as other health problems such as anxiety, depression, and metabolic abnormalities. Recalling her freshman year, she says, “My nervous system was completely shot that first semester. I did well academically, but I just had no grasp on what was important for me….And there are so many people like that, at Harvard and other places.”

That revelation is partly why she now also lingers on memories of Harvard activities that may have seemed ancillary at the time, like joining the Krav Maga Club and learning the Israeli martial art. She took a class called “Archaeology of Inequality,” examining how the remains of past societies reveal layers of inequality—or its opposite. The course so fascinated Jensen that she’s considering a second concentration in archaeology. “I’m more about pursuing my interests now than getting a specific job or a specific accomplishment,” she says. “Just focusing on finding happiness and maybe helping other people feel a little bit better. That’s the kind of thing you realize when you lose everything that you know.”

Throughout her recovery, her artwork has sustained her, helping Jensen keep a sense of buoyancy, which remains striking even now, as she speaks via video chat from her parents’ home on a gray midwinter evening in Denmark. She describes how her experiences have begun to shape her artwork: she’s developing an idea for a new portrait—but an imagined one—of a woman standing in a puddle, holding a balloon, drenched despite her yellow raincoat and boots, wet hair blown back by the wind. “It’s a lot about feeling unwell,” Jensen says, but the idea is larger than that. She envisions a romanticized landscape in the background, perhaps something incongruously sunny and bright. It’s an image, she says, of fragility and strength, both ominous and optimistic, filled with the kind of poise and self-assurance that, in spite of everything, Jensen still exudes.