One by one, in the course of a decade, the masterpieces emerged, each as brilliant as the last—intricately detailed nature paintings as idiosyncratic and complex as any the world has ever seen. Ducks plunge from icy branches into a winter pond. Schools of sweetfish dart between the submerged roots and stems of lotus flowers. Roosters, a recurrent obsession, flare their combs in front of brilliant hydrangeas and shady palms alike. Small blue birds perch on the slender limbs of a reddening autumn maple. Thirty such paintings of inimitable craft and artistic passion ultimately coalesced into the Colorful Realm of Living Beings, an ensemble that forms the crowning achievement of the eighteenth-century Japanese painter Itō Jakuchū.

Jakuchū (known not by his surname, Itō, but rather by his artistic sobriquet) is not a name that many people outside Japan would recognize. But Yukio Lippit, professor of history of art and architecture, says, "Jakuchū is probably the most recognized premodern artist in Japan." Lippit, who specializes in Japanese art and architecture (see "Works and Woods," September-October 2008, page 44), is curator of the exhibition Colorful Realm: Japanese Bird-and-Flower Paintings by Itō Jakuchū (1716–1800), on display from March 30 to April 29 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., as part of the centennial celebration of the Cherry Blossom Festival. (Visit www.nga.gov/exhibitions/Jakuchūuinfo.shtm for more details.) A product of several years of planning between the National Gallery and the Imperial Household Agency of Japan, the exhibition will present Jakuchū 's complete series outside Japan for the first time, along with the Buddhist triptych that accompanied it in its original home at Shōkokuji Monastery in Kyōto.

Jakuchū was born into a prominent family of grocers who ran a large wholesale market in downtown Kyōto. As head of his family, following the death of his father, his business prospered to such an extent that he was able to retire at the age of 40 and, already an accomplished artist, devote himself to painting full-time—which proved important for establishing his artistic legitimacy. "There was no higher form of praise in the sphere of the literati," says Lippit, "than to describe someone in terms that marked him as a lofty amateur,"—someone who "practices an art not for profit or commercial transaction, but who paints purely as a form of expression of interiority, for oneself or one's friends, and who paints as a kind of spiritual vocation."

That sense of spiritual discovery was also important to Jakuchū's development. In his thirties, he began to practice Zen Buddhism under the guidance of a well-known monk named Daiten, who was not only a spiritual leader, but also a respected intellectual active as a poet, a writer, and even a diplomat. Daiten introduced Jakuchū to the intellectual and cultural elite of Kyōto, from whom the merchant-artist gained extensive knowledge of the artistic and literary traditions of East Asia. Daiten in time became the abbot of Shōkokuji Monastery, with which Jakuchū himself became closely linked, producing several major projects as gifts for the temple.

But nothing that Jakuchū had previously done approached the complexity or ambition of the Colorful Realm. He began the series in 1757 and worked on it continuously until 1766, at an average pace of three paintings per year. Given the detail and technical sophistication of the paintings, this rate is remarkable. These are not the abbreviated, spare ink paintings that so many amateurs pursued, Lippit remarks, but "very highly crafted, polychrome works on silk that meticulously depict their subjects using expensive materials and laboriously executed techniques that are associated, if anything, with professional painters." Each painting is quite large—on average, about four and a half feet tall by two and a half feet wide. In addition, Jakuchū frequently employed a technique called verso coloration, which involved painting both the front and the back of a silk scroll, allowing the pigment on the back to subtly highlight the tones on the front through the weave of the silk.

Lippit believes that Jakuchū initially planned the first paintings as either individual works or a smaller set, only later expanding his vision. "At some point, under the influence of Daiten, Jakuchū began to conceive of the series as a grand backdrop for a very important ritual at Shōkokuji, and he began to adjust the scrolls of the Colorful Realm accordingly," he explains. The early paintings hew closely to the conventions of a major East Asian genre known as bird-and-flower painting, but later works become more experimental in their subject matter and treatment for reasons closely tied to an important Buddhist ceremony called the Kannon repentance ritual.

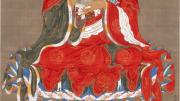

The ceremony—performed annually at Shōkokuji—describes the appearance of the Bodhisattva, or enlightened spiritual guide, Kannon in 33 different manifestations that he assumes in order to accommodate the various spiritual stages of advancement of different believers. There are only 30 paintings in the Colorful Realm, but Jakuchū complemented it with a triptych featuring Śākyamuni, the historical Buddha, flanked by two Bodhisattvas, Mañjuśrī and Samantabhadra, for a total of 33. "What's interesting about the Colorful Realm is that when it's displayed in situ, the main Buddhist triptych is actually not the Bodhisattva Kannon, but Śākyamuni," Lippit notes. "That's because the chapter in the Lotus Sutra that describes the 33 manifestations of the Bodhisattva Kannon is actually being explained in a sermon by the Buddha—so the Colorful Realm creates a mise en scène of a lecture by the Buddha himself, to which all the birds and the animals are congregating in a Noah's Ark-like summons."

It's this conjunction of both the triptych and the Colorful Realm in an approximation of their original arrangement that makes the National Gallery exhibit so exceptional, he adds: "It will combine, for only the second time in over 100 years, all 30 scrolls with the Buddhist triptych in the center, so that you really experience the scenography of Jakuchū's entire set." Shōkokuji gave the paintings to the Japanese Imperial Household in 1889 in return for funding for the preservation of the monastery, and the Colorful Realm has made occasional public appearances since then. But even the home of the series—the Sannomaru Shōzōkan, the Museum of the Imperial Collections, in Tokyo—does not exhibit the paintings all the time, and never with the accompanying triptych, as it would have been originally displayed at Shōkokuji. "All of our Japanese partners," Lippit says—the list includes the Imperial Household Agency, the Japanese embassy, and Shōkokuji itself—"really wanted to participate in this celebration of the Cherry Blossom Festival, and of long-standing historical ties between Japan and the United States."

Dodge Thompson, M.B.A. '80, chief of exhibitions at the National Gallery, observes that Lippit himself played crucial roles in bringing the Jakuchū exhibit into existence. "Yukio is the consummate diplomat. He is exceptionally thoughtful, a world-class listener, and very respectful of other people's opinions…. At every level, Yukio was involved in discussions." Thompson invited Lippit, a Mellon Fellow at the gallery from 2002 to 2003, to guest curate the exhibition at the suggestion of Yoshiaki Shimizu '63, Marquand professor of art and archaeology at Princeton, who is Lippit's mentor. The gallery often needs guest curators when showing art from outside Europe and the Americas, and Lippit was, in Thompson's words, "exceptionally well qualified for this project because he has a rich understanding of pedagogical and scientific developments in modern Japan, including a botanical and horticultural awareness—and, of course, knows a lot about the work of Itō Jakuchū."

But Lippit highlights the exceptional dedication and commitment of the many Japanese institutions involved in mounting the exhibition as the truly indispensable element in making the project work—particularly in the wake of the March 11, 2011, tsunami that devastated Japan. "Many of us involved in the show thought there was a real possibility that it might be canceled," he remembers. "But after a little bit of a pause, our Japanese colleagues expressed a desire to go forward—they really wanted this to happen more than ever. So I think it's important to note that the exhibition will take place just after the first anniversary of the disaster in Japan, and it's a very moving thing to work with people such as my counterpart at the Imperial Household Agency, Ms. Aya Ota, and others as they are dealing with the aftermath of the disaster."

The Colorful Realm loan is a remarkable artistic event, on the scale of assembling all extant Vermeers or all Monet's paintings of water lilies in one gallery, and its presence will give the Cherry Blossom Festival an added poignancy this year. "This exhibition exemplifies our strong friendship. We Japanese are so grateful to Americans for showing solidarity and friendship with us after the Great Earthquake of March 11," stated the Japanese ambassador, Ichiro Fujisaki, in a press release from the National Gallery. Lippit explains, "These are widely considered to be the most important and remarkable bird-and-flower paintings in the history of Japan, and possibly all of East Asia. The Colorful Realm went from being a kind of monastic treasure to an imperial treasure, and has become a tremendous ambassador of Japan's 'culture of nature' in the present moment."