The earliest United States trade with China, it may be hard to remember, began just after independence from Great Britain. It initially involved such goods as tea and textiles, and amounted to tens of thousands of dollars, rather than trillions. The addictive good of the era, shamefully, was opium (a major component of Chinese imports), rather than the torrent of Apple consumer gadgets flowing outward today. Unlike the great European joint-stock enterprises—the Dutch East India Company and its British counterpart—the American traders were New England entrepreneurs who set up private firms or merchant syndicates.

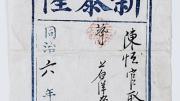

A Chronicle of the China Trade, an elegant exhibit at Baker Library drawing on Harvard Business School’s historical collections (through November 17, and online at www.library.hbs.edu/hc/heard), documents this commerce through the remarkable records of Augustine Heard & Co., from 1840 through 1877 (just one of the library’s collections of such materials). The documentary evidence, complemented by American artifacts and materials on loan from Hong Kong and Shanghai, details the growth of the family business and the swelling volume of cotton, silk, porcelain, and other goods crossing the ocean. It explores rapid institutional change, from the Chinese system of limiting trading to licensed hong monopolies under imperial control, to the forced opening of so-called treaty ports (after the Opium Wars) and the rise of compradors who managed business as trading-house employees. It follows the spread of business from coastal enclaves into China’s interior (a pattern repeated during the past three decades); the physical and social evolution of trade communities; the deployment of game-changing, speedy new technologies (clippers and steamships, antecedents to the modern cargo jet, and the telegraph); and the lubricating effects of new banking services, credit instruments—even (tea) crop futures. And yes, fortunes were made (and lost)—not only by the Heard enterprise but also by Chinese traders who proved utterly adept at business.

![Image courtesy of the Ipswich Museum Aymon. "Les quatres fils" [The Four Heard Brothers.]](/sites/default/files/styles/16_9_180x101/public/img/article/0812/jhj-ct-brothers019sm.jpg.jpeg?itok=-btX7nUO)