The novel coronavirus had a powerful downsizing effect on Harvard’s gala week culminating in the formal Commencement rituals—the 369th iteration of which will be rescheduled. There was no Baccalaureate. ROTC commissioning ceremonies were, for the nonce, conducted virtually. Reunion symposiums were replaced with a series of online conversations with University leaders and a couple of faculty luminaries. And the main event—the traditional Morning Exercises in Tercentenary Theatre, brilliantly festooned with banners—obviously could not be held safely. The 32,000 or so excited students and proud family celebrants who would ordinarily queue up by the dawn’s early light and then throng Tercentenary Theatre were dispersed worldwide, and so the proceedings, dubbed “Honoring the Harvard Class of 2020” (read the program here) were reduced for convenient viewing on the screens of smartphones (which would, under ordinary circumstances, be used to capture zillions of selfies).

Nonetheless, the show, very much modified, did go on. University president Lawrence S. Bacow spoke (more than he usually would during the Morning Exercises, in fact)—setting the tone for this most unusual event, and summoning the new Harvard graduates to engage in hard work “to perfect this imperfect world that we inhabit” (see below). So did the intended afternoon honorary guest speaker, Washington Post executive editor Martin (Marty) Baron, who addressed “subjects that I believe are of real urgency”: a very Veritas-compatible consideration of “the need for a commitment to facts and to truth” in support not only of democracy but also as “matters of life and death” amid the pandemic (see below). Two of the traditional three student orators held forth—albeit with fewer nerves to overcome than when belting it out, live, in front of the aforesaid 32,000 closest friends and guests. (Latin Salutatorian Caroline S. Engelmayer ’20 is being held in reserve, for whenever an on-campus ceremony can be held—presumably the Latin-to-English humor and aperçus will work better live.) There were affecting musical interludes. And the students who had earned their spurs—remotely, by Zoom, since March 23, and by submitting theses in PDF form—were duly rewarded by the conferral of degrees.

Like everything else this spring, a whole lot of improvising went into pulling the production off. Harvard innovativeness came to the fore—and the mixed emotions that animated the planners and participants melded with the spirit of graduations everywhere to yield a very good result for viewers dispersed around the planet.

The Preliminaries: Honors and the Would-Have-Been Reunions

The Phi Beta Kappa Literary Exercises, the starting point of the festivities in most years (and, with poet and orator, often their intellectual highlight) were canceled. But the annual PBK teaching awards, from nominations by the accomplished undergraduates themselves, were conferred, on:

- Rachelle Gaudet, professor of molecular and cellular biology;

- Edward J. Hall, Vuilleumier professor of philosophy, cited for his course “Reclaiming Argument” (which he also forcefully embodied throughout the year as the lead faculty proponent of divesting investments in fossil-fuel production from Harvard’s endowment); and

- Leah Jane Whittington, professor of English (whose Commencement experience includes serving as Latin Salutatorian in the wet 2002 festival rites).

Absent physical reunions, the University and Harvard Alumni Association organized “reunions at home,” with virtual sessions featuring President Bacow (in conversation moderated by Corporation member and forty-fifth reunioner Karen Gordon Mills ’75, M.B.A. ’77—on Zoom at the warm and cuddly meeting ID of 982 9770 1674, and livestreamed on YouTube); College dean Rakesh Khurana; Faculty of Arts and Sciences dean Claudine Gay (each of whom typically speaks at the major College reunions); plus faculty experts Alyssa Goodman, Wilson professor of applied astronomy (on the high-risk proposition, these days, of “predicting the future”); and Nicholas Burns, Goodman Family professor of the practice of diplomacy and international relations (on “promoting a more effective global response” to the pandemic—which would presumably make Goodman’s task far easier).

The would-be reunioners had plenty planned, and plenty to think about.

Connecting current alumnae and alumni deeply to the University’s past and Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “long winding train reaching back into eternity”—as the traditional parade unfortunately will not this year—class of 1970 Radcliffe secretary and report co-chair Peggy Mais Padnos wrote of graduation, then on June 11, 1970 (and the first to include both Radcliffe and Harvard seniors), “I wonder how many of us gave much, if any, thought to the class of 1920, celebrating their Fiftieth Reunion that day. Perhaps, with Vietnam very much in the news, a few thoughtful history concentrators may have connected the class of ’20 to the Great War and its horrific losses, but I wonder. That said, I hardly need to remind classmates that we came of age during a critical moment in U.S. history and that we will celebrate our college milestone at an even more perilous and uncertain time for the country.”

For the class of 1985 thirty-fifth anniversary report, class secretary Mary Warren compiled an impish list of undergraduate life way back then, featuring the then-term bill of $9,500; the “crater” in Harvard Square (now the MBTA Red Line station); landlines and pay phones; record players; and—most inconceivable of all—“We wrote letters to our families and friends,” and parents could not text back.

In the reunion committee report to the Harvard and Radcliffe class of 1995, whose twenty-fifth this was to be, one and all were invited (when the report was written) to come back to campus from May 27 to May 31, where “You won’t believe how much has changed, like the new Smith Campus Center (a.k.a. Holyoke Center) and Harvard Art Museums (a.k.a. The Fogg)….” If only those were the only changes this year.

In a “Reflections” essay for that volume, president emeritus Neil L. Rudenstine recalled “my first undergraduate Harvard class.” (At their Baccalaureate, he joked, “You and I began together as freshmen four years ago and, despite my advancing middle age, I still consider myself a full member of the very classy class of 1995. Unfortunately, I learned just this morning…I will not be graduating on Thursday. Evidently my attendance this year has been appalling.”) Turning current, he pointed to other changes, recalling “my own undergraduate class of slightly stultified conformist types who entered college (not Harvard) in 1952…a studious all-male conglomerate—neither terribly effervescent nor sophisticated, and certainly not diverse. So it was a great relief to see all of you arrive in 1991 with your manifold differences, your fine array of divergent talents and perspectives, and your capacity to pierce the curriculum to its very Core—and well beyond.” Looking ahead, he hoped that the class members “may go forward—in your various ways—to do what you can do to help rescue our precarious world, and begin to heal the ills that beleaguer our faltering nation and planet.”

Next on deck, the 1995 Class Day speaker, baseball great Hank Aaron, recalled playing in the Negro Leagues, when “my main goal was to earn a spot in the starting lineup because the starters were the only players given warmup jackets, and there were a lot of cold nights in the dugout.” A fabulous career later, he wrote, “I meet Harvard graduates all over the world in my travels, and it is very nice to be able to tell them that I not only have been on campus, but I spoke to one of its best classes ever.” (When he did so, a quarter-century ago, he told listeners “a story about a young man who after graduating last year went running up to his father and said, ‘Look, Dad, I got it! I got my A.B. from Harvard.’ To which the father replied, ‘Son, that’s fine. We are all real proud. Now it’s time for you to go to work and learn the rest of the alphabet.’”)

In keeping with other traditions of the week, the Harvard Medal, recognizing extraordinary service to the University (read a full report here), was conferred on:

- David L. Evans, retiring after more than a half-century of service in admissions;

- Leila T. Fawaz, Ph.D. ’79, long-time Overseer; and

- Joseph J. O’Donnell ’67, M.B.A. ’71, retired Corporation member, powerhouse University fundraiser, and co-chair of The Harvard Campaign.

And the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences recognized leading alumni contributors to knowledge and society (read more about the honor and recipients here), awarding its Centennial Medal to:

- Stephen Cook, Ph.D. ’66, a pioneering mathematician;

- Albert Fishlow, Ph.D. ’63, the preeminent scholar of Latin American economic development and history;

- Margaret Kivelson ’50, Ph.D. ’57, who has led discoveries about other plants for NASA and the European Space Agency; and

- Helen Vendler, Ph.D. ’60, a world-renowned poetry critic, retired Porter University Professor, and beloved teacher and mentor to generations of Harvard students.

The Degree Ceremony Begins

For those who tuned in at 10:30 a.m., there was a slide show, accompanied by the Harvard University Band, of University students, especially, and scenes (with images rolling forward from 2016—the seniors’ freshman year—and photos of Commencements past): vivid reminders, lest they forget, of an earlier era when people enjoyed doing things in close proximity to one another—in classrooms and labs, at athletic events, in performances, or just hanging out—without face masks. A brief opening video followed, featuring congratulations from alumni in service—medical personnel, a first responder, a member of the military—and others, including Corporation senior fellow William F. Lee; Boston mayor Marty Walsh; the Commonwealth’s attorney general, Maura Healey ’92, and governor, Charlie Baker ’79; and Law School class day speaker Bryan Stevenson , J.D.-M.P.A. ’85, LL.D. ’15.

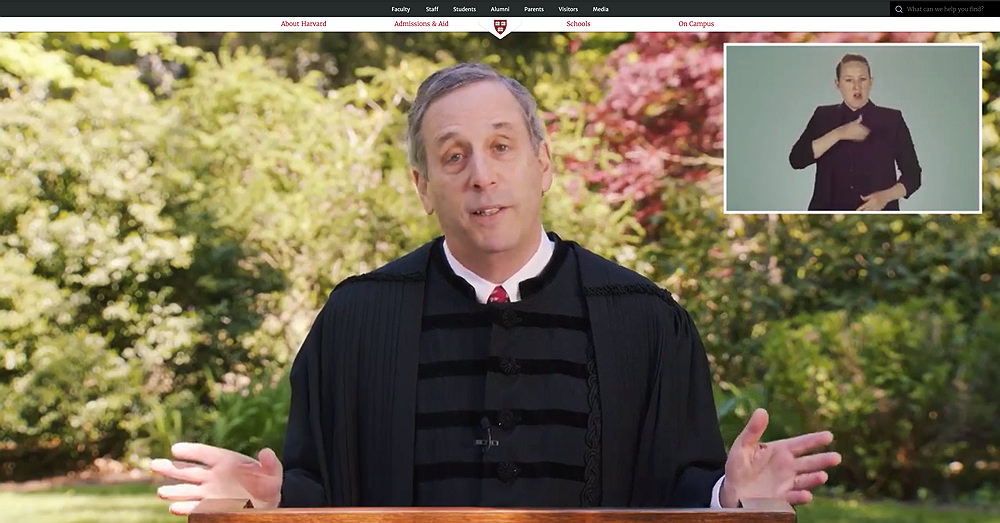

President Lawrence S. Bacow played a more forward role than in traditional Morning Exercises, hosting the virtual degree-conferring ceremony—and inviting the graduates to lead lives of service to a world very much in need.

Screenshot taken by Harvard Magazine

The recorded online ceremony began at 11:00 sharp. In normal years, the president would be confined to the rear of the Commencement platform, somberly berobed in black and perched on the ungainly three-legged chair with which Harvard tortures its leader. Thence he would utter the designated words conferring degrees on each cohort of candidate students as their deans present them, and on the honorands—saving his breath for the afternoon meeting of the Harvard Alumni Association and his major address. But in the virtual degree-conferring ceremony, President Bacow, berobed, was more the emcee and showrunner.

“I’m sure you’ve imagined this moment for quite some time,” he began, welcoming the members of the class of 2020 (read his full remarks here). “But let’s face it: It’s far different than any of us could have predicted when this semester began….” Finding the upside in the situation, he joked, “Everyone you love—and everyone who loves you—can actually attend. No tickets are required”—nor scrambling for good seats, nor preplanning where to park. (Sadly, it has been no challenge whatsoever to park anywhere in the Square in recent months.) The president also guaranteed that it would not rain on the graduates. (It did not—but he may wish to have saved that promise for a future occasion. For the record, it was a clement morning in the eeriely empty Tercentenary Theatre: overcast to partly sunny, breezy, with the temperature in the low 70s, and increasing humidity.)

Bacow lauded the graduates for “your years of hard work” and the way, when faced with obstacles, “each of you mustered your courage, set your sights, and overcame the insurmountable. You expanded your understanding of who you are and what you can do. And you discovered the truth about yourself—a veritas worth pursuing if there ever was one.”

After encouraging the class to spend a day celebrating themselves and resting upon their laurels, he summoned them back:

But only for a day because tomorrow is about everyone else.

How will you use your gifts and your Harvard education to make the world a better place for others? How will you help to ensure that others have opportunities similar to those that you’ve enjoyed? And how will you create a future in which all people are equipped to do their best work and to be their best selves?

Humanity needs people who are willing to devote themselves to asking questions, hard questions, sometimes even uncomfortable questions—people who are willing to work hard to perfect this imperfect world that we inhabit—people who care more about others than about themselves.

You are those people. And when we gather in person sometime later to celebrate your graduation—when we have a chance to relish all the pomp and circumstance in one another’s company that we cannot do today—I will want to know how you are helping to improve the lot of humanity—where you’ve been and where you think you’re going.

He then passed the baton to the student speakers.

Michael J. Phillips ’20, Undergraduate English Speaker: “The Keys and the Canvas”

Undergraduate orator Michael Phillips was arriving on campus his freshman year, standing beneath Johnston Gate, when his mother wrapped a set of keys around his neck. Each was engraved with a word that would shape his Harvard experience: “believe,” “fearless,” and “inspire.” He walked into his dorm room minutes later to find a list of alumni who held the keys to that room before him—as he recalled in his address (read his full text here):

The first name I read was Henry David Thoreau: the prophetic essayist and abolitionist. It was a glimpse into the greatness of what this surreal world was capable of. “Maybe,” I thought, “it just might change me for the better.”

Public speaking and reflection are part of Phillips’s DNA (and seen up close, intimately, on the screen—as if in a Zoom classroom—was a far more intense experience than one might have in the vastness of Tercentenary Theatre). His father, Michael, is senior pastor of Baltimore’s Kingdom Life Church and serves on the city’s board of education; his mother, Anita, is an educator, life coach, and host of a podcast. “Growing up, watching them, I was figuring out how my path would line up with that type of service,” Phillips says. “That’s kind of what drove my whole pathway to college.”

But at Harvard, surrounded by ambitious people, it was tough to stick to the goals he had entered Harvard to pursue:

Freshman year, we spent our energy writing viscerally scribbled applications to social orgs. Sophomore year, we exchanged our space suits for business suits to rush to networking events. Yet with every superhuman attempt, shortcomings were revealed…. The place we imagined as kids, a place defined by the pursuit of passion, became troubled by the fear of rejection.

Over time, Phillips found his footing in a more familiar path. After beginning as an economics concentrator, he switched to social studies, and later to sociology, inspired by the course “Dilemmas of Equity and Excellence in American K–12 Education.” From there, he took more courses on race and political theory. Outside the classroom, he found meaning in other activities. For two years, he led the David Walker Scholars program—providing mentorships for black middle-schoolers—and volunteered as a high-school teaching fellow for the W.E.B. Du Bois Society. On the side, he competed for the Harvard Classics Club basketball team.

Michael J. Phillips

Photograph courtesy of Michael J. Phillips

Rejection also played a part in his development when he found himself swept up in a wave of job recruiting. As his friends received acceptances to prestigious internships, Phillips was rejected by his top option. It ruined his confidence. “I didn’t realize it would have such a debilitating effect on me,” he says. “But in the face of the pain that I felt, I was like, ‘Why on earth is this so disorienting?’” He realized he was looking not just for a job, but for affirmation; chasing accolades, he felt, could become a never-ending process.

He decided not to let that happen. Before his senior year, Phillips resolved to spend his last semester abroad, planning to travel to São Paolo, Barcelona, and finally to Cape Town, South Africa—a meaningful site for past civil-rights leaders that he wanted to experience for himself. The group didn’t make it to Cape Town, deterred by the coronavirus pandemic, but along the way Phillips saw the “different types of public service that were out there and available to do."

Once he goes to work in Bain’s Chicago office after graduation, Phillips wants to make sure he doesn’t lose sight of what’s important. “I use ‘we’ a lot in the speech because I felt like I was talking to myself as much as I was talking to anyone else,” he says. “If I’m not looking to make the people around me and the community around me better with the gifts I have—if that’s not the primary motivation—then I’ve failed.” He concluded his speech on that note:

Harvard will change you. Let it continue to change you. Let it make you keenly sensitive to injustice. Let it make you more empathetic to struggle. Let it embolden you to make change. Let it make you all of these things because to become anything else would be to forfeit any meaning in being a Harvard graduate. We were fortunate to fly high enough that we might grab the moral arc of the universe itself. May we bend it in the right direction.

Sana Raoff ’12, Ph.D. ’18, M.D. ’20, Graduate English Speaker: “This View of Life”

Sana Raoof—a veteran of a full-dress Harvard Commencement in 2012—was raised a speaker. When she was a toddler, her grandfather, Dr. Abdul Raoof, had her begin dinner parties, family gatherings, and any sort of group occasion with a formal, memorized address. “And it would always start the same way,” Raoof says: “Ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, may I have your attention—your attention please.” When she was in elementary school, he named topics and had her deliver short, extemporaneous speeches.

Growing up in a multigenerational Indian Muslim home on Long Island, Raoof says she felt as if she had two sets of parents. With her mother and father completing their medical training, her grandparents drove her and her brother, Sahir, to their various activities. At home, her grandfather—the former director of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)—supplemented the siblings’ school-work with a self-styled curriculum focusing on “hard” skills like math and science, and public speaking. She learned calculus in middle school, years before her classmates; when she was 11, she started going to “genetics camp,” and in high school, she began performing research at the Cold Spring Harbor Lab.

Sana Raoof

Photograph courtesy of Sana Raoof

The intensive academic training, with its hard-to-summarize depth and breadth, paid off. She won the New York State debate championship twice, and in 2008, was one of three students to win the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair. As an undergraduate, she concentrated in chemistry and physics.

Dr. Raoof’s desire to educate his grandchildren stemmed from his early life in poverty. As an orphan in India, he struggled for food and shelter. “In hopes of a scholarship, he studied under streetlights swarming with bugs,” Raoof writes. Eventually, he was admitted to Columbia, where he earned a Ph.D., as she told the virtual crowd, vivid in her doctoral gown against a backdrop of bougainvillea and foxbloves (read her full text here):

My grandfather’s mission evolved from early challenges. Education gave him freedom, so he became an educator. Hungry in childhood, he provided food for his students. Homeless in his village, he later housed people under his own roof. Dependent on scholarships, he funded scholarships for students in need.

When her grandfather was too old to leave the house or walk downstairs, he wrote letters to politicians, advising them about education policy. Raoof typed them out and mailed them off.

Raoof, in her own life, has taken this educational mission to heart. As she designed drugs for lung-cancer patients during the Ph.D. portion of her M.D.-Ph.D., she scheduled meetings with members of the Massachusetts Joint Committee on Public Health and drove back to New York to educate legislators on smoking and health. She wrote public-health policy briefings and provided expert testimony as a lung-cancer researcher. A few of the bills she advocated eventually passed, including an increase in the legal smoking age in Nassau County, Long Island. She has always made it a point, she says, to make sure scientific developments and information get out into the real world. “I think it’s something that oftentimes you forget about at Harvard—that there might be a world outside of academia.”

After her grandfather passed away last summer, Raoof took a trip to the Library of Congress with her husband, Irineo Cabreros ’12, where they spent several days, morning to night, researching his work. She found Dr. Raoof’s fingerprints on the educational systems of Afghanistan, Kenya, and India. “It made me much more appreciative of what an incredible journey he had and what an incredible impact he had on tens of thousands of people around the world,” she says. “If you give someone education, you give them the ability to take charge of the conditions of their life, for the rest of their life.”

Raoof’s speech is about her grandfather, but it’s also about evolution—her own academic specialty. “In times like these,” she writes, “we can remember that the greater the adversity, the greater the need for evolution on all scales, from the individual to the nation.”

My grandfather told me, “Make a plan to change the world and do not rest until you achieve it.” It is when we are at our lowest points that we look internally, develop our strengths, and gain the purpose that may lead us to our highest points in the future. So, graduates, let us turn this disruption into our vision, and this challenge into our evolution!

Pomp, under the Circumstances

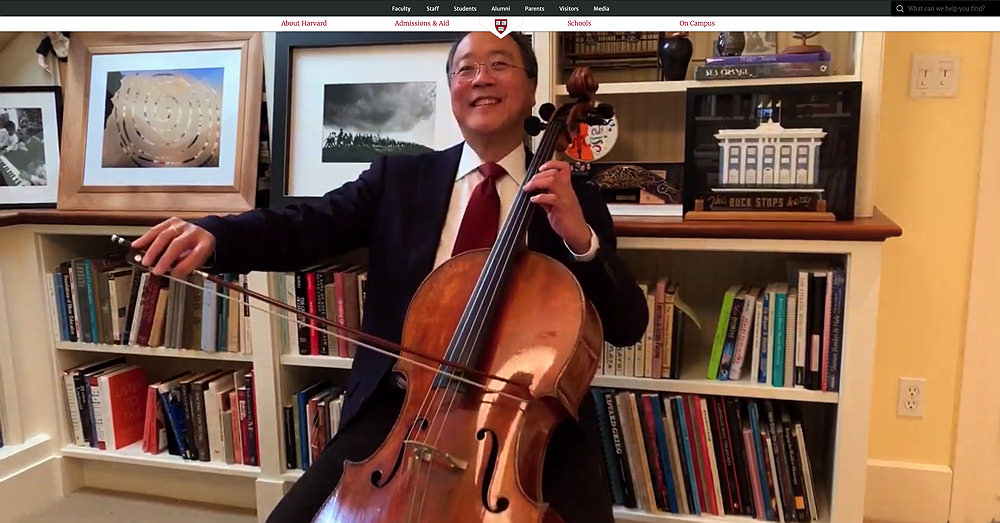

The first musical interlude was performed by cellist Yo-Yo Ma ’76, D.Mus. ’91 (profiled here), renowned for his sublime musicianship and revered for his charisma and warmth. He was introduced by his College classmade Alan Garber ’76, the provost. A familiar presence—his Silkroad collective engages with students regularly, and its offices are on campus, in Allston—Ma performed two pieces. He recorded the first, “Simple Gifts,” the Shaker song by Elder Joseph Brackett (1848), in a duet with Alison Krauss on a 2001 album. The second, the “Sarabande” from Cello Suite No. 3 in C Major, by Johann Sebastian Bach, is the sort of pure, signature work that has endeared Ma to audiences worldwide.

Yo-Yo Ma performed the first musical interlude, a medley of his arrangement of “Simple Gifts” and the “Sarabande” from Cello Suite No. 3 in C. Major, by J.S. Bach.

Screenshot taken by Harvard Magazine

As the music ended, Ma whispered a congratulations to the graduating students.

Then it was on to the official business: the conferral of degrees so the candidates, notwithstanding the deferral of Commencement proper, could head off into the world transmogrified into real Harvard graduates, with the credential to prove it. This work normally involves the deans, speaking separately, presenting their respective worthies (and occasionally ad libbing a bit); the respective students living it up by cheering and waving something or other (flags for B School M.B.A.’s-about to be; children’s books for the Ed School cohort; inflated globes for the K School scholars; and for the M.D.s and dentists and public-health experts—the latter, with their astonishing epidemiological faculty members, deserving a huge hand this year—stethoscopes or tooth brushes or condoms as the mood suits them). And the president, by virtue of authority delegated to him, confers the appropriate degrees en masse, and on to the next school.

Online, the whole happy rigmarole was streamlined, considerably. The provost introduced the proceedings, and the deans appeared, suitably robed (that’s what they look like at home, where they taped their remarks—but presumably they don’t usually dress that way for Zoom appointments), one after another, lickety-split: Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, Extension School, Dental School, Medical School, Divinity School, Law School, Business School, Design (represented by Sarah Whiting, appearing at her first graduation as dean, despite being treated for cancer), Public Health, Education, Kennedy School, and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and College (with FAS dean Claudine Gay welcoming the youngsters “joyfully, albeit remotely” to the ranks of educated women and men). And then the president performed one overarching, super act of degree-conferring and encouraged hugs and kisses around the world. (Each school is conducting a separate online degree ceremony for its students in the afternoon.)

Thereupon, in a further bit of streamlining, the Afternoon Exercises were reduced to greetings to the new graduates, welcoming them to the ranks of alumni worldwide, from Alice E. Hill ’81, Ph.D. ’91, president of the Harvard Alumni Association. There is no more worldwide representative than she—a resident of Australia, who was spared the arduous trip to the Northern Hemisphere this time as she put in a virtual appearance from Melbourne. Nor was that the only change in her plans: her son Hamish, a member of the College graduating class, was among those she had hoped to anoint an alumnus, in person. Bacow observed that she was speaking from tomorrow, as it is already Friday in Australia.

“Home”: Leaning into Intimacy and Connection

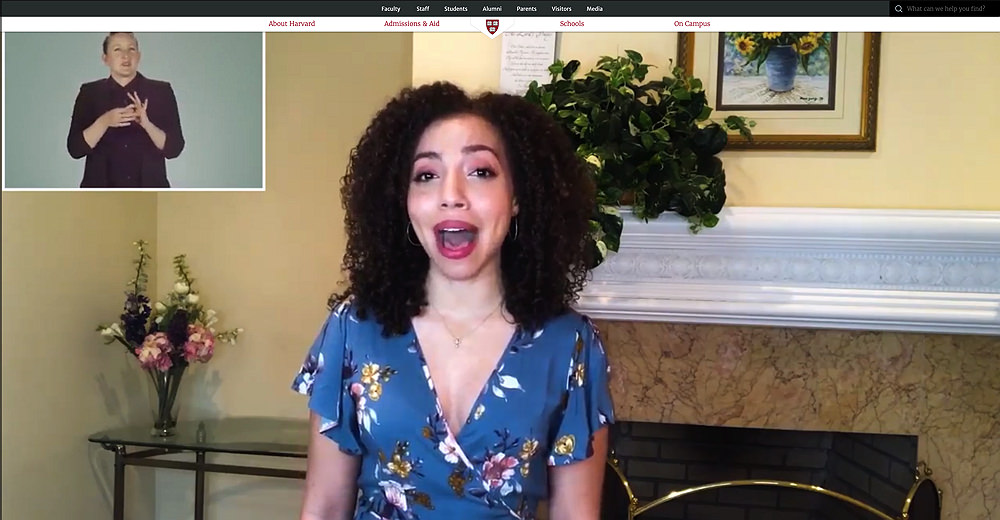

The second musical interlude may have struck even more directly at the emotional heartstrings than Ma’s artistry. Madeline A. Smith ’14 (an accomplished music director, arranger, and conductor) and Ashley M. LaLonde ’20 (a singer, actor, and dancer)—who left dominant impressions on the campus’s musical and theatrical scenes during their respective undergraduate careers—teamed up for a version of “Home,” by Charlie Smalls, from The Wiz, the “super soul” musical version of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Ashley M. LaLonde ’20, accompanied by Madeline A. Smith ’14, tugged at hearts by performing “Home,” from The Wiz

Screenshot taken by Harvard Magazine

LaLonde, who has performed professionally since she was in high school, was born and raised in New York, where she grew up singing in church. She sang the song previously, during a production of The Wiz when she was 17 (it became part of her Harvard application). A sociology concentrator with a minor in theater and a certificate in Spanish, she has performed in numerous Harvard and American Repertory Theater productions, and in 2019 was a member of the Hasty Pudding Theatricals’ first coed cast. She won the Radcliffe Doris Cohen Levi Prize for Musical Theatre last year, and is now pursuing a full-time acting career in New York City.

Smith accompanied LaLonde on the piano. A music and classical civilizations concentrator, she, too, won the Doris Cohen Levi Prize, in 2014. She made her Broadway debut in 2016 as the conductor for Waitress, when she was 24 years old—and very possibly the youngest woman to take up the baton in a Broadway orchestra pit. Her Off-Broadway and regional theater credits are numerous.

If ever there were a story about a sudden removal from home, and loss and longing, and the journey back to home and friends, of course, Dorothy’s nailed it. She sings “Home,” the iconic ballad in the musical, toward the end of the play, after she has bid farewell to Oz and her friends there and is about to click her heels together to get back to Kansas. As LaLonde put it, “‘Home’ felt like the right song because Harvard is our home. And you don’t know how much you love something until it’s taken away from you. I’ve been away from campus since December [when she graduated early], but we all feel that way about Harvard now.…For most students in the class of 2020, their home was taken away from them because of the pandemic. And so, what a beautiful way to say Harvard is our home, that it will always be our home.… Home so much more than a place—it’s a people and a feeling.”

For this rendition, she continued, “It’s a giant, belty finale song, with tons of emotional meaning. So I wanted to do it justice, but also knew that I wasn’t performing it as part of The Wiz, so it’s different vocally and in the acting and texture. I’m not on a Broadway stage singing to a giant audience; I’m at my parents’ house in front of a fireplace singing directly into an iPhone, and no one’s there.”

Accordingly, she decided to treat it “more like it’s a conversation between me and a peer about what we think of when we think of home and what home means right now in this moment and in relation to Harvard.…It’s more intimate. I tried to lean into that intimacy and that connection.” But she still belted it out.

Students, particularly seniors, who found themselves severed from their campus community and friends between March 10 and March 15, only to end their Harvard education through the Technicolor™ looking glass of Zoom, could no doubt find their feelings captured from the opening of the lyrics:

When I think of home

I think of a place where there's love overflowing

I wish I was home

I wish I was back there with the things I been knowing

through the “And just maybe I can convince time to slow up/Giving me enough time in my life to grow up,” to the travails of “Suddenly my world has changed its face” and “I have had my mind spun around in space” (and how, this year!), to the reassuring concluding lines about finding “a world full of love…Like home….” (All lyrics © Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp.) The song seemed written for the moment.

The University, professors, and staff members who came to know these students during their residence certainly wish, devoutly, that Harvard can remain a home for them, despite this topsy-turvy spring semester—and found, in these two supremely talented young graduates, a loving, memorable way to extend an invitation to return.

Martin Baron: “Misinformation, disinformation, delusions and deceit can kill.”

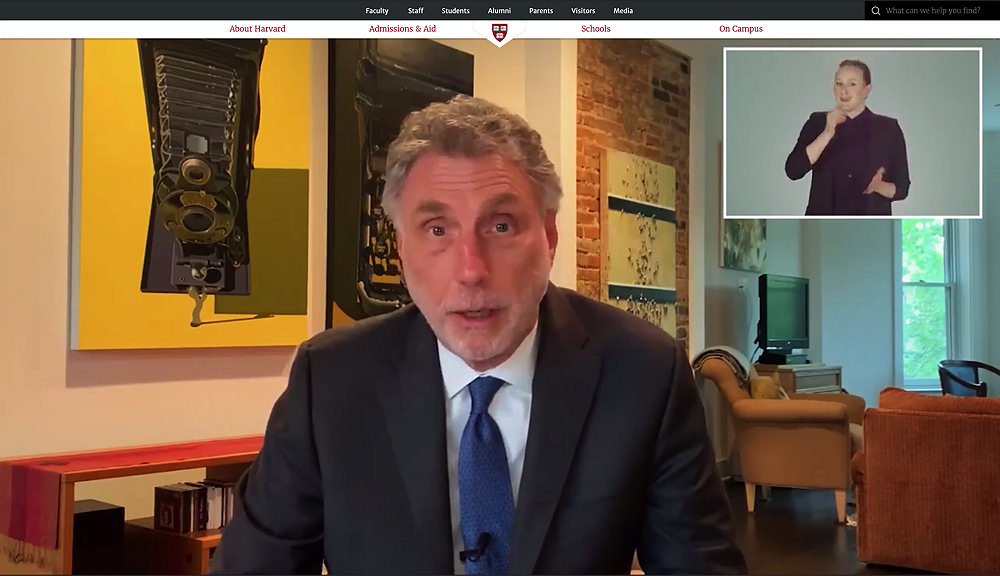

Harvard does not confer honorary degrees in absentia. Given the mandatory absences of all and sundry from campus, they were not a part of today’s truncated ceremony. But journalist Marty Baron, the intended honorary-degree recipient who would have been the afternoon speaker (along with President Bacow), did make his (recorded) address, lending an anchoring element of a traditional graduation day to the proceedings. Bacow, who made the introduction, said that neither he nor Baron “remotely” anticipated the circumstances when he extended the invitation last summer—“but here we are, or perhaps I should say, here we aren’t.” He lauded Baron as someone who never sought the spotlight, preferring to cast it on matters that needed to be illuminated. The journalist, he continued, pursued a life’s work that resonated strongly with Harvard’s mission of pursuing truth.

Marty Baron, executive editor of The Washington Post and the day’s honorary guest speaker, gave a sobering address about the threats to freedom of the press, free expression, and the pursuit of Veritas.

Screenshot taken by Harvard Magazine

As the leader of the major news enterprise at the heart of contemporary Washington, D.C., the Post’s executive editor could be expected to say something about the miasma that passes for political discourse today. Baron had considerably more to say than that. He spoke from home, where modern art on the wall behind him depicted the reporter’s essential tools: a manual typewriter, and an old-style accordion camera.

The day’s address, he said, was “an opportunity to speak about subjects that I believe are of real urgency. Especially now during a worldwide health emergency” (read his full address here). He continued:

I would like to discuss with you the need for a commitment to facts and to truth.

Only a few months ago, I would have settled for emphasizing that our democracy depends on facts and truth. And it surely does. But now, as we can plainly see, it is more elemental than that.

Facts and truth are matters of life and death. Misinformation, disinformation, delusions and deceit can kill.

Here is what can move us forward: Science and medicine. Study and knowledge. Expertise and reason. In other words, fact and truth.

I want to tell you why free expression by all of us and an independent press, imperfect though we may be, is essential to getting at the truth. And why we must hold government to account. And hold other powerful interests to account as well.

He reviewed the winding path toward a genuinely free American press, secured only in the wake of the examples of “the authoritarianism of Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan.” He recalled his service at The Boston Globe, beginning in mid 2001, which coincided with the first revelations of the abuse of children by local priests—and the failure of the Catholic Church hierarchy to address the problem (and indeed, its complicity in covering it up). Having arrived on the scene, he pushed to challenge a judicial order sealing the records that could illuminate the abuse and cover-up, leading to the unmistakable conclusion that “The cardinal had covered it all up.”

“Late in 2002, after hundreds of stories on this subject, I received a letter from a Father Thomas P. Doyle,” Baron related. “Father Doyle had struggled for years—in vain—to get the Church to confront the very issue we were writing about. He expressed deep gratitude for our work. ‘It is momentous,’ he wrote, ‘and its good effects will reverberate for decades.’ Father Doyle did not see journalists as the enemy. He saw us an ally when one was sorely needed. So did abuse survivors.”

Baron said he kept that letter on his desk, “a daily reminder of what journalists must do when we see evidence of wrongdoing”—a theme also sounded by the civil-rights pioneer and congressman John R. Lewis, LL.D. ’12, the 2018 Commencement speaker. Lewis, Baron observed, said, “When you see something that is not right, not fair, not just, you have to speak up. You have to say something; you have to do something.” Journalists, Baron continued, “have the capacity—along with the constitutional right—to say and do something. We also have the obligation. And we must have the will.”

Addressing the graduates directly, he said, “So must you. Every one of you has a stake in this idea of free expression.”

He reviewed the depressing decline of press freedom around the globe—an immediate precursor to leaders’ efforts to “destroy free expression itself.”

“Truth,” he said, “is not a matter of who wields power or who speaks loudest. It has nothing to do with who benefits or what is most popular. And ever since the Enlightenment, modern society has rejected the idea that truth derives from any single authority on Earth.” Instead, “To determine what is factual and true, we rely on certain building blocks. Start with education. Then there is expertise. And experience. And, above all, we rely on evidence”—the lack of which can jeopardize human health and safety.

As “education, expertise, experience and evidence” are “devalued, dismissed and denied,” the idea of objective fact is being undermined, “all in pursuit of political gain.” As evidence, Baron cited “a systematic effort to disqualify traditional independent arbiters of fact,” from the press to the “courts, historians, even scientists and medical professionals—subject-matter experts of every type.”

Citing Hannah Arendt, Baron warned about the dangerous possibility of totalitarianism. In opposition to the devolution of fact and truth, he cited numerous recent examples of journalism that exposed wrongs, and prompted reform—from matters of war to the pervasiveness of sexual assault.

Drawing together the truth-seeking missions of universities and news enterprises, he concluded with a passage from W.E. B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. ’95:

In 1935, distressed at how deceitfully America’s Reconstruction period was being taught, Du Bois assailed the propaganda of the era.

“Nations reel and stagger on their way,” he wrote. “They make hideous mistakes; they commit frightful wrongs; they do great and beautiful things. And shall we not best guide humanity by telling the truth about all this, so far as the truth be ascertainable?”

At this university, you answer that question with your motto—“Veritas.” You seek the truth—with scholarship, teaching and dialogue—knowing that it really matters.

My profession shares with you that mission -- the always arduous, often tortuous and yet essential pursuit of truth. It is the demand that democracy makes upon us. It is the work we must do.

We will keep at it. You should, too. None of us should ever stop.

At the conclusion, Bacow thanked him “for your own work to reveal the world as it is.”

Envoi

Appearing in her role as interim Pusey Minister of Memorial Church, Stephanie A. Paulsell gave the benediction. Acknowledging the participants’ joy mingled with “a measure of grief” given the circumstances, she wished for the graduates the “freedom to let your lives be shaped by your deepest questions and your fiercest hopes.” Noting the moment, she concluded, “May you and those you love travel safely through this time.”

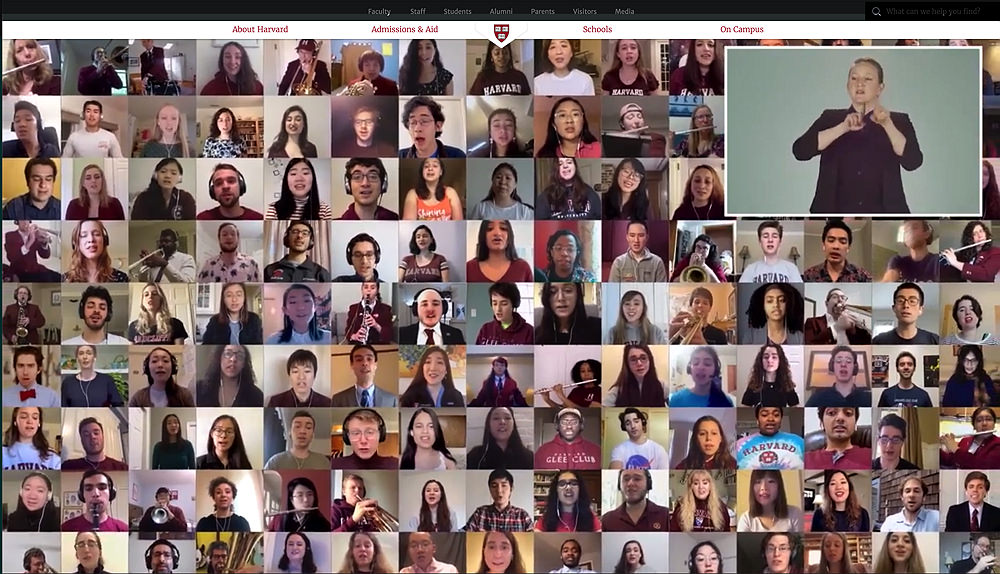

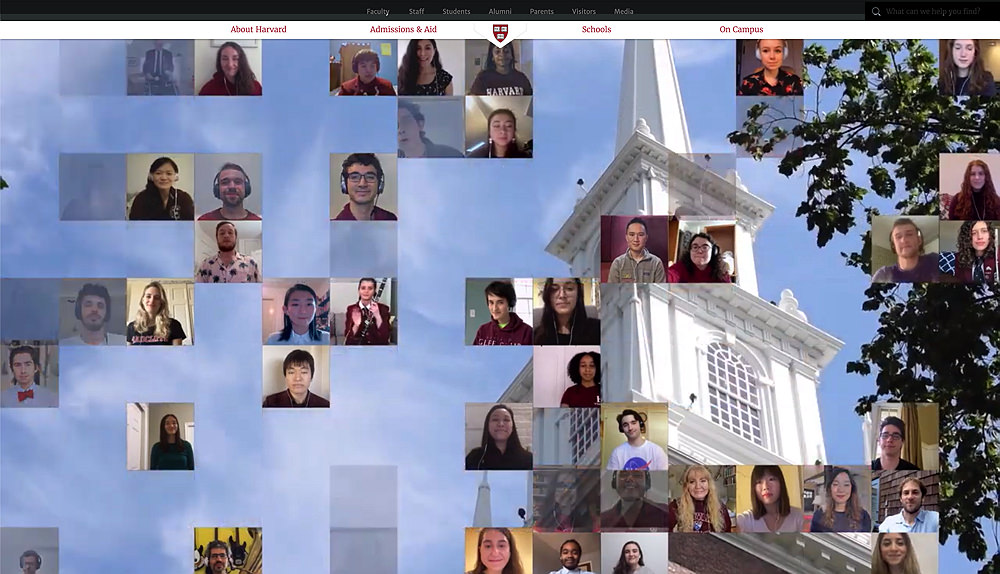

A University chorus joined forces, and voices, to sing “Fair Harvard” at the conclusion of the video graduation ceremony.

Screenshot taken by Harvard Magazine

Finally, since there cannot be a Harvard graduation without some band music, and a rendition of “Fair Harvard,” the Office for the Arts and the music directors pulled a final bit of technological magic out of their collective hats, melding student voices and instrumentalists from across the University and its schools, some in headphones, into a synched singing of the alma mater—followed by the traditional ringing of the bells—virtually, of course.

Whatever the community lacked in physical presence in Tercentenary Theatre on the warm, dry morning of May 28, 2020, it decisively demonstrated in spirit and in song. “Calm rising thro’ change and thro’ storm,” indeed.