As an editor at Mademoiselle magazine in New York, Carter Burwell’s mother used to chase down writers like Truman Capote and Dylan Thomas to get their overdue pages. She loved going to jazz clubs and staying till closing time. When the musicians went home, they kept right on jamming. “It really impressed her that there are these people whose work and whose play were the same thing,” Burwell ’77 said. “I feel lucky to be spending my days doing something I really do enjoy.”

That joy is palpable in Burwell’s indelible work as a composer for movies. Think of the snow-blind opening of the Coen Brothers’ film Fargo,with its rustic strings (a Scandinavian hardanger fiddle) and funereal grandeur as the hopeless protagonist’s car heaves into view. Or the Texas noir Blood Simple—also directed by Joel and Ethan Coen, making their 1984 debut alongside Burwell—and its seductive piano motif, dancing above low chords before tumbling down. Burwell’s fresh idioms and complementary timbres are as vital as any actor’s performance, and his decades-long mind meld with the Coens is one of the most original collaborations in American cinema—a rich, continuing portrait of the country’s idiosyncratic corners. “They like to be very specific about the way people speak and the way they dress and these little miniature cultures,” Burwell says, “And that often calls for me to be very specific with films like Raising Arizona or True Grit.”

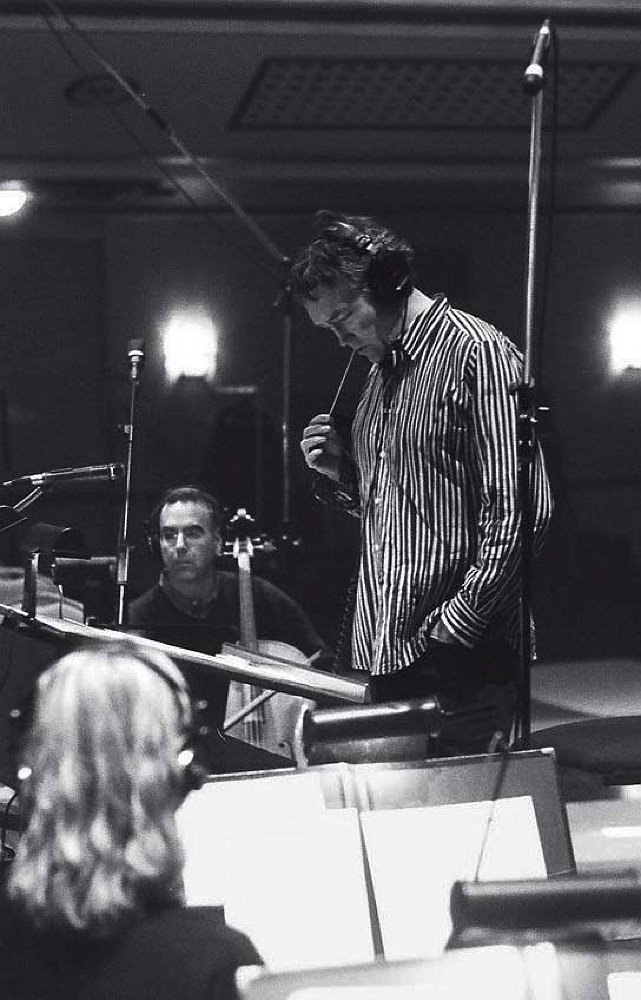

Burwell at work during the Coens’ 2010 remake of True Grit

Photograph courtesy of Dean Parker

Burwell’s current project finds him in another time and place entirely: medieval Europe. That’s the setting of Catherine, Called Birdy, an upcoming film directed by Lena Dunham, best known for the hit HBO show Girls. Burwell values independent filmmakers, and the admiration is mutual: Dunham reached out to him directly. Working out of his home studio in Amagansett on Long Island—where he lives with his wife, the artist Christine Sciulli, and three children—he conjured soundsfor her comedy about a 14-year-old girl in thirteenth-century England, based on a 1994 children’s novel of the same name. “When I read Lena’s script, I had an immediate reaction as to what I thought the music should be,” Burwell says. “This does not always happen.” A period film can pose challenges of authenticity, but he found guidance in the story’s journal-driven point of view rather than researching lutes and recorders. “Vocals are timeless and could be very easy for putting you in the mind of the girl,” he says. He thought of the innovative 1970s French group The Swingle Singers and vocal work by composer and singer Meredith Monk.

Dunham liked the concept and Burwell’s keyboarded mock-up, which left him to weave 45-odd minutes of music and arrange it for a group he had in mind, Roomful of Teeth. When interviewed, he was in the midst of composition, a process that can require 16-hour workdays. Sometimes, as few as six weeks separate the start and delivery of a score—a conclusive stage of moviemaking that clinches (and sometimes rescues) a film’s emotional tone and sense of cohesion. Burwell has worked with filmmakers such as Spike Jonze (Being John Malkovich), Sidney Lumet (Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead), Todd Haynes (Carol, Mildred Pierce), Julian Schnabel (Before Night Falls), David Mamet (The Spanish Prisoner), and Catherine Hardwicke (Twilight), as well as composing for theater, dance, and recently television. His latest score for Joel Coen is 2021’s The Tragedy of Macbeth.

Burwell says that he had no formal training. His formative musical experience came when a high-school friend taught him the fundamental chords of the blues for improvisation. Otherwise, “I probably wouldn’t be a composer,” he says. At Harvard he intended to study math, but steered into creative pursuits. “I found my people at the Harvard Lampoon,” he says, in the era of Jim Downey ’74 (Saturday Night Live) and George Meyer ’78 (The Simpsons). Burwell studied animation with artists Mary Beams and George Griffin, and electronic music with Ivan Tcherepnin, longtime director of the Harvard University Electronic Music Studio.

Architecture beckoned to Burwell as a career, until Iggy Pop set him straight. “In the spring of 1977, Iggy Pop played a gig at Harvard Square Theater. The opening band was Blondie, and playing piano for Iggy was David Bowie,” he recalls. “The whole thing was so exciting and sexy and of the moment. In other words, the opposite in every way from architecture.” Spurred by the looming recession and the rise of punk rock, Burwell chose music. He stayed at a loft on 14th Street in New York and played in bands into the 1980s, including an avant-pop outfit called Thick Pigeon.

In a roundabout way, that’s how he met the Coens: their sound editor, Skip Lievsay, knew Burwell and had heard Thick Pigeon play. When the Coens asked Burwell to compose music for Blood Simple, he had never scored a feature, much less had conservatory training. He regards this lack of experience as an asset. “I was not really exposed to any of the European traditions that dominated the first part of the twentieth century,” he says. Instead, he has tapped other influences: the sentimental warmth of Irish fiddles for Miller’s Crossing, minimalist piano and woodwinds for the clandestine same-sex romance of Carol, and for the ornery fervor of Three Billboards, the stomp-and-clap percussion of a Baptist church.

The result is melodious music that feels both ingenious and intuitive. Of A Serious Man—the Coen Brothers’ anxious tragicomedy of a Minneapolis teacher (and consummate shlemiel)—Burwell explains: “One of the main motifs is this loop of harp notes, and part of the unease is because it’s playing in units of three and units of four at the same time. So it takes 12 notes for even the simplest of melodies before they come back and repeat. It leaves you unanchored because you don’t know exactly where the downbeat is—is it here, or is it there?”

Between The Tragedy of Macbeth and Catherine, Called Birdie, Burwell jokes, “It’s my medieval year.” Spare and expressionistic, Macbeth opened the New York Film Festival last September, with Burwell’s largely stringed orchestration accompanying Shakespeare’s rush of words. “It allowed me to go in certain places with my writing where I can ignore all of nineteenth-century harmony, which is so often part of film score writing,” he says.

Asked if his blue-sky outlook in this and other films might define him as a peculiarly American voice, Burwell demurs. At first he credits the fine-tuned regionalism pursued by the Coens. Then he worked his way round to a realization. “In a way, my naiveté makes me a little bit more beholden to the folk traditions than any of the classical tradition,” he says. “If you include punk music as a folk tradition.”