“One of my small, goofy, weird joys is to get a very, very local newspaper from a small town, like my hometown, and read the police blotter,” says best-selling author of Little Fires Everywhere and Everything I Never Told You, Celeste Ng ’02. “Mr. So-and-So called the police again to report that someone moved his lawn chair from the backyard to the front yard for the third time.” She smiles. “Now there’s some drama.” A few words sprout intrigue. “There are small stories, but in another way, there’s this sense of them forming the fabric of the world we live in.”

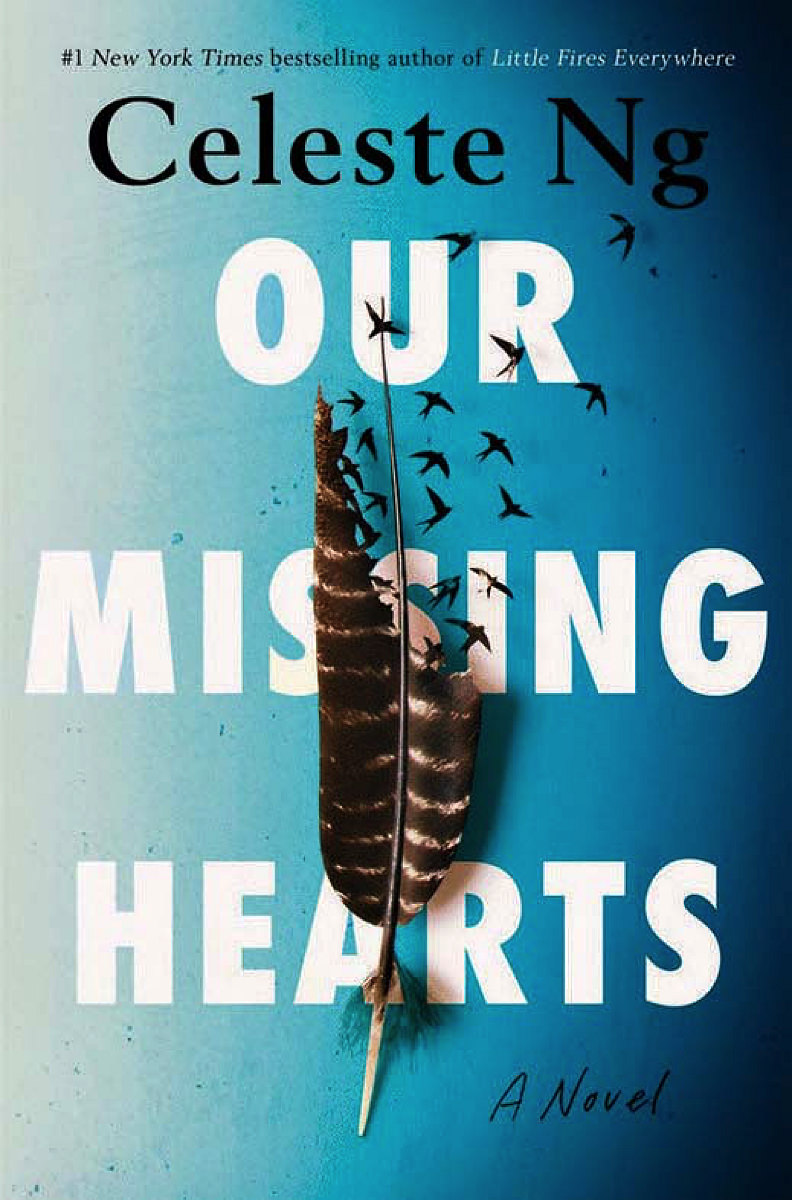

Ng’s latest novel, Our Missing Hearts, is her deepest exploration into the power of small stories, but she’s been weaving them together her whole life. It started as a child with the Chinese folk tales her immigrant parents told her, and with her favorite book, Harriet the Spy, in which the child protagonist—like Ng—takes notes on everyday moments. She says, “I knew that I always wanted to tell stories, because that’s how I make sense of the world.”

As a teenager in Shaker Heights, Ohio, she would spend hours with her friends at the Yours Truly restaurant (linoleum floors, high-back wooden booths), talking about who they’d grow up to be. She thought she’d be a scientist by day and a writer by night. “It was always do ‘something else’ and write on the side.”

Ng got to Harvard and her life branched before her in what felt like a hundred different ways. An English concentrator, she saw a life as a book publisher, an English professor, or maybe as an editor. She held on-campus jobs as an editorial assistant for Harvard Magazine (“I very studiously checked the class notes”) and as a server at the Faculty Club, and even ran a crafting business selling her clay miniatures to collectors on the Internet. She kept trying out different contenders for her “something else,” but the one constant was always “writing on the side.” Then a teaching fellow gave her some advice: “Instead of keeping writing ‘on the side,’ what if you put it in front?”

She finished her M.F.A. at the University of Michigan in 2006 and sold her first novel in 2012. “So, you can do the math,” Ng says. “There were six years there where I was basically like, ‘How do I pay the bills?’” She and her husband—whom she met freshman year when he held the door open for her at Greenough Hall—planned how they could support themselves while she wrote. She freelanced as a copy editor and briefly worked at a tech startup: “Basically, you kind of scrounge around and make it work. That’s the truth.”

All that time, she was writing her debut novel, Everything I Never Told You, about a daughter’s mysterious death that rocks a Chinese American family in small-town Ohio. “I basically got through writing my first book by telling myself, this isn’t going to publish, and if it does, no one is going to read it—probably not even my mom.” Her mom did read it, and so did millions of other people. Then, her sophomore novel, Little Fires Everywhere (2016)—about two unwillingly interconnected families and the multiracial adoption that divides the town of Shaker Heights—was a New York Times top bestseller and adapted into a Hulu television series starring Reese Witherspoon and Kerry Washington.

Her books hit the sweet spot between page-turning mysteries and literary fiction. They wade into complicated race and class dynamics and creatively render even the smallest details: the houses painted “dusty green, like the underside of a leaf,” a high school receptionist “built like a sofa cushion,” sweat drying on the skin to a “fine crystal grit,” “morning sunlight creamy as lemon chiffon.” But there’s always a mystery that readers want to solve.

After she finished Little Fires Everywhere in October 2016, she started writing about a mother-son dynamic: Chinese American poet Margaret Miu is devoted to her art, but her 12-year-old son Bird sees it as a rival for her attention. The mother of a 12-year-old son herself, Ng wondered, “Can they reach an understanding?” But then the November 2016 election happened, and it changed the story. “It felt like the book needed to reflect some of what was going on. It felt disingenuous to write this book in which none of these things happened—in which no one was thinking about police brutality or about censorship or xenophobia,” she says. “It felt dishonest to me, for this particular story, if everyone in it was just having a really happy, 2015-type time.”

If the settings and circumstances of her first two books were close to home for Ng—realistic fiction set in her home state—the new book was uncharted speculative territory. “Writing the book was like walking on sand,” she says. “You think you’re going one way and then the ground shifts and you’re sliding in a new direction.” She’d try to get words to flow by typing a favorite poem on her typewriter in the morning. “It’s not writing, but you’re feeling the contours of the words. It frees you up,” she says. She worked on the novel for years, but she couldn’t quite wrangle it.

Then, the pandemic arrived and triggered a new sense of urgency: she had to finish the story now. The plot took shape in real-time alongside the events of the past few years: parents and children separated at the U.S.-Mexican border and in Ukraine, widespread social reckoning in the United States, police brutality, and book censorship. The original kernel of a mother-son relationship grew into a story set in a not-so-distant future where the American government institutes strict censures for “un-American” behavior after a period of social and economic upheaval (not unlike 2020 to the present, a purposeful similarity). When Bird’s mother disappears, he goes on a journey to find her, following clues embedded in the folk tales she told him as a child.

“Putting this draft together during the pandemic, I was really thinking about: does art actually do anything, or am I just wasting my time? Should I train to do something that makes a tangible difference?” But the book speaks to the power of stories, and creating it reminded Ng why she writes. “Fiction can hold open a space in which things don’t have to be this way,” she says. “You don’t have to resign yourself to life being like this forever. You can find another way.”