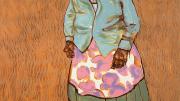

In T.C. Cannon’s Two Guns Arikara, a stately Native American sits in an armchair, loosely holding cartoonish blue firearms. He’s dressed in a mash up of what looks like U.S. cavalry pants, Plains Indian and European garb, and sports ornate silver jewelry. His puffy violet hair cascades down against a riotous purple, polka-dotted background.

Like many of the 30 color-splashed paintings in “T.C. Cannon: At the Edge of America” (through June 10 at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem), the salon-style portrait below reflects works by van Gogh, Gauguin, Matisse, and even Pop art. Yet Cannon’s bold figurative images also stand on their own as what he once called “real art,” made as “a declaration of love and guts.”

Two Guns Arikara (1974-1977)

Image © 2017 Estate of T. C. Cannon. Photograph by Thosh Collins

Born in Oklahoma in 1948, Cannon was a member of the Kiowa Tribe. He went to art school, completing Mama and Papa Have the Going Home Shipwreck Blues (1966)—a simply rendered Navajo couple sitting unwittingly at the crossroads of American and Native American cultures—that influenced the New Indian Art movement, and then surprised those he knew by joining the U.S. Army, ultimately earning two Bronze Stars for his service during the Tet Offensive. Back home, Cannon was apparently conflicted about his role in violence and in suppressing other indigenous peoples. During the next decade, he produced a significant body of work that was at once deeply personal and political, developing his voice on canvas, and as a musician and writer. The art spoke to the inevitable co-existence of past and present, pain and triumph, and to the turbulence of the times. And it still does.

At the museum, his 22-foot mural Epoch in Plain History: Mother Earth, Father Sun, the Children Themselves (1976-77) streams across a wall reveling in moonlit early tribespeople in animal skins, bison and hieroglyphics, a shamanistic bare-breasted woman with an owl and eagle in flight, and, finally, a Native American in a Stetson standing on a swath of green grass under a sun rendered as a woven textile. Cannon’s Kiowa name is Pai-doung-a-day: “One who stands in the sun.”

He completed about 50 major canvases, along with more than a hundred sketches, drawings, poems, and personal documents, many also on display. In all, they illuminate a flourishing artistic vision, albeit one cut short. Cannon died following a car crash in Santa Fe, at the age of 31.