The memories may be fading, but Harvard roared into the new millennium. In the wake of the $2.6-billion University Campaign, Neil L. Rudenstine bequeathed to his successor a $165-million surplus—a huge cushion in an annual budget then totaling $2.1 billion. In the recovery from the dot.com meltdown, and without the benefit of a successor campaign, the endowment (powered by double-digit annual investment returns from fiscal year 2003 through 2007) doubled, from $17.5 billion at the end of 2002 to $34.9 billion on June 30, 2007: the day before Drew Gilpin Faust officially became the University’s twenty-eight president.

During the six years between Rudenstine and Faust, an energetic Lawrence H. Summers fueled the institution’s animal spirits—if not always respecting its protocols. Harvard’s outlays climbed to $3.0 billion in fiscal 2006 (on their way to $3.5 billion by the end of Faust’s first year). As the flow of money to the schools became a torrent, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), whose ranks had held steady for four decades, grew from 592 ladder professors at the beginning of the 2000-2001 academic year to 709 just seven years later; enormous new laboratories were built to accommodate some of them. Summers pioneered a significant liberalization of financial aid, encouraged study abroad, and pushed for a generational overhaul of the College curriculum (subsequently reduced to a new sequence of General Education courses).

Most momentously, in early 2007, Harvard filed its 50-year plans for Allston with Boston regulators, envisioning 10 million square feet of new buildings: homes for the education and public-health schools, an arts and museums complex, and vast scientific research facilities. On Monday, July 2, her first day in Massachusetts Hall, Faust met with Christopher M. Gordon, head of the University’s Allston Development Group; subject to financing, he said later, the question about the massive first phases of construction was “how fast they could be built. Is it five years, 10 years, 15 years?”

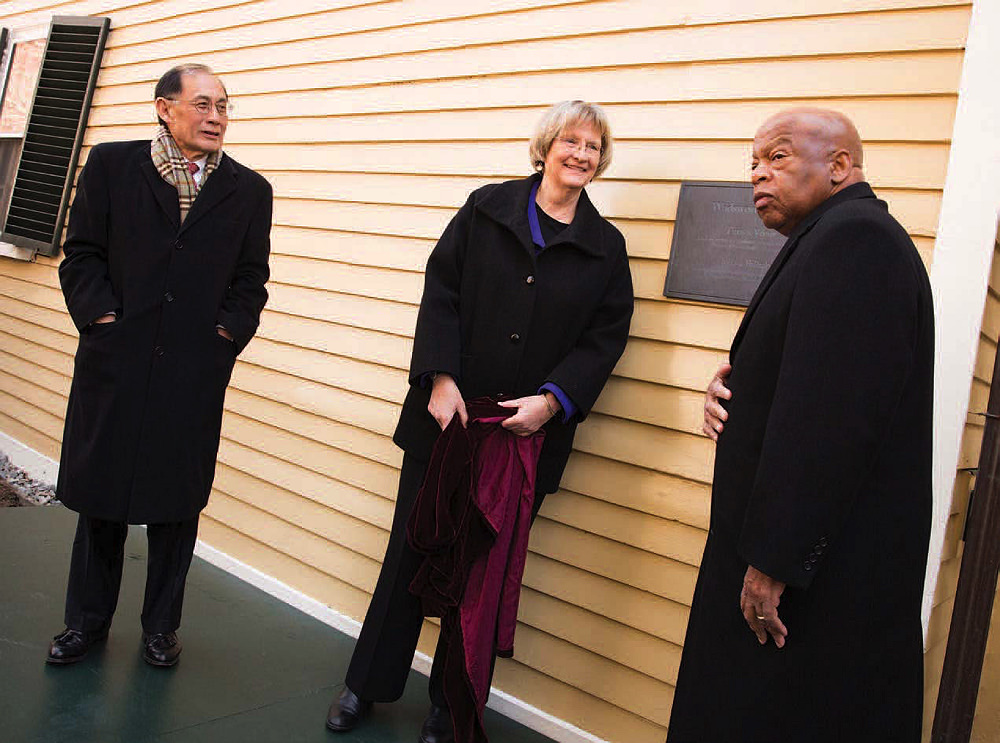

Twenty-eighth, and first: named president, February 11, 2007, with Derek Bok

Photograph by Justin Ide/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

By then, the chief proponent of that expansive vision was no longer in place to promote it: the gap between Summers’s style and Harvard’s culture having widened irreparably, his presidency ended in June 2006, and Derek Bok returned to office for an interim year. FAS’s leadership turned over, too, after Summers forced out his own decanal appointee, William C. Kirby; Bok persuaded former dean Jeremy R. Knowles to make a return to University Hall until illness forced Knowles to step away again in April 2007, and David Pilbeam filled in.

For Faust, the first order of business seemed clear: to move beyond the leadership tensions and turmoil, assembling a team able to identify Harvard’s interests and eager to pursue them harmoniously. Given the fortunate circumstances, with the right people and plans in place, the opportunities to make the world’s greatest university even greater seemed limitless.

Fast Start

Drew Faust is personally warm and gracious, and professionally a top-tier historian, who views the world in its evolving context. This past spring semester, when a visitor called to discuss her administration, the president, as is her custom, met her guest at the reception lobby in Massachusetts Hall and escorted him down the hall to her office. En route, one of her priorities was on display: the corridor is now a gallery of student art, highlighting her focus on bringing artmaking and performance into the curriculum (alongside robust extracurriculars and Harvard’s traditional, academic focus on art history and scholarly analysis of music).

Once seated, the historian came to the fore. Faust had exhumed from her personal archive a foundational document: a wire-bound notebook from the spring of 2007 (with a suitably red cover) in which she had outlined priorities for her nascent presidency. The items ranged from the customary transition matters (fill vacant deanships in medicine, design, and the Radcliffe Institute) to administrative innovations (hire an executive vice president to address human resources, finance, and so on) to looming ambitions (test, with the deans, a financial-aid fundraising initiative; hire a vice president for alumni affairs and development to begin to assess “readiness” for a capital campaign). Many of the distinctive academic and managerial matters that Faust especially emphasized—drawing from her experience as Radcliffe dean, and from her interactions with the Corporation during the presidential search—were prefigured in her clear hand, too, and would, in time, carry through her 11-year administration. Among them:

- initiate University-wide academic planning, “with an eye to campaign and Allston issues” and beyond, to articulate priorities and resources for the institution, and for boundary-crossing efforts emerging in science and social science;

- support FAS as it rolls out General Education, and in improving pedagogy generally;

- “move Allston to a new phase of action,” beginning with construction of the first science complex, and “hard-headed planning,” consistent with financial realities—for the education school, a proposed art museum, and, generally, in building the case for Allston with deans and the broader community;

- “continue to stress” access in admissions to the College and the public-service-oriented professional schools; and

- inaugurate planning to “make the arts a more central aspect of Harvard’s educational identity and mission.”

With that agenda elaborated, Faust set briskly about bringing her aims into being.

The team. Early on, she assembled her team. Two appointments were to prove especially consequential: computer scientist Michael D. Smith was named FAS dean in early June, and Tamara Elliott Rogers became the alumni affairs and development vice president in October (having had those responsibilities under Faust at Radcliffe). They remained in those positions throughout Faust’s 11-year tenure. The even-tempered Smith was ideally suited for the crushing financial challenges to come, as well as a strong connection to engineering and the applied sciences—on which Harvard would focus so much of its investments and aspirations. Rogers would in time direct the largest capital campaign in higher-education history—the nearly existential importance of which was not evident in 2007.

In a change both substantive and symbolic, as Faust explained in conversation, she reflagged the Summers-era Academic Advisory Group (of which she had been a member) as the Council of Deans: a group of senior leaders who could share their schools’ perspectives, learn from one another, and, ultimately, define the University’s mission and management collectively. “My cabinet, alter ego, and leadership team,” she called it recently.

Although the president’s office sets the agenda, the council evolved, in Smith’s telling, to become a productive, engaging, and inclusive forum for diverse perspectives, candid exchanges, and conversations that continued outside formal meetings—both among the deans and with other participating senior managers like the executive vice president and the chief financial officer. Martha Minow, the Law School dean from 2009 to 2017, said that the council enabled the deans to have “honest discussion about issues in their own schools,” and at Faust’s behest, similar exchanges about University matters—from Allston to online education to the regulatory framework governing sexual assault. “It was a feature of Drew’s leadership style to be collaborative and inviting and to build a community,” Minow said, “and I think that happened in that group.” The bilateral and University-wide relationships that resulted, she said, meant that the participants became “very trusting of each other”—useful during good times, and essential during adverse ones.

At her initial summer deans’ retreat, Faust invited Lawrence University Professor Michael E. Porter, renowned for research on organizational strategy, to prompt thinking about Harvard’s strategy. How did being associated with the larger University, he asked, give their individual schools an unfair advantage in competing for the best students and scholars? The aim was to think big and broadly, about the schools, the institution, and their collective pursuit of the future.

The themes. The president gave voice to her overarching themes in her installation exercises that October. As historian, she drew upon Governor John Winthrop’s 1630 guidance for the settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, “A New Modell of Christian Charity,” twice quoting from the same passage his call to the settlers to be “knitt together, in this work, as one.…” This summons, suitable for such a ritual occasion, was perhaps also Faust’s way of addressing, for a larger audience, the importance of restoring comity and cooperation to a community riven during and after the Summers presidency.

During her leaderly baptism, Faust had ushered Radcliffe from legacy status as a college to its life as an institute for advanced study, jettisoning old programs and forming new ones. Invoking that kind of transition-based-on-tradition in her address, she defined universities as “uniquely accountable to the past and to the future—not simply, or even primarily, to the present”—a resonant message for the first woman to preside over a 371-year-old place. (Years later, in retrospect, she repeatedly noted that the future was then becoming very imminent: the pace of technological change manifested itself with the January 2007 announcement of the iPhone, just as the Corporation was concluding its search.)

“A university looks both backwards and forwards in ways that must—and even ought to—conflict with a public’s immediate concerns and demands,” she said. As “stewards of living tradition,” she continued, universities “make commitments to the timeless,” endeavors pursued “because they define what has, over centuries, made us human, not because they can enhance our global competitiveness.”

But different circumstances a few years later would force Faust to devote her most urgent attention to those “immediate concerns.” She would also move engineering and related fields, with their relevance to “global competitiveness,” higher on the academic agenda. But her sense of the sweep of history, and of the humanizing aims and effects of higher education, would never ebb.

Nor would her sense of who, alongside her, belongs at contemporary Harvard—no matter what blinders the institution had worn a few hundred years, or even a few decades, earlier. Among those she chose to feature at the installation were historian John Hope Franklin, Ph.D. ’41, LL.D. ’81, novelist and Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, Litt.D. ’89, and artist Kara Walker (on whose Civil War work, exhibited at the Fogg, Faust gave a gallery talk a few weeks later).

The program. People in place, tone set, Faust established an ambitious menu of concrete aims around which the University could rally, and fundraisers could test the waters.

Even before her installation, the division of engineering and applied sciences celebrated its transformation into a school (SEAS), an indication of burgeoning research opportunities and student interest in those fields.

On November 1, pursuing her arts agenda, she chartered a University task force, chaired by Cogan University Professor Stephen Greenblatt, to explore investments in teaching about and supporting creativity, performance, and artistic practice.

Six weeks later, turning to access, she unveiled a major enhancement of undergraduate financial aid, putting in place an income-based standard that scaled families’ term bills from 1 percent to 10 percent of income, extending up to incomes of $180,000 (Harvard remained free for families with incomes of $60,000 or less) and eliminating loans and excluding home equity from aid calculations. The initial cost, from FAS and University funds, was estimated at an additional $22 million per year. (Graduate students’ stipends and other support had been boosted a few days earlier.)

The following spring, FAS set about planning renovation of the undergraduate Houses—a massive project that would ultimately evolve into its largest, most costly construction program. In April, Faust charged another task force with planning “common spaces” that could bring the community together socially and intellectually. And as of that June 30, the Harvard Art Museums planned to begin decommissioning the Fogg for its wholesale overhaul and expansion. Site work on the four-building “first science” complex in Allston, begun in 2007, was succeeded by excavation and heavy construction for its enormous, multistory foundations. Each prospective project would ripple across much of the University.

Each of these initiatives also entailed at least a nine-figure price tag (House renewal, the Allston complex that will house part of SEAS in 2020, and endowing financial aid across the University have become billion-dollar-plus-items): plenty for the fundraisers to discuss with prospective donors. Nor did that exhaust the shopping list: the leadership transition in mid decade had set back Harvard’s development calendar, and every school had other deferred, big-ticket requests—for facilities, faculty positions, and more. The formative steps toward a formidable campaign, tied to the academic planning and University perspective Faust sought to inculcate, were clearly under way.

The Reckoning

In any realm, leaders know that not everything goes according to plan. Harvard had learned that, most recently, in the foreshortened Summers presidency.

In August 2007, Harvard Management Company (HMC) reported a blistering 23 percent investment return, raising the endowment’s value $5.7 billion after distributions to fund the schools. Three weeks later, its newish president and CEO, Mohamed El-Erian, a Summers appointee who arrived in February 2006, announced that he would return to his former employer in California—another vacancy to fill. The same month, the Corporation gently tugged on the reins, deferring plans for a second art museum in Allston while the Fogg began its overdue, massive makeover; the Fellows and Faust apparently agreed that there were plenty of projects to manage, priorities to be sorted out by her impending arts task force, and uncertainties about paying for everything.

But those fair-weather clouds barely marred the sunny outlook. Through June 2008, the end of the University’s fiscal year and Faust’s first presidential year, HMC’s investment managers turned in an 8.6 percent rate of return (yielding a five-year annualized rate of return of 17.6 percent), boosting the endowment’s value to a record $36.9 billion—doubly impressive given that the share of the operating budget from endowment distributions had risen sharply, from 27.6 percent of Harvard revenue at the end of the Rudenstine administration to 34.5 percent of the much larger budget in 2008.

And then the world collapsed. The financial crisis and ensuing “Great Recession” ushered in severe challenges for which almost no one had prepared. On December 2, 2008, Faust and executive vice president Ed Forst, a Goldman Sachs alumnus, disclosed that the endowment’s value had declined 22 percent through October 31—and “even that sobering figure is unlikely to capture the full extent of actual losses for this period, because it does not reflect fully updated valuations” for certain assets. Because endowment distributions had far outstripped tuition and sponsored-research revenues, “The numbers may seem abstract, but their consequences are real,” this magazine reported, in an article titled “Harder Times.” Indeed: by itself, a 22 percent devaluation of the endowment implied, over time, an annual shortfall of as much as $400 million in funds for deans’ budgets.

It is instructive to take stock of the University’s predicament in historical perspective, not just as it unfolded then. In hindsight, during the early-millennium era of irrational exuberance, Harvard had been very exuberant. In 2004, it entered into swap agreements meant to hedge against rising interest rates on the huge borrowing it might undertake to fast-track Allston development. The appreciating endowment, and the cash it threw off to support operations, apparently emboldened other kinds of leverage. Most of the University’s operating funds (the central repository for tuition payments, for example—in effect, its checking account) were invested alongside illiquid endowment assets, which were yielding those bubbly returns. Straining to keep up with the robust cash flows of mid decade, HMC committed to make $11 billion available in the future for outside investors to manage. Early in 2008, Senator Charles Grassley of Iowa mused aloud about requiring wealthy universities to spend more of their endowments and rein in tuition (an issue that would reverberate in 2017). In response, a University officer suggested Harvard could easily use twice the endowment it had to support its aspirations—in a spirit that suggested attaining such riches was feasible.

As FAS incurred hundreds of millions of dollars of debt to build its new labs (University borrowings rose from $2.2 billion in fiscal 2003 to $4.1 billion in 2008, before the crash), its operations had levered up, too: those new professors’ salaries, space, and research; and the more generous financial aid (which would grow further as the recession drained family incomes). Elsewhere, the Allston science complex was sopping up hundreds of millions of borrowed dollars, with perhaps a billion dollars more to be tapped. The art museum was ready for reconstruction, and a large law school facility was under way (together, costing perhaps $600 million to $700 million).

Not all of these vulnerabilities, nor their intersecting implications, were widely evident. In the early fall of 2008, Faust said recently, “Things started unraveling fast,” and by mid October, Harvard faced “dire straits” that no one had imagined. A full-blown crisis was at hand—the defining one of her presidency.

Lacking other good options, and perhaps perceiving more grim news to come, Harvard’s financial team in December 2008 arranged to borrow $2.5 billion at the relatively high rates then available, knowing that the University would face additional debt-service costs even as revenues shrank; it needed the money. (Interest expense more than doubled from fiscal 2008 to a peak of $296 million in fiscal 2011—a painful reminder of dues to the past.)

It was one thing to “knitt together” a community little accustomed to fiscal constraint, but utterly another to introduce real limits to growth. Two events provided the most tangible evidence of the new order. Faust’s arts task force presented its report—calling for new degree programs and facilities, premised on “substantial fund-raising”—eight days after she and Forst made their sobering announcement. She and Greenblatt expressed the hope that the economic downturn would be short-lived, clearing a path toward effecting its recommendations—but there would be no immediate relief.

And in February 2009, Faust said Harvard would bring the foundation on the Allston science center—the emblem of University aspirations—up to the surface, but then defer purchases of materials to build the laboratories it would support. An ensuing review would determine whether construction could proceed; the facility would be reconfigured to save costs; or the project would have to be paused completely. The following December came the inevitable decision to halt construction—and to explore whether it could proceed with a co-developer. More ominously, she said the entire Allston enterprise would be reevaluated, with an eye toward drafting a reconceived master plan in 2012, covering just the next decade.

By then, the rationale for retreating was public. The fall reports on the endowment (a negative 27.3 percent return on investments, and an $11-billion decrease in value) and the fiscal year (additional losses of $3 billion associated with those general-account assets and the interest-rate swaps) revealed the stunning damage. Instead of ever-increasing endowment distributions, the faculties could expect a sharp, swift contraction.

As Mike Smith recalled the sensation of whiplash, FAS—more exposed than most other faculties to the endowment—overnight went from “Don’t worry about money, think big” to confronting the reality that the future endowment distribution “doesn’t even support reasonable pay increases” for faculty and staff members. Assuming it continued to enlarge the faculty ranks, raise compensation, and so on, FAS envisioned a deficit of some $200 million; given untouchable expenses—sponsored research, financial aid, and servicing its $1.1-billion debt—it faced draconian reductions. Once it refrained from making those investments, the path toward a more sustainable fisc became apparent—with similar adjustments in other schools. (There were, to be sure, de facto compensation freezes, stretched-out capital projects and new academic programs, and retirement incentives and modest staffing reductions, if no wholesale layoffs.) As an FAS administrator put it this spring, “It’s been a tough 10 years.”

Compounding the pain, external conditions made it impossible for a capital campaign, on which Faust’s initiatives had been premised, to proceed on schedule.

Having been blindsided, and left with a very bare cupboard, she set about putting the house in order. Twentieth-century financial practices were supplanted by consolidated multiyear budgets and routine reporting procedures, Harvard-wide planning for capital projects, much stricter hurdles for funding projects, and changes in accounting so schools depreciated facilities appropriately. Such management disciplines weren’t newsworthy, but their absence had contributed to the financial crisis; bearing the cost of putting them in place is part of running the institution responsibly. Operating changes included consolidation of information technology and the libraries’ back offices. Not all these measures were painless: Provost Alan Garber, often the bearer of such news, had tough FAS faculty meetings when he announced changes in the libraries and staffing consolidations; undergraduates lamented the loss of hot breakfasts (though perhaps too few of them partook to make an effective counter-constituency).

The Rebound

As she addressed Harvard’s plumbing, Faust—making virtue of necessity—began pursuing two initiatives that will likely define her administration.

The impossible one came first. In late 2009, she disclosed that the Corporation (including the president) had begun to examine University governance—a 360-year-old edifice—so that the then-seven-member Corporation could better exercise its fiduciary responsibilities and organize itself to provide strategic guidance to the institution’s leaders: in other words, to pull back from assuming unrecognized, existential financial risks and move decisively toward some more predictable, productive governance appropriate to a complex, multibillion-dollar, twenty-first-century enterprise. Though she had envisioned administrative streamlining before she became president, Faust recently stressed, the vulnerabilities exposed in 2008 prompted governance reform.

The announcement on December 6, 2010, that the Corporation would be modernized—by enlarging its membership to 13, with more diverse, broader expertise; by forming standing committees pertinent to its fundamental responsibilities; and by introducing new procedures to improve self-governance and enhance its access to critical information—was of fundamental importance. It was Harvard’s recognition that the leadership and financial upheavals of the decade then ending had structural causes that had to be addressed. Although the full impact of the changes will come into view only over decades—as the Corporation’s membership changes, as it refines Harvard’s strategy and oversees policy, and as it manages presidential successions—the effort itself seems certain to rank high among the legacies from the Faust era.

The tasks for which the reformed Corporation organized itself mapped on to similar, simultaneous changes in Harvard’s financial management, policies, and procedures. Together, they made it possible, for instance, to synch HMC’s investment guidelines and decisions with the University’s needs for cash and its capital structure, in a way that aligns with the Corporation’s strategic deliberations and guidance. Very much related to those priorities, a new Corporation-Overseers committee on alumni affairs and development pointed to the centrality of philanthropic support; and the added members of the governing board included some individuals with private-equity and venture-capital backgrounds and extensive ties to the financial industry. (Faust herself, perhaps with a nod to campaign outreach, set an apparent precedent for a sitting Harvard leader by joining the board of Staples Inc., deeply rooted in Boston’s financial and alumni communities, in April 2012.) A few of her new Corporation colleagues brought to the board a notable zest for high-stakes fundraising.

And so to the second defining initiative. As the financial crisis abated and Harvard tightened its belt, campaign planning resumed, informed by the new realities: “We were sobered about the fundamental needs of the institution,” Faust said recently—for instance, sustaining financial aid for economically stressed families. (In fiscal 2011, when FAS was most constrained, its net tuition and fees—its largest source of unrestricted cash for operations and new programs—declined, even with a higher term bill, as aid costs rose more quickly: raising the worrisome problem of eating the seed corn.)

Consistent with her goal of fostering Harvard’s collective identity and use of its resources, Faust enlisted Reid professor of law Howell Jackson to define University priorities. Jackson, who had worked on his school’s financial plans, had served as interim dean before Martha Minow, so he was familiar with the Council of Deans. For two years, he spent half his time at Mass Hall, seeing to it that overarching priorities (Allston, teaching innovation, the arts) aligned with schools’ aims, and helping connect units that had common interests in fields like global health. Melding perspectives as diverse as those of the art museums and the bench scientists, he said recently, he was impressed by their degree of cooperation and faculty members’ interest in collaborating. (Jackson himself has taught at the Business School and the Kennedy School.) The campaign’s broad success in funding both the University and school goals, he said, reflects this One Harvard approach Faust pursued from the outset.

"At Harvard..." launching the campaign, and a memorable tag line, September 21, 2013

Photograph by Kris snibbe/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

The Harvard Campaign, begun quietly in 2011 and announced with raucous celebration on September 21, 2013, sought the formidable goal of $6.5 billion. In a memorable kickoff speech, Faust deftly invoked the memory of long-time men’s crew coach Harry Parker—the icon of the energetic team player—and crafted a rousing “At Harvard…” peroration. The aims were broad—financial aid, buildings, flexible funds, and so on (academic programs were never detailed in a promised case statement)—but donors didn’t seem to mind: after 17 globetrotting Faust-led “Your Harvard” events (from Beijing and Berlin to Boston) and countless thousands of meetings and calls and solicitations, some $9.1 billion had been tallied as of the private campus celebration with donors this past April 14.

Tangible benefits abound: the Kennedy School’s reshaped campus; new executive-education and conference facilities at the business school—and broadened field-learning experiences for M.B.A. candidates; landmark naming gifts for the public-health and engineering schools’ endowments; substantial growth in the computer-science faculty; more clinical programs, and more public-service funding, for the J.D.s-to-be; a refreshed hockey rink and basketball arena; experiments in educational innovation online and on campus; partial and whole-House renovations at Quincy, Leverett, Dunster, Winthrop, and now Lowell, with Adams on deck; and common spaces like the Science Center plaza and, opening this fall, Smith Campus Center (né Holyoke). Earlier benefactions yielded the remade Harvard Art Museums, and a major bioengineering program.

The principal focus of academic expansion traces back to the 2007 reflagging of engineering and applied sciences: the FAS campaign sought some $450 million for SEAS faculty, fellowships, and research; and the University aimed to raise the $1 billion or so required to rehouse about half of the expanding school faculty in its new Allston research and teaching complex. That destination was itself a campaign surprise; under the 2012 refreshed master plan for Allston, the facility was still designated for health and life sciences—until the provost in the 2013 spring semester told the faculty that a redesigned, somewhat smaller project would accommodate the burgeoning SEAS: the anchor for an “innovation” district near new entrepreneurship centers, and across the street from the business school’s budding CEOs. (No naming campaign gift for the building has been disclosed, so the construction presumably proceeds using University funds and fresh borrowing.)

Still, for all the dollars raised and buildings built or spiffed up, the campaign may be defined less by new academic programs or faculty expansion than by its role in repairing the University’s balance sheet. Raising more than $1 billion to endow financial aid, for instance, made it easier to fulfill prior promises and to cope with escalating costs; that gives deans leeway to use future tuition revenue to invest in emerging research. Similarly, as FAS sought half a billion dollars for research, graduate fellowships, and professorships, nearly all the latter were to endow existing positions—again, freeing resources as new academic priorities arise. House renewal represented what was, after all, deferred maintenance.

Nonetheless, by being extremely creative, as Faust put it, and bootstrapping resources, the University was able to make down payments on some initiatives: an undergraduate concentration in theater, dance, and media (an element of the hoped-for arts curriculum); a nascent Harvard program in data science, and an FAS initiative on inequality in America; and grants for research, where gifts permit, on the environment and international projects. So far, most lack the trappings of academic permanency: regular faculty appointments (adjuncts, postdocs, and visiting teachers are common); and secure, sustained funding. Faust acknowledged that in an era of limited faculty growth, this flexible model has predominated. FAS’s Smith has described these ventures somewhat differently: as start-ups, to be put on more substantial footing as professors gain experience in a field, define Harvard’s distinctive approach, and then attract more lasting donor and sponsored-research support.

In this sense, Faust and deans like Smith deserve plenty of credit. For all the excitement of cutting ribbons and fulfilling professors’ dreams, they have, to a considerable extent, committed themselves to the essential work of paying for past promises—righting the institution at a truly dire moment. Through budget discipline and changed expectations, they have also helped to defend Harvard against new uncertainties, as federal research support, tuition income, and endowment returns all appear less dependable than a decade ago. (Faust and successive University treasurers and chief financial officers have repeatedly sounded this concern about universities’ business model in their annual financial reports.)

So far, Congress has rejected President Donald Trump’s proposal to slash research outlays (although huge federal deficits loom), and tuition rates have been increasing about 3 percent annually. But the persistent shortfall in endowment performance—2 to 3 percentage points below HMC’s 8 percent annual return goal in the decade from El-Erian’s departure through Faust’s successor appointees, Jane Mendillo and Stephen Blyth—has upended Harvard’s finances. At its fiscal 2017 value of $37.1 billion, the endowment was slightly above the nominal total in 2008—but billions of dollars less, adjusted for inflation. From fiscal 2007, endowment distributions have come to contribute 36 percent of University revenue: a higher proportion than a decade ago, while expenditures grew $1.8 billion (58 percent).

A capital campaign is somewhat of a misnomer. Through fiscal 2017, with more than $8 billion in gifts and pledges, Harvard’s campaign had raised more for current use ($2.4 billion, largely spent as received) than for endowment ($2.3 billion)—and other proceeds are also either spent (sponsored research) or increase operating costs (buildings). Thus, even after FAS has raised more than $3 billion, with the distribution held flat during the year just ended, the faculty finds itself again expecting a deficit, and resorting to financial engineering and additional borrowing to sustain House renewal. N. P. Narvekar, HMC’s president and CEO since late 2016, is overhauling the organization and assets, but projects a five-year transition to sounder results.

All this points to continuing items on the agenda of Harvard’s twenty-ninth president, Lawrence S. Bacow. The treasurer, CFO, and new president will pay close attention to HMC’s progress from their perch on its board. Friends of the University can expect to hear about opportunities to support the nascent research initiatives and bolster biomedical research and neuroscience, renovate the economists’ outmoded quarters, repurpose the buildings SEAS will vacate, and so on. And talk about constraining costs can be expected to persist—perhaps the biggest shift from the Harvard culture Faust inherited.

The Crowded Agenda

The financial crisis in 2008 forced the president and her administration, the deans, and their schools to make wholesale changes in policies, operations, and expectations. Nor were those the only alterations in the agenda she outlined in 2007; in conversation, Faust alluded to the sheer number of challenges that demanded attention, almost daily. Among the myriad priorities that emerged during her tenure, these stand out:

The U.S. policy prohibiting military service by openly gay personnel (“don’t ask, don’t tell”) was repealed in late 2010. The following March, Faust announced that Harvard would welcome the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps back to campus, the first such program to be formally recognized in nearly 40 years. The annual officers’ commissioning ceremony on May 25, 2011, with four cadets, was the first following the restoration of recognized status.

Sustainability. Like other universities, Harvard has made extensive commitments to control its contribution to global warming. The initial goal—reducing emissions 30 percent from a 2006 baseline, taking campus growth into account—was realized in 2016; the new goal is to be fossil-fuel-free by 2050. Those programs attracted broad support.

But student and faculty advocacy for divestment from investments in fossil-fuel companies prompted sharp disagreement, locally and on other campuses. When student activists surprised Faust with questions about the issue in Harvard Yard in 2014, she objected to their edited presentation of her views, and denounced their subsequent blockade of Mass Hall. At the next FAS meeting, she said would engage with faculty members on the issue on a basis of “reason, rigor, respect, and truth.” The Corporation held to its social-investing guidelines, refusing to embrace divestment—most directly in the form of correspondence on the subject from senior fellow William F. Lee.

A “climate-change solutions fund” has, so far, provided $4 million in grants (a favorite Faust-era tool in lieu of permanent, fixed-cost investments) to 31 faculty teams for everything from policy research to fossil-free fiction.

Sexual assault. Rising concern among students, and society at large (underscored by survey evidence of extensive harassment, assault, and inappropriate behavior), and new requirements under Title IX disseminated by President Barack Obama’s Department of Education, led Harvard and other schools to increase education, encourage incident reporting, and adopt new procedures for hearing cases. The 2016 news that the men’s soccer team had evaluated women players in explicitly sexual terms revealed the breadth of such attitudes, and the need to sustain efforts to improve behavior; the team’s season was suspended as it prepared to compete for an Ivy League championship. News accounts of apparently persistent sexual harassment by a tenured professor, resulting in the imposition of administrative leave by FAS and his subsequent decision to retire this spring, underscored the deeply rooted, continuing challenges of limiting harassment and assault.

Academic misconduct. The 2012 news that dozens of students had, deliberately or inadvertently, violated rules on collaborating on atake-home final exam prompted extensive FAS debate: about how technology is changing coursework; professors’ guidance on academic expectations; and evolving student norms. Faust largely devolved the issue to the College and faculty, albeit continuing to comment in FAS meetings and allude to academic integrity in formal addresses to incoming freshmen, for example. (When the news broke, an administration official privately pointed to the prevalence of cheating on other campuses—something of a diversion from the standards to which Harvard presumably holds its elite students.) The faculty encouraged teachers to be explicit about the rules for their courses, and ultimately instituted a formal honor code—with cases of alleged misconduct to be heard by a separate honor council, apart from the general disciplinary process overseen by the Administrative Board. Those instruments are not infallible, of course, as a recent recurrence of cases arising from the most popular computer science course attests. An unexpected casualty of the controversy was College dean Evelynn Hammonds, who pursued news leaks about the investigation by authorizing examination of email traffic from certain House officers; her departure was announced just before Commencement 2013. The faculty’s sharp reaction to the disclosure prompted Faust to institute new University standards for the privacy and security of electronic communications.

Slave connections. As student and faculty researchers probed Harvard’s history, they uncovered multiple ties to slavery. Faust, an historian of the American South and Civil War, underwrote publication of their findings. She then focused community attention on this chapter of the University’s past at an April 6, 2016, event—featuring U.S. Representative John R. Lewis, LL.D. ’12, the civil-rights leader—at which a plaque acknowledging the enslaved members of the households of presidents Benjamin Wadsworth and Edward Holyoke was affixed to Wadsworth House. She has supported further focus on the topic, including a 2017 Radcliffe conference. Faust has highlighted her personal concern about the continuing legacy of slavery and racial division by talking about her undergraduate decision to participate in the second march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama (Lewis had been grievously injured in the original march); returning for the fiftieth-anniversary observance of those pivotal demonstrations; and inviting Lewis to be the guest speaker at Commencement this May—her last as president.

Acknowledging a slave-owning past: with William F. Lee and Representative John R. Lewis, April 6, 2016

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

Academics I: General Education. One priority on Faust’s 2007 list was to work with Michael Smith in implementing the new Gen Ed curriculum, enacted during the Bok interim year, after protracted faculty debate. In hindsight, the faculty concluded during its 2015-2016 review that the rollout of the program (the principal requirement imposed on undergraduates, intended to be the broadening keystone of liberal arts at Harvard) had been muffed. During the straitened years at the end of the prior decade, course development lagged, and hundreds of departmental classes were granted Gen Ed credit, diluting its meaning to the vanishing point. Gen Ed 2.0, adopted in 2016, halves the number of courses, adds a distribution requirement, and envisions a new “working with data” class. Implementation is now scheduled for 2019—a decade and a half after the Core Curriculum was declared obsolete—and so will await a successor president, FAS dean, and dean of undergraduate education.

Academics II: Shifting student and faculty interests. Although Harvard’s intellectual capital has not grown substantially of late when judged by its number of professors, it is not the same faculty that was in place when Faust took office. On September 1, 2007, of 709 FAS ladder-faculty members, 29.3 percent were in arts and humanities (208), 34.3 percent in social sciences (243), and 36.4 percent in sciences, engineering, and applied sciences (258). A decade later, the proportions were, respectively, 27.2 percent, 32.9 percent, and 39.9 percent of a slightly larger cohort (738). Those proportions understate the largest shift: SEAS’s ranks are up nearly 30 percent since it became a school in Faust’s inaugural fall. (Smith noted that computer science is much stronger, thanks to a campaign gift. Consistent with the arts initiative, the music faculty has added a trio of performance professors, a departure from Harvard’s tradition, Faust joked, of being a place where “music is seen but not heard.”) Some of the professors have reached worldwide “classrooms” through HarvardX and the edX online-learning collaboration with MIT; and almost all have been invited to enhance their pedagogies by engaging with the campaign-funded Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching.

The bigger shift has come from students. Led by the stampede into computer science and applied math, the number of undergraduate SEAS concentrators has more than tripled, from 291 (6 percent of declared concentrators) in the school’s founding academic year to 1,013 now (one-fifth of the total). Harvard has encouraged the shift with its embrace of an innovation mantra, the iLab and its funding competitions for winning entrepreneurs, pertinent College courses, and more. The symbolic apotheosis of this shift was, perhaps, the honorary degree conferred on Facebook founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg ’07, the guest Commencement speaker last year.

The slight decline in arts and humanities faculty positions during Faust’s presidency explains some of the anxieties afflicting those fields—a sense of angst she has acknowledged, even as all concerned wonder what to do about it. The tectonic change in student interests perhaps weighs even more heavily. In her April 14 Harvard Campaign address, she reprised her theme on the enduring importance of the humanities and, alluding to the reassessment of Facebook and other social media since Zuckerberg’s speech, observed that “We have seen in the press in recent weeks vivid examples of how the remarkable breakthroughs of science and technology require us to ask broader questions about society, culture, and the responsibilities of government. Privacy issues raised by the digital revolution cannot be answered by technology alone.”

The policy context. The nation’s political environment has become more threatening to private higher education and universities, with wide public doubt about their cost and value. Faust and peers have fought hard, with success, to sustain the flow of federal research dollars. But the new excise tax on endowments was a major defeat—a sign of partisan hostility to elite schools. That, and politicking about undocumented students, immigration, foreign students’ access to U.S. institutions, financial aid, and affirmative action and admissions (the subject of continuing litigation), have made the president a frequent flier to Washington, D.C., added plenty to the general counsel’s workload, and pushed legislative briefings to the top of Faust’s remarks at many recent faculty meetings. So serious are these concerns that they featured prominently in the announcement last February of Bacow’s selection to succeed Faust and in the president-elect’s own speech (see “Continuity and Change,” May-June, page 14).

Culture high and low. Withal, Faust has indulged in a bit of fun, exercising her prerogative to loosen up Harvard’s tone through her choice of guests for the formal occasion of Commencement—while affirming her commitment to diversity and indulging her taste for popular culture. (She has confessed to loving Breaking Bad, and became a West Wing devotee as a source of relief from financial-crisis tensions.) Besides the boyish social-media billionaire, her honorand-speakers have included J.K. Rowling, Oprah Winfrey, and Steven Spielberg. Commencement-morning throngs have come to expect edutainment interludes: trumpeter Wynton Marsalis tooting his own horn (2009); tenor Plácido Domingo serenading opera buff and Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (2011); and others. (Marsalis became a Harvard fixture, lecturing and performing on campus; he and Arts First impresario John Lithgow ’67, Ar.D. ’05, are headlining a celebration of Faust’s presidency on June 28 in Sanders Theatre.)

The Arc of Harvard History

Clearly, a defining characteristic of leading the modern university is the sheer muchness of the role: what Faust, considering the violent financial and political volatility of her presidency, summed up as “What next?” But above and beyond the incessant dailiness of the demands, during a recent conversation she conjured three narratives woven throughout her administration—not necessarily in the order that would occur to an outside observer.

“The ‘One Harvard’ theme is first,” Faust pronounced. That elaboration of the first priority in her 2007 notebook gained unexpected emphasis after the financial crisis, she said, as the University’s famously independent schools and affiliates realized they were interdependent “in ways maybe we hadn’t recognized before.”

Administrative necessities aside, academic connections have proliferated and strengthened. Undergraduates now have access to an architecture-studies track (with the Graduate School of Design, GSD), a secondary field in global health and health policy (with the medical, public-health, and other faculties), and, debuting this fall, a secondary in educational studies (with the Graduate School of Education, HGSE). Faust pointed out new ties between the Divinity School, FAS, the medical school (end-of-life issues), and even the Kennedy School (peace studies). Programs like the data-sciences initiative and the biologically inspired engineering institute deliberately cross disciplines and schools. Professorial appointments in multiple units are increasingly common. And HarvardX and the learning and teaching initiative were both conceived as University-wide ventures.

Perhaps the marquee demonstration of being what Faust recently called, with amusement, “One-Harvardy,” has arisen virtually so far, but will soon be physically present on either side of Western Avenue. Business School (HBS) dean Nitin Nohria and SEAS dean Francis J. Doyle III, who met while the latter was being recruited to Cambridge, began bringing their faculties together in 2016 to explore common research and teaching interests. In June 2017, as steelworkers began assembling the frame of SEAS’s Allston quarters, the deans unveiled a joint M.B.A.-engineering sciences degree; its first class enrolls this fall. (In 2015, Doyle and GSD dean Mohsen Mostafavi created a separate master’s degree in design engineering, which began in the fall of 2016.)

Putting resources behind these commitments, it was business-school alumnus John A. Paulson, M.B.A. ’80, whom Nohria guided toward the $400-million naming gift to SEAS: the essential endowment upon which Doyle can build his young school’s future, and its natural partnership with HBS. (One of HBS’s leading fundraising professionals also did double duty during the campaign, helping HGSE’s then-new dean James Ryan fulfill his ambitious goals. One Harvard indeed.)

Not quite e pluribus unum yet, but Harvard clearly is more connected, in ways that count for students and scholars alike, than its past reputation suggests.

Faust listed “inclusion and belonging” next—broadening the cohort of students and faculty members “that make this wonderful stew of difference and learning” and ensuring that once they are present, “their voices matter.”

By the numbers, Harvard is clearly more diverse. Applicants granted admission to the College class of 2022 were reported as 22.7 percent Asian-Americans, 15.5 percent African-Americans, 12.2 percent Latinos, 2 percent Native Americans, and 0.4 percent Native Hawaiians. First-generation students represent 17.3 percent of those admitted; and 20.3 percent of those admitted are eligible for federal Pell Grants, a common proxy for low-income status: the highest share of such students to date.

Perhaps more impressive has been the changing composition of parts of the faculty—particularly difficult to effect in an era of limited growth, given low turnover and no mandated retirement age. Within FAS, as more senior professors (historically, more white males) have responded to retirement incentives, and as searches are more carefully conducted to draw on larger candidate pools and to guard against implicit biases, the faculty ranks are clearly changing (see “Faculty Diversity” for the latest data). That has been a focus of Smith’s deanship, for which Faust saluted him this spring when discussing the news of his plan to step down.

Her appointments have broadened the possibilities Harvard might imagine, as well. Katie Lapp succeeded Forst as executive vice president. Jane Mendillo was HMC’s first woman president and CEO. Diverse deans include Nohria (a native of India) and Mostafavi (an Iranian American). Faust’s recent appointees led to a woman dean of public health (Michelle Williams) and, in her last semester, upheld the tradition of a woman at Radcliffe’s helm (Tomiko Brown-Nagin) and another at HGSE (Bridget Terry Long); all three are African American. The Corporation’s senior fellow is a Chinese American, and members apart from Faust have included four women and two African-American men. Within FAS, Smith had an African-American woman dean of the College (Hammonds), succeeded by an Indian American (Rakesh Khurana), and a woman leader for SEAS (Cherry Murray).

Faust has also spoken about diversity and inclusion repeatedly—at Morning Prayers, during addresses to freshmen, and on other official occasions. She and Khurana invested enormous political capital from early 2016 through last winter in a procedurally divisive push to sanction student membership in unrecognized single-gender social organizations (the final clubs and fraternities and sororities)—a measure finally put into effect by a Corporation vote. Of late, Faust’s commitments to diversity have extended to advocating for undocumented students and for the right of transgendered persons to serve in the military. Her interests in history and in diversity combined in the recognition of Harvard’s past engagement with slavery.

Despite these tangible and symbolic acts, building community does not always proceed smoothly: witness the 2014 “I, Too, Am Harvard” campaign by black students; law students’ successful campaign to jettison their school’s shield, associated with a slaveowner; and recent, identity-focused LatinX graduation and Black Commencement ceremonies.

Reflecting the work still to be done, Faust chartered a University task force on inclusion and belonging (co-led by Danielle Allen, the first African-American woman to hold a University Professorship). It recommended in March that Harvard undertake initiatives ranging from creating new research centers and investing an additional $10 million in faculty diversity to adopting a new last line for “Fair Harvard,” as sung at this year’s Commencement (farewell, “Puritans”: see The College Pump, July-August 2017, 68, and this issue).

Harking back to her installation guests in 2007, Faust’s choice of John Lewis as speaker this year, at this moment in the nation’s history, is an unmistakable sign of a commitment that has animated her from her girlhood in segregated Virginia, through her Bryn Mawr years in the tumultuous 1960s, and from the first moments of her presidency to its last.

Third, Faust named the frontier south of the Charles and HBS: “I feel great about getting Allston in a place where it’s just going to take off,” focused on “creativity and inventiveness”—SEAS near HBS and the three entrepreneurship labs, a planned art-making space, and more. They collectively establish what she called a presence for “the makers and doers over there.”

Other signs of progress are a commercially developed residential and retail complex, built on land leased from Harvard, and the proposed “enterprise research campus,” to the east of the SEAS complex, for which Boston has granted regulatory approval (also to be privately developed on leased Harvard property). Though there are, at present, no further known public designs for academic facilities, the University has indicated an interest in a “Gateway” academic building at North Harvard Street, and has reserved space south of the SEAS complex, on the unused portion of the huge, original foundations, for more science labs. Stay tuned.

Faust recalled freezing construction during the depths of the financial crisis as especially painful, because Allston had been held up as “such a signal of Harvard’s success and future.” Now, as her presidency was ending and the SEAS relocation in 2020 neared, it was finally possible to envision a future with “one campus with a river running through it.”

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

This magazine titled its pre-presidential profile of Drew Gilpin Faust “A Scholar in the House.” Upon assuming her new responsibilities in 2007, just after completing her book on death in the Civil War, This Republic of Suffering, she indicated that her life as a practicing historian had come to its end. But now, after planning to luxuriate in the first fall season she has ever been able to spend on Cape Cod with her husband, historian of science Charles Rosenberg, Faust admitted that she has some research projects in mind, and hopes to deploy her scholarly skills anew.

Perhaps some of the colleagues who have worked most closely with her during the past 11 years knew, even better than she knew herself, that her inner historian has only been hibernating. Saluting her on May 1, at her last regular FAS faculty meeting, Michael Smith said, “Over the past 11 years, President Faust has been steadfast in her commitment to helping us advance our mission of excellence in teaching and research. We couldn’t have asked for a stronger champion for our faculty and students, or a greater advocate for the value of the liberal arts and sciences.…[B]ecause of her leadership, Harvard today is a better place to pursue impactful, cutting-edge research; to study and grow intellectually, socially, and personally; and to feel a part of an inclusive community.”

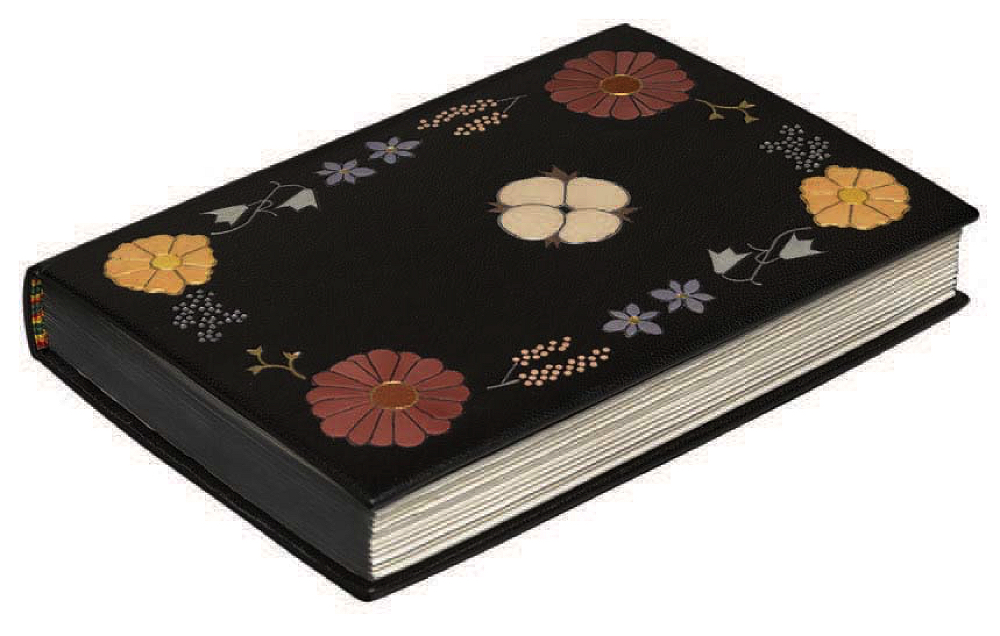

He then presented her with the faculty’s gift: a copy of This Republic of Suffering hand bound by Harvard Library’s preservation-services team, as designed by conservation technician Katherine Westermann Gray: in black leather, signifying mourning dress; with a motif of pressed flowers, “a not uncommon hobby of the time”; and a central cotton blossom, itself representing the Civil War, with four petals symbolizing the four years of conflict.

“Fittingly,” Smith concluded, “for all you have done to bring together art-making and scholarship these past 11 years, this book—your book—is now both deep scholarship and a piece of art.” He then read the accompanying inscription; it concludes, “Whether considering the legacies of our past or the promise of our future, you have inspired us to always pursue the truth.”