“Over these past few years, I have felt increasingly that something is terribly wrong—and this year ever so much more than last,” said professor of biology George Wald, who shared the 1967 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine. “But I think I know what’s the matter. I think that this whole generation of students is beset with a profound uneasiness, and I don’t think that they have yet quite defined its source.”

His speech, at an antiwar teach-in at MIT in March 1969, captured the spirit of a troubled time—an era that culminated in unprecedented upheaval on campus, and is now being recalled in the second of two fiftieth-anniversary exhibitions at Harvard University Archives.

The sources of that “uneasiness,” of course, were numerous, in a nation and on campuses polarized by the Vietnam War, political violence, riots that decimated American cities, and the radicalizing, televised confrontation between protestors and the Chicago police and National Guardsmen on the streets during the Democratic National Convention in late August 1968. A fiftieth-reunion exhibition at the archives last spring brought back to life the experiences of the class of 1968 (read about that exhibition within this longer post). As seniors, they voted to host Martin Luther King Jr. as their class day speaker; after his assassination, his widow, Coretta Scott King, agreed to speak in his place—and arrived on campus a few days after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy ’48. That spring, black students had demanded changes in admissions, the curriculum, and faculty hiring; and hundreds of students indicated that they would not serve if called to military duty. But the campus itself had not yet been torn asunder, as Columbia’s was that spring.

“We got really interested in doing this exhibition when we started doing one on 1968, and we realized that with the events of 1968, the world starts to change, and it continues to change into 1969,” said University archivist Megan Sniffin-Marinoff (Harvard Portrait, January-February). “Harvard in 1969 is as active—if not more active—on many fronts than it was in 1968”: hence the 1969 exhibition, coming this fall. It will cover both the continuing work of the University that academic year and then, ultimately, the April occupation of University Hall, the violent removal of the student protestors at the hands of State Police officers, and the chaotic days that followed on campus—one of the most shattering, shaping periods in modern Harvard history.

“We really felt that if anyone was in the position to try to put some of that time period into context,” Sniffin-Marinoff said, “we were the ones who had the documentation and could really provide as rich a picture as we can of what was going on on our campus in 1969, not just with the students but with the faculty and administration.” Amid the tumult after the University Hall bust, “Life went on, research went on, teaching went on,” she said. Accordingly, the exhibition will seek to place those events in the context of the academic work of students and professors, and of broader political developments as refracted through Harvard. Science will feature more prominently than in the 1968 exhibition, tracking faculty members’ involvement in the development of environmental regulations, the Apollo launches, and nuclear nonproliferation efforts.

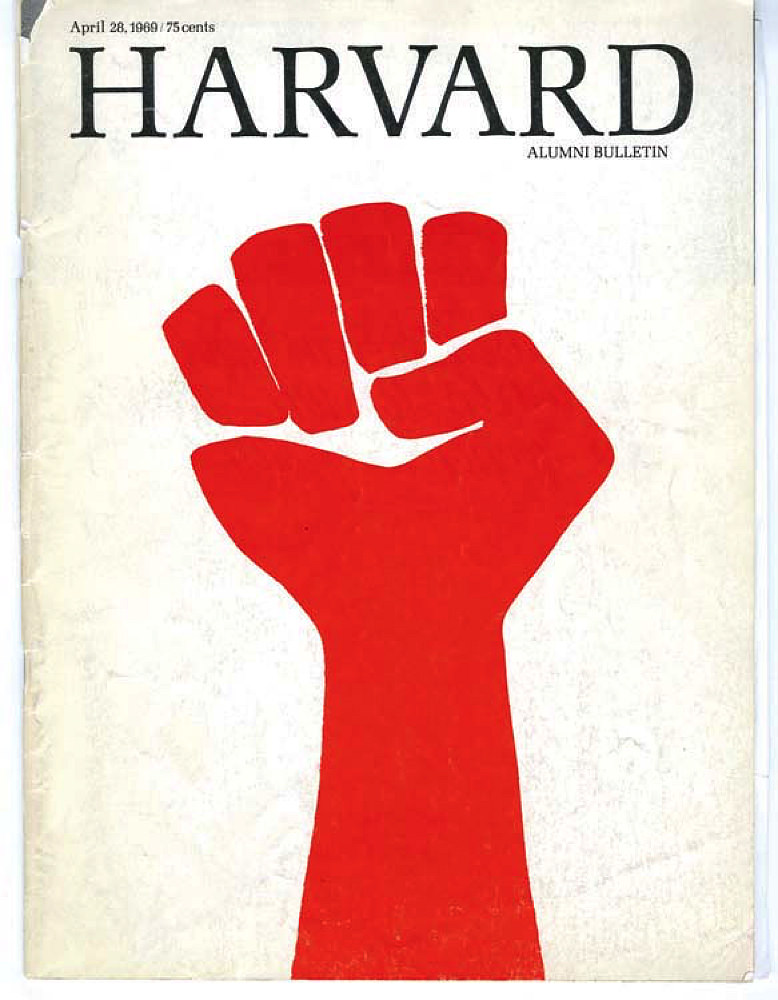

Harvey Hacker ’63, M.Arch. ’69, designed an image that became emblematic of the era: a red, clenched fist.

Magazine cover from the Harvard Magazine archive

The archives hold a wealth of resources from that period, Sniffin-Marinoff said—even more than was available for the 1968 exhibit. Posters (many produced at the Graduate School of Design, which became a de facto headquarters for protest materials in the late 1960s), press clippings from local papers, photographs, and banners will be used to recreate a “flavor,” she said, of campus life in 1969. Those relics—recording the rhetoric and the visual protest materials that student demonstrators used—help explain how national politics transformed activism at Harvard.

“We have T-shirts with the Harvard fist on it,” Sniffin-Marinoff said, “and there’s a whole history behind that, so I think we’re trying to dig a little deeper into some of the symbolism that came out of the time, and trying to understand some of the choices students made in the symbols they chose to use in the posters. Some of it may be unique to Harvard, some it may be reflecting what they’re seeing in political organizations outside of Harvard, or around the world, not just in the United States.”

Sports, too, will feature in the exhibit, which will recreate the energy from the 1968 Harvard-Yale game, when the teams concluded a nail-biting contest with a 29-29 score. Also highlighted is a lesser known episode in Harvard’s athletic history: the 1968 crew team’s participation in the Summer Olympics. “One of the things we’ll point out in the exhibit is that people often forget that intercollegiate activity was part of the Olympics,” she said. “We’re trying to show how much things have changed, the effect that strife in the world had on the Olympics, and how that bears on the crew team.” Archives retains portions of the correspondence between Harvard administrators and members of the U.S. Olympic Committee that detail arguments the parties had about the crew team’s decision to publicly decry racial discrimination in the games.

The archives will also incorporate multimedia into the exhibit, presenting short oral histories that pair alumni who discuss the era—from attempts to complete a merger with Radcliffe, to the daily ways the Vietnam War affected the campus climate. The videos are the product of a collaboration with StoryCorps, a company whose oral histories are archived in the Library of Congress.

“The upheaval had shaken Harvard to its roots, and had set it going in new and different directions,” this magazine wrote of the events of 1969. The exhibit opens in Pusey Library in November.