Five years after the founding of the Hasty Pudding Club in 1795, in the dorm room of Nymphas Hatch, A.B. 1797, the then-secret society staged its first performance: a courtroom drama in which a club member was charged with “insolence.” This proved so entertaining, the membership enshrined the practice in the club’s constitution. Later, the group began trying historical figures: Marcus Brutus, for example, was held accountable for killing Caesar. In 1837, the poet James Russell Lowell, A.B. 1838, then Pudding secretary, described the first instance of a performance in drag. The evolution continued: the first real play, its script written by a professional in England, was staged in Hollis 11 in 1844, and described in the club secretary’s records (rendered in verse as tradition required) as “…a theatrical representation/On Pudding rules an innovation/And of College regulation/A most flagrant violation.”

Image courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection

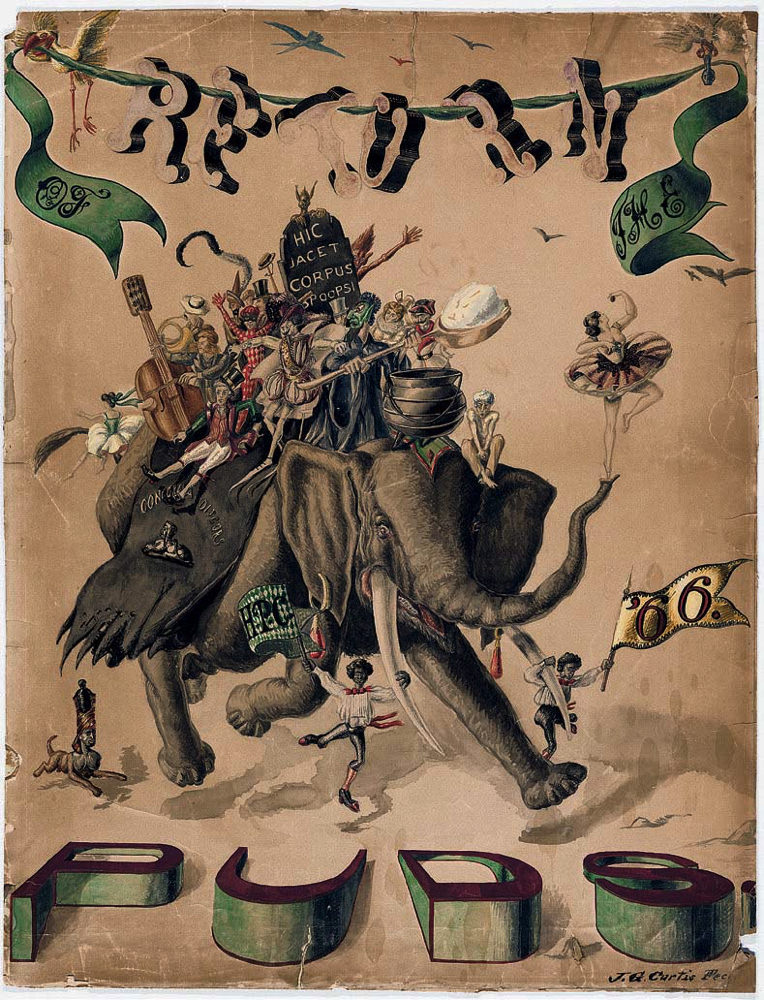

Although the plays continued to be performed for members only for another decade, the first posters celebrating the club and its performances began to appear in the years bracketing the Civil War. Harvard’s collection of this artwork, spread between the University Archives and Houghton Library, contains many unusual rarities, including the only known depiction of the College outhouse, “University minor,” that stood behind grand, granite, Bulfinch-designed University Hall. These posters, known as shingles, were hung on the walls of student rooms, and then of theaters, during performances.

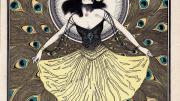

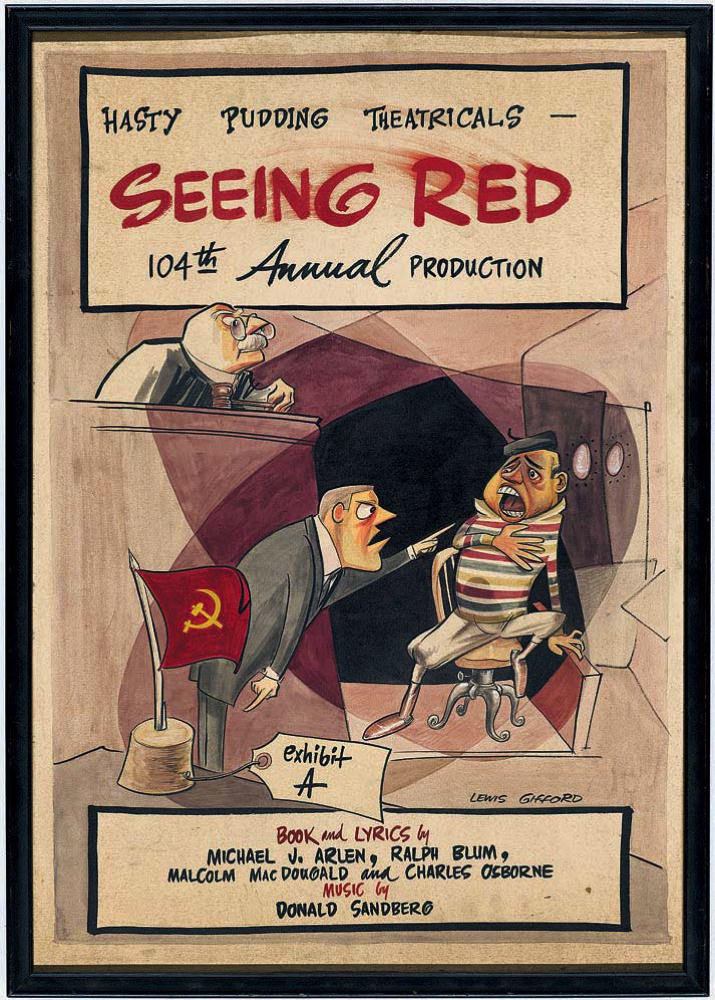

Return of the Puds, from 1866 (at left), is full of the “Oriental iconography”—from the sphinx to the alligator (the title for an officer of the club whose role is to recite poetry)—“that became part of club mythology,” says Dale Stinchcomb, assistant curator of Harvard’s Theatre Collection. Atop an elephant, the alligator serves hasty pudding from the familiar pot. The 1910 Diana’s Debut (at top), one of the most beautiful illustrations in the collection, was the cover for the musical selections from club member (and later communist) John S. Reed’s play satirizing the “coming-out” of a Boston society girl. Seeing Red (1952) spoofed McCarthyism. (Reed, A.B. 1910, a hero of the Bolshevik revolution buried in the Kremlin wall necropolis in 1920, would no doubt have approved.)

Image courtesy of the Harvard Theatre Collection

Once all-male, the club is now fully integrated, and perhaps poised to reinvent itself again. In the current era, “the novelty of a drag performance has worn off almost entirely,” Stinchcomb points out, but there will always be a need for “clever social satire.” There is no shortage of subjects.