Wearing Arab robes, grasping a rifle, the archaeologist glares out from the printed page. It might be T.E. Lawrence, but this is a very different man—not a warrior but a canny entrepreneur: Edgar J. Banks, A.B. 1893, A.M. ’94.

Views of him differ. While one scholar finds that Banks’s work “holds an important place in the history of Near Eastern field archaeology,” another labels him “huckster” and “grifter.” Both might agree that he made his mark as a seller of merchandise and that his chief product may have been himself.

Banks had been well trained in archaeology. Beyond his Harvard studies, he had a doctorate in Assyriology from the University of Breslau. Despite that background, he had only one dig to his credit, from 1903 to 1905 in what is now Iraq, work described in his book Bismya; or The Lost City of Adab. Engagingly written, it is as much a tale of exotic travel and adventure as it is of archaeology. According to its preface, it was intended to appeal “not to the scholar alone, but to the reader who is interested in days and things long passed, and especially for him has it been written.”

University of Chicago Library’s Electronic Open

The book begins with the Byzantine complexities of obtaining a permit to dig from the Ottoman authorities, a three-year process that Banks had expected to last two weeks. He describes how only 5 percent of applications are ever seen again “excepting in the form of smoke through the chimney.” His luck turned only when “an American official in Turkey was kind enough to be shot at,” thereby putting pressure on the government in Istanbul. And the permit represented just the start of difficulties. The journey to the Bismya site brought threats of desert robbers, cholera, and revolution. Eventually his excavations yielded a Sumerian city from the third millennium b.c.e. Among the thousands of artifacts he found, the star was a piece Banks announced as “the oldest statue in the world.” He transliterated the figure’s name, inscribed on its shoulder, as “Da-udu” (the equivalent of “David”), although later scholars named it, less dramatically, Lugal-dalu. The statue ultimately was his downfall when Banks was accused of attempting to send it, along with other antiquities, packed into a crate marked “honey and manna,” back to his sponsor, the University of Chicago. That was not allowed under his permit, and the statue stands today in an Istanbul museum.

Although the dig ended badly for Banks, that alone does not seem to explain the direction his career took. Rather, one gets the impression that at heart he was more of a popularizer than a scholar. He became active instead on the lecture circuit, where a brochure describes him as “an archaeologist with a happy facility of popularizing his subjects.” He wrote books for the general public such as The Bible and the Spade and The Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. In articles he portrayed himself as a man of bold exploits such as climbing Mount Ararat—which, he wrote, “in spite of the belief that the gods forbid it, has been the aim of many a traveler; few have succeeded.” Yet he also made sure that his scholarly credentials were never overlooked, laying claim in biographical sketches to writing “several hundred” articles and lecturing at “more than 200 of the leading colleges and universities.” An anonymous article (whose authorship can be traced back to Banks himself) referred to him—more than a decade after his only dig—as “the eminent explorer and archaeologist.”

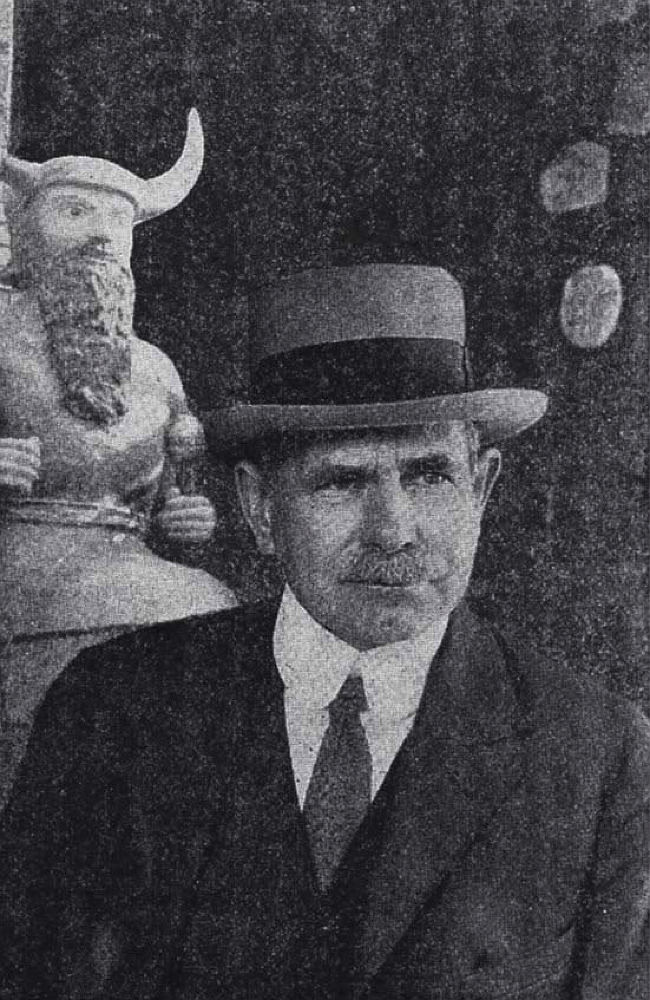

Banks, ever the popularizer, working as “research director” for Sacred Films Inc., 1922

Photograph from The Photodramatist, March 1922

In the 1920s came a foray into biblical movies, detailed in articles he wrote such as “‘How Did Sarah Dress Her Hair’: Accuracy of Detail Now Demanded by Public Brings Scientists to Aid of Producers.” The accompanying photograph of Banks carried the hyperbolic caption, “When the University of Chicago needed a leader for its Babylonian Expedition, it selected the author of this article, who is one of the world’s foremost archaeologists. He is now employing his vast technical knowledge as research director for Sacred Films, Inc.”

If Banks had a lasting impact, it came through another of his occupations: dealing in antiquities, particularly cuneiform tablets (as many as 11,000) that went to many collectors and museums. The sales were cleverly done. The letters he sent out (at least some unsolicited) began by providing his bona fides and stating that he was not just “a merchant of Babylonian antiquities.” That done, he tailored his approach to his audience. He tempted a private collector by asking if he “would care to obtain for your library or cabinet a few genuine Babylonian tablets.” To a librarian, however, he offered a piece that “should only be in a museum or school, where it may be seen and appreciated by many”—while creating a sense of urgency because “a wealthy man in Chicago wishes to purchase it, but I am not willing, if it could be avoided, that it pass into the hands of a private collector.” When asked for photographs, he sent the objects themselves instead; one imagines him thinking it would be harder for a customer to give up a treasure once actually in hand.

Many tablets were simply records of routine transactions, but one, now known as Plimpton 322 and housed at Columbia, has been characterized by an historian of science as “one of the world’s most famous ancient mathematical artefacts.” Its exact nature and purpose are still debated, but it may be the oldest known trigonometric table. Banks, unaware of its significance, had sold it to a collector for $10.

He did well enough for himself, though. His end was far more peaceful and less exciting than might be expected of someone who built his reputation on intrepid deeds. He died in Florida, the owner of an antiquities-filled mansion and 350 acres of orange groves.