The story came to him the night he became a father. Author Rudy Ruiz ’90, M.P.P. ’93, had known since college that he wanted to write a novel, but he felt like he needed more life experience first. “When the time is right,” he told himself, “the idea will come to me, and I’ll be ready.” Then, eight years after graduation, as he carried his newborn daughter to her nursery in their San Antonio home for the first time, he “had this epiphany. I knew right then the story I had to write.”

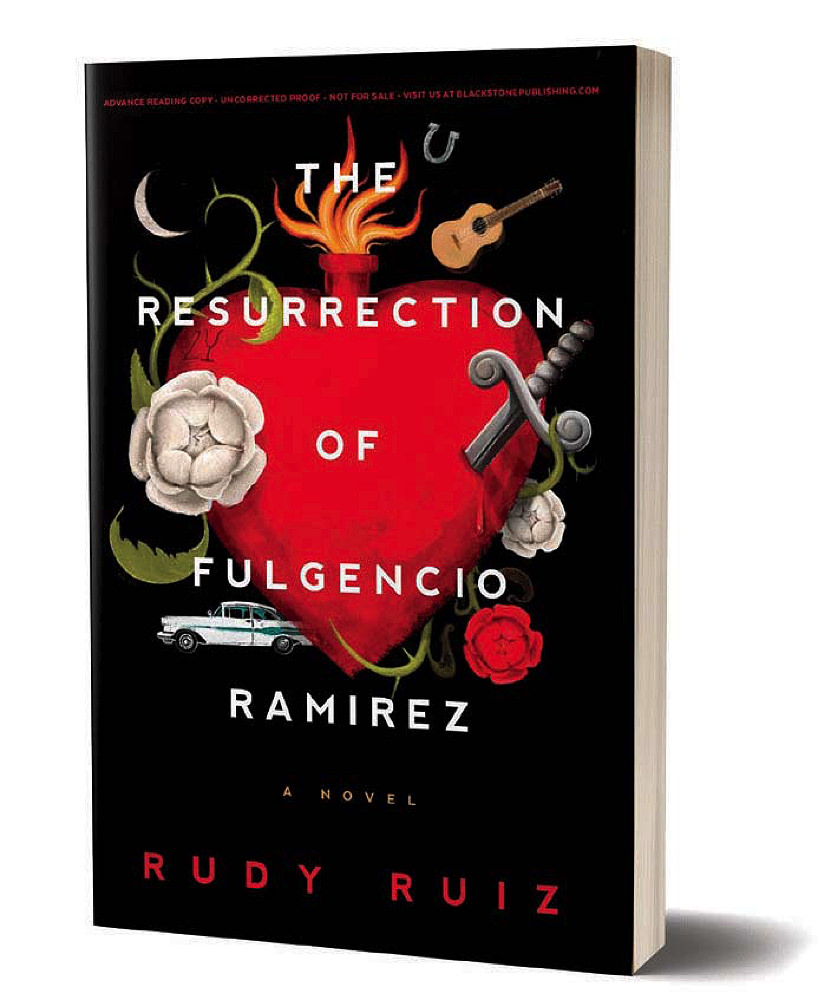

This novel, loosely based on his father’s 1950s upbringing on the U.S.-Mexico border, was published in 2020, 22 years later, as The Resurrection of Fulgencio Ramirez. It has since been honored by the American Library Association’s Booklist as one of the Top 10 best debut novels of 2020 and by the 2021 International Latino Book Awards as the best Latino-focused fiction book. “I think being a parent myself,” Ruiz said, “something suddenly clicked inside of me, and I knew I needed to build upon the stories that I’d always been told.”

Storytelling was part of the rhythm of Ruiz family gatherings. His father, a pharmacist and first-generation American, told stories of “reaching for the American Dream” (like mowing the lawn of his private high school to pay his tuition), and his maternal grandmother recounted her adolescence during the Mexican Revolution. The border loomed large in family lore, but it was also a fact of daily life. Ruiz’s childhood home in Brownsville, Texas, was bordered on one side by their neighbor Mrs. Pachecho’s orange and lime trees, and on the other, by what locals call a resaca—an oxbow lake left behind by the Rio Grande. Every day, they drove the five minutes to Matamoros, Mexico, where his extended family lived. He even relocated to Matamoros for seven years and carpooled across the border for school in Brownsville. He said, “It was a magical experience growing up in a place where you have a sense of belonging to two different countries, two different cultures, two different languages.”

Ruiz listened to his family’s stories attentively, but he started writing his own out of impatience. As a child, if he couldn’t get to the library quickly enough for a book he wanted to read, he’d write his own. First drafts have always been his favorite; he usually writes them at night “when it’s very quiet and you can get totally lost in the world you’re creating.” He follows a rough outline “to avoid any serious entanglements,” but he leaves as much room for spontaneity as possible: “I want writing to be fun, and if I already know what the whole story is going to be, down to every detail, it’s not fun, you know?”

He left Brownsville for a government concentration at Harvard College and discovered magical realism in Spanish-language literature classes. Ruiz felt his own writing freed up by the “unabashed lyrical flair, poetic style, and visual richness unafraid to be bold and colorful” of Latin American magical realism authors like Gabriel García Márquez and Isabel Allende, who infused their realistic stories with fantastical elements like ghosts or characters with supernatural powers. “I always loved reading, but after finding [magical realism], it was a much deeper, personal, almost spiritual connection,” Ruiz said. “I thought, wow, this is the kind of writing I want to do.”

The genre allowed him, he says, “to capture my family members’ larger-than-life personalities and their crazy stories and fashion a world in which they were, well, believable.” In The Resurrection of Fulgencio Ramirez, for instance, the title character, a pharmacist based on Ruiz’s father, navigates both the U.S.-Mexican border and the border between past and present, as long-dead relatives and even the Virgin of Guadalupe help him break a family curse. Like his title character, Ruiz felt his own sense of communion writing the book: “It was almost like a time machine, where I could go back and spend time with my father in this world that doesn’t really exist anymore.”

Fiction hasn’t been Ruiz’s only outlet for “bridging the cultural divide” between the United States and Mexico. As his creative-writing career developed, he also earned a master’s in public policy from the Kennedy School, and he and his wife started a marketing firm that provides “public sector, non-profit, and socially conscientious marketing for multicultural audiences.” Usually in the wee hours of the morning, he worked concurrently on various novels and immigration-themed speculative fiction, such as a short story about a post-apocalyptic future in which American citizens are the ones fleeing across the border. He also published nonfiction like ¡ADELANTE!, a combined memoir and guidebook “for immigrants in search of a better life,” and provided political commentary for CNN.com about Mexican-American issues.

Even as he sets aside op-eds to focus on fiction (his next novel debuts in September 2022), Ruiz always finds his way, one way or another, back to the border in his writing. “I almost feel like an ambassador for it. Not a lot of people know much more than what they see on the news, which presents a pretty bleak picture of the border. I love to share a fuller picture of it,” he said—one with Mrs. Pachecho’s orange and lime trees, and generations of “cross-border families,” and colorful houses on dusty streets. “If I can capture some of that experience, maybe people will reassess their opinions on the border and immigration. I know it sounds idealistic,” he said, “but hey, I am idealistic.”