Jarvis Givens remembers feeling like a door had opened in his mind. Having flown across the country on the kind of offbeat, open-ended quest that later would become a regular part of his research process, he was sitting in a church storage closet in Prince George’s County, Maryland, sorting through a stack of old documents and videos. This was the spring of 2016; he was just a few weeks away from receiving his doctorate in African diaspora studies from the University of California, Berkeley. His dissertation, on the history of black education during the era of Jim Crow, was basically done. “I’d already put closure on it,” he says. “I was just waiting for approval to file it.”

But then he received an invitation he couldn’t pass up, from a woman who belonged to an organization founded a century earlier by the historian and educator Carter G. Woodson, Ph.D. 1912. Often called the “father of black history,” Woodson and his organization—the Association for the Study of African American Life and History—were central to Givens’s dissertation. The woman, Barbara Spencer Dunn, had heard about the young scholar’s research and wanted to help. She wasn’t an academic, but for years she’d been collecting materials related to Woodson and the black teachers and students he interacted with all over the country. Maybe something in there would interest Givens?

Children learning about Thanksgiving, with model log cabin on table, Whittier Primary School, Hampton, Virginia circa 1900.

Archival photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress

And so, soon afterward, Givens found himself in the church storage closet, searching through the collected materials for…something. He figured he’d know it if he found it.

And then he did: among the videos was one recorded by a retired Washington, D.C., minister and politician named Jerry Moore, recalling a teacher he’d had as a teenager. During the 1930s, Tessie McGee had taught history at the only black secondary school in Webster Parish, Louisiana, where Moore was born and raised. By 2009, when the video was made, he was an old man, but his memory of that long-ago classroom remained clear. In particular, he described how McGee would secretly teach her students black history and culture—stories of enslavement and oppression, rebellion and escape, achievements and contributions to the modern world: concepts forbidden by the state’s all-white department of education and the local school board. While McGee and the students displayed approved outlines of the official curriculum prominently on their desks, she kept one of Woodson’s textbooks of African American history open on her lap, out of sight. She read passages from it aloud to the class, and if anyone came into the room unexpectedly, instantly switched to the outline. As soon as she and the students were alone again, her eyes would return to the book.

This scene Moore described was a revelation for Givens, a glimpse at a flesh-and-blood episode in the history he’d been examining at a greater remove in the archives. “The physical act of Tessie McGee secretly reading from the textbook was, to me, an extension of the curriculum itself, which she was writing against the grain of the dominant scripts of knowledge,” says Givens, assistant professor of education and an affiliate of the department of African and African American studies at Harvard since 2018. Beyond the forbidden material in the textbook, the lesson her students absorbed, as they watched their teacher’s careful concealment, Givens adds, was about their “shared vulnerability” as black people in the classroom—an understanding that black education was deeply political, part of a larger freedom struggle.

“Her embodiment of this kind of resistance, this counter-educational project,” Givens says, hinted at a much fuller story than the one covered in his dissertation. “This was about not just the intellectual history of black education—not just facts and dates and ‘This is what happened’—but the social history and emotional context of black teachers and black schools and the things they did to make these ideas available to students.” McGee’s quiet defiance carried real risk. She knew that if she were caught, she would likely be fired, or worse. From his research, Givens shares stories of black principals and teachers dismissed and threatened by Klan-led school boards or white superintendents. Sometimes educators were physically whipped. Between 1864 and 1876, roughly the years of Reconstruction, even before the Jim Crow regime took hold, more than 600 black schools in the South were burned. It was not uncommon, Givens says, for departures from the required curriculum to provoke violent responses.

He began calling the work that McGee and other teachers like her were doing in their classrooms “fugitive pedagogy,” a term with unmistakable echoes of the archetypal fugitive slave, who surfaced in black teachers’ underground lessons as a folk hero and cultural symbol. The connection is intentional: fugitive pedagogy, in Givens’s formulation, is the covert pursuit of black education as a means to liberation, a strategy for subverting racial subjugation. It had to be covert, he says, because it was a form of escape, a tradition bound up with the people who had once absconded from plantations. “If you can control a man’s thinking, you do not have to worry about his action,” Woodson famously wrote in The Mis-Education of the Negro in 1933, starkly clarifying the stakes. As Givens worked on his own book, Fugitive Pedagogy: Carter G. Woodson and the Art of Black Teaching, published in 2021, that same clarifying urgency rang in his ears, too—in ways that were surprising and, it turned out, deeply personal.

Fugitive Pedagogy articulates the social history that Givens envisioned writing that day he heard the story of Tessie McGee. After that first discovery, he spent years chasing down a “patchwork” of sources: public school records, teacher association archives, journals, oral histories, correspondences, eulogies—anything that might lead him to the voices of black teachers and students or bring him into classrooms like McGee’s. He searched through ephemera from long-gone black schools, the personal papers of prominent educators, and the notes and lesson plans of ordinary teachers. (This “messy” research process helped spur a further effort, The Black Teacher Archive, launched in 2020 with Princeton historian Imani Perry, J.D. ’00, Ph.D. ’00. The first phase of the project is to locate and digitize all the journals published by “Colored Teachers Associations” from the 1920s through the 1970s. “When I was seeking out these records, I realized how scattered they were,” he says, “how easily they could be lost….They’re an important resource documenting the intellectual and political legacy of black teachers, and there’s an obvious need to make sure they’re preserved.”)

In Houston, Givens found multiple drafts of a syllabus that Ira B. Bryant, a social studies teacher at Phyllis Wheatley High School in the 1930s, had developed for a curriculum in “Negro history and literature.” Givens’s research took him into the North, too, where segregation and hostility to black education were often the custom, if not the law. In Chicago, he found the records of a teacher, Madeline Stratton Morris, who, in close consultation with Woodson, put together a black history course—the first of its kind there—and made the syllabus available to other teachers who might use it. “In New Orleans,” Givens says, “you’ll find teachers who are organizing study groups to incorporate Negro life and literature into the elementary schools, the junior high, the high-school program.” Amid this constellation of documents and artifacts, “you can really see the circulation of ideas in this networked world that black teachers were a part of,” he says. Those networks made it possible for “someone like Tessie McGee, who’s in rural Louisiana, to get access to textbooks by Carter G. Woodson.”

Expansive, meticulous, and at times powerfully lyrical, Fugitive Pedagogy offers a new framework for thinking about the individual stories of black students and teachers across the Jim Crow South: not as isolated scenarios, but part of a pattern that was sustained “by black institutions and shared visions of freedom and societal transformation.” He goes on: “They were not sporadic. They were the occasion, the main event. Fugitive pedagogy is the plot at the heart of the matter—the story and the scheme.”

It is also an idea with striking contemporary resonance, at a moment when the public sphere is engulfed in fierce debates about the legacy of slavery and racism and how to teach it in schools. By the time Givens’s book appeared last April, Republican legislators in several states were considering new laws prohibiting public schools from teaching “critical race theory,” an academic (and, until recently, narrowly defined) concept developed at Harvard Law School in the 1970s, which now has become a catch-all term to describe almost any field or subject—or book, or writer, or even individual word—related to the study of race and racism. The number of states seeking to ban “critical race theory” is now more than 30, and in at least nine of them, laws are on the books. During the spring and summer, as Givens was on book tour, the news was full of angry protests by white parents at school board meetings across the country. Sometimes there were physical confrontations; often there were threats of violence against teachers and administrators.

The parallels were not lost on Givens. In The Atlantic and the Los Angeles Review of Books, he published essays drawing on his Fugitive Pedagogy research to argue that “antiracist teaching” is not a novel phenomenon, and to demonstrate “the tools African American teachers of the past left behind for us to pick up, reconfigure, and do battle with in our time.” The news site Vox ran an interview with him headlined, “Is there an uncontroversial way to teach America’s racist history?” (The short answer from Givens: not really.) And last fall, he taught a Graduate School of Education course titled “Anti-Racist Education in Global and Historical Contexts.” The syllabus included readings from South Africa, the Netherlands, and Portugal. “It was my way of responding to the current discourse,” he says. “There’s a lot we can learn from studying the longer history of anti-blackness in education, and how people have organized through institutions to name that reality and resist it.”

Givens’s colleague Brandon Terry, assistant professor of African and African American studies and social studies, sees the same kind of value in Fugitive Pedagogy. “Jarvis set out to write a definitive account of this underground insurgent practice of black teaching,” Terry says, “and in doing so, he actually ended up writing one of the books that I think will be most central, not just to the scholarly study of education history, but to the practice of resistance in the present tense. There’s no way he could have known it, but we’re in a world that looks a lot more like the one he’s describing than I think anyone anticipated when he started his dissertation research.” The son of a public-school teacher and the husband of another, Terry studies civil- rights historiography. “Jarvis shows us that to sustain something like a collective practice of fugitive pedagogy, you don’t just rely on anarchic, episodic, heroic initiative,” he says. “You’ve got to build a community around this stuff.”

In Fugitive Pedagogy, the engine of that community is Carter G. Woodson, whose life and work provide a through line illuminating the “networked world,” in Givens’s words, of black teachers. A towering figure in the history of black education, Woodson is most commonly remembered as the founder of Negro History Week, the precursor to Black History Month. A wildly successful bit of creative marketing, the initiative was launched in 1926 as a celebration of African American achievement, and by 1931, more than 80 percent of black high schools were participating.

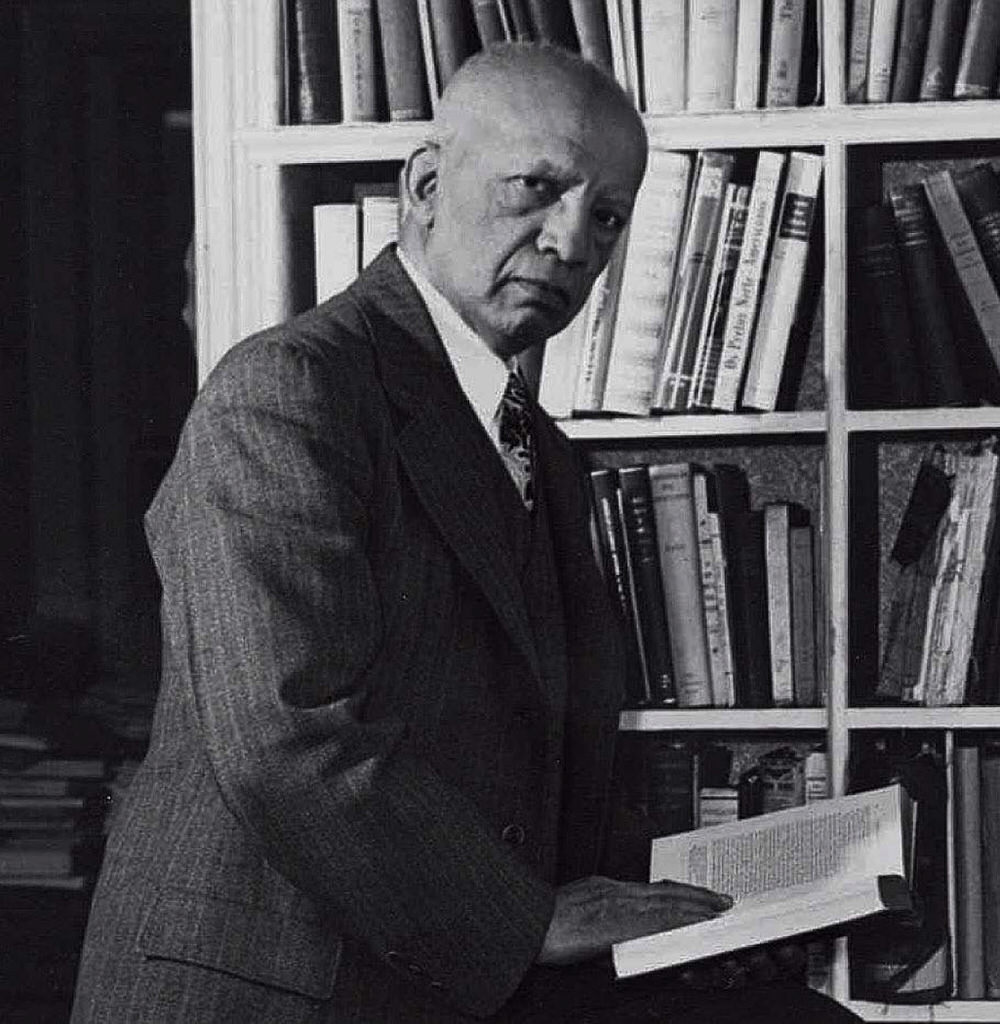

Carter G. Woodson

Photograph courtesy of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History

But Woodson’s influence was even broader and deeper than that. The second African American after W.E.B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. ’95, to earn a Ph.D. at Harvard, he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History in 1915 (ASNLH, now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History), a national forum and intellectual community that galvanized a grassroots movement. The ASNLH provided classroom decorations, posters, and instructional materials that shaped what Givens calls a “black learning aesthetic.” The Journal of Negro History and the Negro History Bulletin, both published by the ASNLH, became important channels for circulating new ideas and research, as did the press launched in 1921, Associated Publishers Inc., which published the African American historical scholarship that major white publishing houses weren’t interested in. Woodson wrote hundreds of monographs and dozens of books, including several textbooks. His paradigm-shifting The Mis-Education of the Negro remains in popular circulation, with the term “mis-education” lodged deep in black vernacular, Givens notes, as a shorthand critique of the indoctrination-through-education of white supremacist ideas.

A secondary-school teacher and headmaster for nearly 30 years, Woodson often partnered directly with teachers (including Albert N. D. Brooks, a Washington, D.C., educator and the father of Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Thomas professor of history and African and African American studies). Woodson’s speeches on the politics of black education, delivered in churches and school gymnasiums across the country, were attended by hundreds, sometimes thousands. Givens describes one hot Georgia day in 1942 when 2,500 teachers packed into a chapel to hear Woodson speak—the place was so crowded that many stood on chairs outside the windows to listen.

But the Woodson who most intrigues Givens in Fugitive Pedagogy is an earlier one, not yet larger than life: a child born in 1875 to formerly enslaved parents, a student in a one-room schoolhouse in rural Virginia, whose first teachers were his two formerly enslaved uncles. At 17, Woodson left home to find work and ended up in the coal mines of West Virginia, where he served as a reader and teacher to fellow miners, ex-slaves, some of them Civil War veterans, who were illiterate. That responsibility, and the experience of “communal literacy,” profoundly affected Woodson. “Through the stories of these former slaves, Woodson learned that black people, too, were living, breathing history,” Givens writes. “Despite their technical illiteracy, they had the capacity to read the world and speak truth to power.”

Throughout Fugitive Pedagogy, Givens traces lineages and threads of meaning that reach forward and backward in time: back to the era of slavery, when, for a black person, education was literally a crime and a slave learning to read and write was “running away with himself,” as Frederick Douglass’s master once warned. And forward to the civil-rights and Black Power movements, whose leaders often grew up in the Jim Crow South. In autobiographical materials from people like Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, L.D. ’12, James Baldwin, and Angela Davis, Givens found story after story of the black teachers who had shaped them. “These people didn’t come out of nowhere,” he says. “These stories that they’re telling and retelling in their autobiographies—there’s a sustained tradition of black teachers who were intentional about planting the seeds of these ideas in the minds of their students. We don’t get a Martin Luther King or John Lewis, or so many of the other leaders in the black freedom struggle, without the social and emotional context of these black schools.”

There is another thread in Fugitive Pedagogy, too—one that reaches directly into Givens’s own life.

“We don’t get a Martin Luther King or John Lewis, or so many of the other leaders in the black freedom struggle, without the social and emotional context of these black schools.”

It was not until college that he began to realize just how unusual his educational upbringing had been. Givens grew up in Compton, California, raised alongside a multitude of cousins in his grandmother’s home, where he and his mother lived after his father was shot and killed when Givens was four. From preschool through twelfth grade, Givens attended schools at which nearly every one of his teachers was black. And not only that, but many of them had themselves grown up in the South, attending Jim Crow-era schools, whose teachers were part of Woodson’s network—a line that stretches all the way from the early decades of Emancipation to 2006, when Givens crossed the stage with his high-school diploma. He remembers his preschool teacher, Miss Butterfield, who had worked alongside her sharecropping family in Mississippi and taught Givens and his classmates, as three- and four-year-olds, to memorize excerpts from King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. In third grade, Ms. Todman, from North Carolina, built lessons around Nat Turner’s rebellion and Eloise Greenfield’s poem about Harriet Tubman (“Didn’t come in this world to be no slave / And wasn’t going to stay one either”). Every morning at Givens’s black parochial elementary school, students would sing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” the black national anthem. “I know the words by heart,” he says. “It was just this embedded set of norms and rituals in the academic culture.”

In high school, Givens attended King/Drew, a high-achieving magnet school in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, a stone’s throw from the public-housing projects. In 2004, when African American novelist Edward P. Jones won the Pulitzer Prize for The Known World, the school organized a reading marathon in the auditorium. Students could leave class to drop by and listen or read aloud from the book; the event continued late into the evening.

One prominent figure at King/Drew was the strict-but-loving English teacher Ms. Hutchinson, who gave Givens the prescient nickname “Professor,” and who as a child was inspired by her own teachers at the Frederick Douglass School in Hot Springs, Arkansas. She hosted annual reading marathons at her house during winter break, where current and former students would gather and read to each other from the canon of black literature. “Lesson-planning with my colleagues, deciding which texts we would use to meet education standards, it was always with the awareness and intentionality that we were educating black students,” says Givens’s tenth-grade English teacher Latosha Guy, who as a child attended school in Huntsville, Alabama, where her mother was a teacher. She sees parallels between the teachers in Fugitive Pedagogy and her own relationship with students at King/Drew, “in the sense of this tradition of black educators not only teaching reading, writing, and arithmetic, but also showing students about navigating racism, and about the beauty of African American history and culture.…At King/Drew we would teach students lessons—not always overtly, sometimes just in our dispositions and demands—about code-switching, always being proud of who you are and where you come from, but knowing that you have to exist in another world.”

Arriving at Berkeley as a freshman, Givens discovered that, unlike him, few of his African American classmates had black teachers growing up. Later, during his first year of graduate school, he read Their Highest Potential, historian Vanessa Siddle Walker’s [Ed.D. ‘88] account of a strong, successful black school that existed in segregated Caswell County, North Carolina. For Givens, a light went on. “I had never resonated with the stories of black underachievement, the experiences of black suffering in schools that are quite common for many students,” he says. “What resonated with me were the stories in Vanessa Siddle Walker’s book.” Which led him to the historical questions he’s been working to answer ever since, “about this world of black teachers and black education prior to Brown v. Board of Education, which was more expansive than this story of separate and unequal that we tell and retell.” And his next book, due out in the next year or so, approaches those questions again, from a slightly shifted perspective: that of the students. School Clothes: A Collective Memoir of Black Student Witness returns to the autobiographies of civil-rights leaders and the first-person accounts of less well-known figures like Jerry Moore, the D.C. reverend who reminisced about sitting in Tessie McGee’s classroom, to piece together a historical record built on black student voices. “I’m interested in what it has meant to be a black student in the context of American schools,” Givens says, “and what that history offers to black students in the contemporary moment.” His own educational experience frames the book, and Givens also interviewed some of his former teachers. “Reading across these lived histories in various forms from various times,” he says, “this is an important extension of the historical record that forces us to confront the distinct experiences of black students. And we’ve yet to do that in a meaningful way.”

The familiar stories of “aggressive neglect and unequal resources” in majority-black schools “are absolutely true,” Givens adds. “But there’s a lot more to the narrative”—a more complicated history of “black spiritual strivings” in education, of agency and resistance. He knows that story exists, because he lived it.