Say it once and it sounds like a tongue-twister. Say it again and it sounds like an oxymoron: “Soviet state-sponsored anti-bureaucracy propaganda posters.” It’s still a tongue-twister, but on closer inspection, it’s less of an oxymoron than you might think.

After Stalin’s death in 1953, the USSR took stock of itself. Soviet bureaucracy and its many abuses had ballooned. Fearing repercussions from the state, farmers falsely reported record-high yields during food shortages; factories claimed peak operational efficiency with underwhelming output; and despite the state’s growing payroll, none of the paper-pushing moved any faster. Looking to de-Stalinize and reform, the USSR turned to a Leningrad-based group of poets and cartoonists known as the Fighting Pencil.

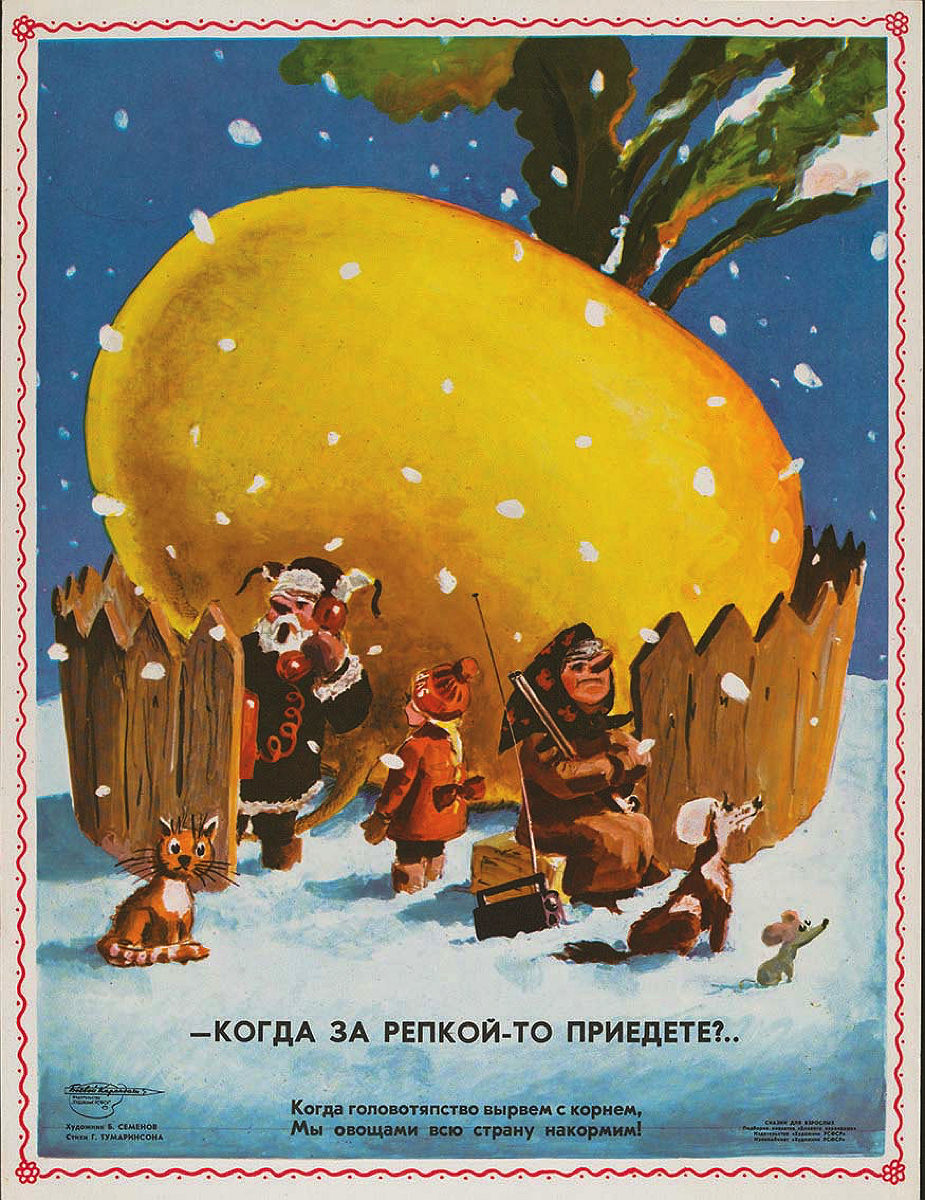

—When are you going to take the turnip out?

We can feed the whole country with vegetables.

From the 1950s until the fall of the Berlin Wall, these artists produced hundreds of government-sponsored, colorful, funny, and downright scathing posters railing against the inefficiencies and abuses taking place under the Soviet state. These posters, about 80 of which are now held by the Davis Center Collection at H.C. Fung Library, hung in bus stations, offices, and any public place a crooked bureaucrat might see them.

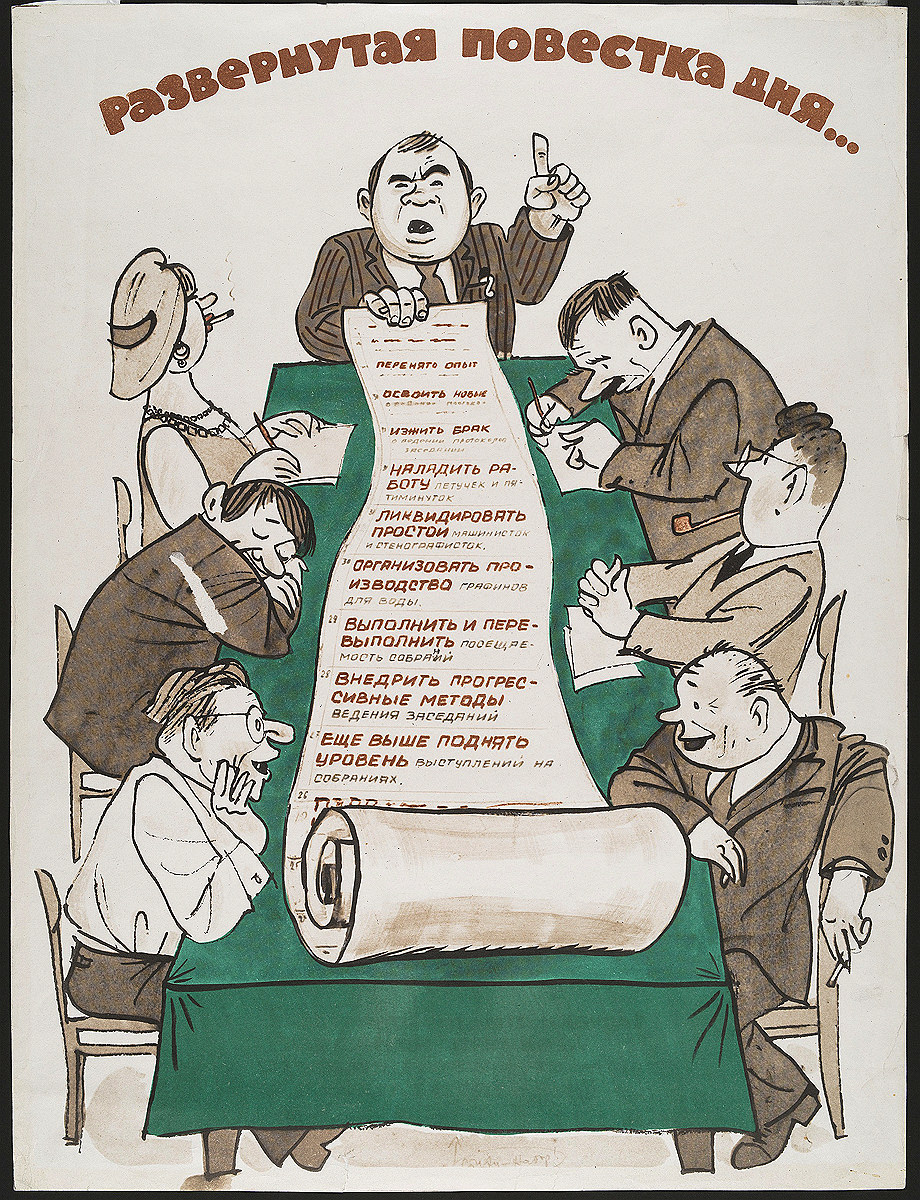

Detailed Agenda

Adopt best practices

Utilize new methods

Eliminate waste from the minutes of meetings

Improve the workings of meetings and briefings

Liquidate simple typists and stenographers

Organize the production of water-pitchers

Fulfill and over-fulfill the attendance of meetings

Introduce progressive methods of conducting meetings

Raise higher the level of speeches at meetings.

“They’re like New Yorker cartoons on steroids,” says librarian for the Davis Center Collection Svetlana Rukhelman. Combining cartoons reminiscent of Russian folk-art woodcuts (lubok) with a witty poem and sometimes a newspaper article excerpt of an actual bureaucratic abuse, the posters denounced everything from bribe-accepting bosses and lollygagging employees to government conferences held in luxe tropical locales at public expense. Some posters transposed Russian folklore into the bleakly bureaucratic USSR, like “The Gigantic Turnip,” a children’s tale about a family who struggle to pull a massive turnip out of the ground until a tiny field mouse helps them. In the Fighting Pencil version, the family and the mouse spend a winter waiting for the state-sponsored turnip-picking service to arrive. (It never does.)

Zonal Conference for Developing the Forest Tundra

—And the doors?! You haven't made the doors!..

The new warehouse is solid and good,

The absence of doors doesn't even show.

The “innovative” practice used here

Is quite common, as all of us know.

As far as government-sponsored propaganda goes, these posters were benign, but they were still propaganda. The Fighting Pencil could lampoon the fruits of the Soviet system, but not the system itself. Low-level bureaucrats were a safe target, but “never those at the top,” says Rukhelman. Occasionally, the Fighting Pencil directed its snark too close to the Communist Party, and the state would decommission them for years at a time. But even if the Fighting Pencil couldn’t express the whole truth, citizens could see it for themselves. Eventually they got tired of waiting for fully stocked grocery shelves, honest bureaucrats, and the proverbial state-sponsored turnip-picking service to arrive.