Harvard’s annual financial report for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2020, published today, shows the initial, adverse impact of the coronavirus pandemic as:

- revenue decreased by 3 percent, to $5.4 billion; and

- the University recorded a $10-million operating deficit.

The financial results require careful interpretation, because they reflect only the first few months of the pandemic, and were in turn influenced by a few one-time items (see discussion below). But for perspective, note that the decreased revenue and deficit contrast sharply with the robust results of just 12 months ago, when Harvard reported 5.7 percent revenue growth during fiscal 2019 and a $298-million surplus (restated this year to a $308-million surplus): the sixth consecutive year in the black.

Given current operations—with enrollment in many schools’ degree programs down, in-person executive and continuing education suspended, and significant costs to ramp up remote instruction (read about the graduate schools’ spring-semester plans, unveiled earlier this week) and for virus testing, contact tracing, and other public-health measures—the University is likely operating at deficit, perhaps a significant one.

In his introductory message in the report (the cover of which appropriately bears images of remote instruction, and of the masked John Harvard statue, socially distanced as ever), President Lawrence S. Bacow acknowledged that the pandemic “has changed our world in profound ways.” He cited such continuing strengths as University scientists’ work on COVID-19 prevention and cures—and that of other faculty members on racial disparities, inequality, global poverty and other significant social challenges: work at the core of Harvard’s scholarly mission. He also cited a $31-million increase in financial aid and scholarships during the year, consistent with the educational mission. That said, he cautioned that “[W]e at Harvard, along with colleagues at other colleges and universities, have tough decisions ahead of us. How we manage declining revenue and rising need for investment in excellence amid new and necessary health protocols will, in part, determine our successors’ ability to endure and thrive.”

Thomas J. Hollister

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/HPAC

In their financial overview, vice president for finance and chief financial officer Thomas J. Hollister and treasurer Paul J. Finnegan wrote that the financial effects from the onset of the pandemic “were significant and sudden.” The $138-million drop in revenue (from canceled executive education, room and board refunds, temporary closing of laboratories conducting sponsored research, and the cessation of events, reunions, parking, and rental income from Harvard-owned properties) reflects essentially the last quarter of the fiscal year. Given that until then, revenue had growing more or less in line with Harvard’s experience in recent years (4 percent to 5 percent annually), they calculated the actual effect was $270 million of “lost revenue”: annualized, a run rate of about a billion dollars, or close to one-fifth of expected revenue.

In light of those large revenue losses, Hollister and Finnegan credited the entire community for implementing immediate reductions in discretionary spending, accompanied by hiring and compensation freezes, elimination of bonuses and overtime work, voluntary salary cuts taken by senior leaders, and reduced capital spending. (The report narrative cites a $155-million reduction in discretionary spending.) And they applauded the community’s swift pivot to online learning, and subsequent efforts to reopen laboratories, adapt campus to accommodate a reduced population safely, and implement robust virus testing and contact-tracing protocols.

“Unfortunately,” they continued, “The hardest part likely lies ahead.” For at least the current fiscal year, “Declining revenues and increasing costs is not a sustainable equation, but it is our near-term reality.” Given huge uncertainties about public-health conditions and the spring semester, they are emphasizing liquidity (maintaining sufficient operating cash); reducing spending in line with declining revenues; and being “on the lookout for investment opportunities that will strengthen the mission for the future.”

The financial report also contains details about Harvard Management Company’s (HMC) endowment investments (see below).

Highlights of the University’s fiscal year:

- Revenue declined $138 million to about $5.4 billion, following growth of 5.7 percent in fiscal 2019, 4.3 percent in fiscal 2018, and 4.6 percent in fiscal 2017. Although distributions from the endowment—the University’s largest source of revenue (see discussion below)—increased about $90 million, to $2 billion, other sources of funds were reduced, or choked off, by the pandemic.

- Expenses rose by $180 million, or 3 percent, despite the emergency economies toward the end of the year, noted above; but this figure contains one-time items that increased the reported expenses significantly.

- The result was an operating deficit of $10 million.

Even with those one-time items accounted for in the past year, fiscal 2021will reflect the full-year effects of the pandemic on all core University programs. Revenue last declined in fiscal year 2010, in the aftermath of the Great Recession and the sharp decline in the value of the endowment and other Harvard investments—but growth resumed the following year. That is highly unlikely this time, reflecting the very different nature of this crisis.

The Financial Year in Context

Revenue. Total student revenue decreased 11 percent ($130 million), from $1.2 billion to less than $1.1 billion. This highly unusual result requires unpacking. Undergraduate and graduate programs, in aggregate, had planned some modest decreases in net revenue (after financial aid), according to the report. But revenue from executive and continuing education—a half-billion-dollar business that grew 12 percent in fiscal 2019 and was well on its way to exceeding net tuition from all degree programs this year—was essentially shut down by the pandemic: it instead declined by $90 million (down 18 percent), to $410 million. Board and lodging revenue declined, too—down 16 percent ($32 million), to $164 million—reflecting refunds issued after campus was emptied in March.

Surprisingly, sponsored support for research, largely recorded when spent, held up much better than expected, declining only about 2 percent ($20 million), to $918 million. Although research in laboratories was curtailed during the spring, Harvard scientists and scholars turned out to be able to conduct much of their work (not all of which requires wet-lab benches) remotely, and then to resume activity with modified facilities and procedures, and personal protective equipment, more quickly than anticipated. Importantly, that activity enabled the University to receive the “indirect” payments associated with research, which cover costs associated with buildings and facilities; such support was nearly level for the year. And some incremental research projects focused on the coronavirus were funded during the year.

A second surprise came in the form of sustained philanthropic support. In fact, donors responded to the obvious strains caused by the pandemic (getting students safely off campus, providing for their learning from home, supporting remote teaching)—and presumably to deans’ and fundraisers’ pleas—and increased current-use giving to $478 million: $5 million above the prior-year total. As noted, the endowment distribution (in effect, the result of prior philanthropy, plus the substantial earnings on investments accrued through the decades) rose nearly 5 percent, to $2 billion, reflecting the University’s 2.5 percent increase in distributions per endowment unit, plus schools’ distribution from new endowment units owned (reflecting proceeds from The Harvard Campaign and other gifts).

The revenue in context. The changes effected by the last quarter of fiscal 2020 were significant enough to alter the composition of the University’s financial profile overall. As shares of aggregate revenue:

- student income decreased from 22 percent in fiscal 2019 to 17 percent;

- sponsored research contributed 17 percent in each year;

- current-use giving rose from 8 percent to 9 percent;

- the endowment distribution rose from 35 percent to 37 percent; and

- all other sources rose from 18 percent to 20 percent.

Those shifts are large for a single year for a traditionally stable institution like Harvard, and consequential for the future.

Philanthropic support may not be sustainable. In their letter, Hollister and Finnegan cautioned that “many of the donations in the spring were in the form of early collections on past pledges,” so pledge balances decreased—as they ordinarily would after a capital campaign, unless replenished by new gifts. “In the current environment,” they warned, given the economy, “we should anticipate less philanthropy in the coming year.” In fact, according to the financial footnotes, pledges receivable for current-use gifts decreased by $120 million (to $624 million), and pledges for gifts to the endowment decreased by nearly as much (to $1.3 billion), after unexpectedly robust growth during fiscal 2019.

And there is a warning as well in the swelling importance of the endowment. Although exact guidance for fiscal 2022 is not known, following level-funding of the distribution this year, deans have been cautioned that investment returns are not expected to be robust, so that they ought to think about their funds from that source (not only the largest source of revenue University wide, but the majority of funding for the Radcliffe Institute and the divinity and arts and sciences faculties) trending “sideways.”

Absent a capital campaign, schools are less likely to secure major endowment gifts, lessening that significant source of growth in their investment assets after several years of meaningful gains (note the declining pledge balance). And as their operating budgets are squeezed, they are less likely to generate surpluses, which some schools have been able to invest in recent years, further augmenting their base of endowment assets, and thus the income they receive in future distributions. So the levering-up of endowment assets from The Harvard Campaign and the past six years of large surpluses—leading to a boost in revenue from distributions—is now reversing, just as many schools, and the University as a whole, are more endowment-dependent.

Expenses. The reported increase in expenses reflects offsetting factors. Given University operations up to the point of the pandemic, expenses presumably were growing at a 3 percent to 4 percent rate. Then, the spigot was turned off. For the year, for example, travel expense declined $33 million, to $71 million. In addition to the employment and compensation actions described above, term appointments were not renewed when they came to an end, and other economies were effected.

Compensation expense (salaries, wages, and benefits) increased $158 million (6 percent), to $2.7 billion, in part reflecting normal growth in employment and salaries and wages earlier in the year, offset later in the year by the hiring freeze, term appointments running out, and—during restrictions on discretionary medical care—reduced doctor visits and health-benefit expenses. There was also a modest increase in cost from the annual interest-rate adjustment in pension-benefit calculations, versus a modest decrease in the prior year.

But the major swing factor was a $71-million accrual for the costs of the Voluntary Early Retirement Incentive Program offered to nearly 1,600 senior staff members in June. Nearly 700 accepted the offer—extending to vice-presidential-level staff members. The accrual covers the estimated expense of the salary incentive to retire (a year of salary) and, perhaps to a lesser extent, related benefit costs. (The program should, of course, result in operating economies in the future as those who elected to retire do so, and positions are left open, restructured, or ultimately refilled.)

Noncompensation costs rose as well, driven by the miscellaneous “other expenses” category, which rose from $558 million to $631 million. The driving item there was “fixed asset impairments”—a category that customarily includes accounting adjustments when buildings are renovated, costs for environmental remediation, and so on. This year, however, the impairment line is $182 million, up from $41 million. The large expense is understood to be associated with the carrying value of the huge science and engineering center on Western Avenue, across from Harvard Business School, to which much of the engineering and applied sciences faculty will begin to relocate starting next month. The huge subbasement on which the complex sits was originally designed to support a much larger above-grade facility than the one that now exists

(it was redesigned after construction was paused following the Great Recession), and the uses have changed as well, so the carrying value has to be adjusted, in accord with accounting practices, as the complex nears commissioning.

Balance sheet and capital items. Debt outstanding increased from $5.2 billion at the end of fiscal 2019 to $5.7 billion at the end of fiscal 2020, as the University took advantage of low interest rates to issue $500 million of taxable debt, bearing a 2.5 percent interest rate. (It also refinanced commercial paper, locking in a 2.6 percent interest rate on $350 million of debt.)

During the spring, construction was halted to protect workers’ health at the height of the Massachusetts pandemic. In addition, the University moved as quickly as possible to reduce construction spending, so it could apply those dollars to operating needs. As a result, spending on capital projects and acquisitions plummeted to $627 million from a near-record $903 million in fiscal 2019. Major projects are being completed (the Allston science complex, the Divinity School’s Swartz Hall renovation, the Law School’s Lewis Hall expansion and renovation, current phases of Adams House renewal, the Houghton Library renovation), but successor projects are being reconsidered. Adams House renewal, for example, will be extended into mid decade.

Consistent with the University’s determination to remain liquid, cash, equivalents, and short-term investments held outside the General Investment Account were $1.6 billion at the end of the fiscal year, up from $1.0 billion at the end of fiscal 2019.

In prospect. After the last half-year, no one professes certainty about what the rest of fiscal 2021 will bring. Online executive and continuing education programs continue, but in-person programs, on campus and elsewhere, are essentially on hold so long as the pandemic continues and travel is curtailed; that represents hundreds of millions of dollars of revenue at risk, for Harvard Business School (HBS, which has four buildings on campus devoted to executive programs), the Faculty of Arts and Sciences’ Division of Continuing Education, and executive-education programs that account for significant sums at the Graduate School of Education, the Harvard Kennedy School, and elsewhere.

Atop those challenges, degree-program enrollment has declined in some schools, too. HBS has about 260 fewer M.B.A. students enrolled than its typical two-year cohort of 1,800. The College enrolled 5,382, compared to the usual census of about 6,600—representing a significant loss of tuition income (even after financial aid); and with less than one-quarter of those enrolled undergraduates in residence, but distributed across the Yard dorms and Houses to ensure safe distancing, it is collecting far less in room and board fees, but maintaining employment of service workers. Schools with large international enrollments, like the Kennedy School, may also be pressed. And the costs of high-frequency virus testing (three times weekly for undergraduates in residence; once or twice weekly for those faculty and staff members regularly on campus) and other safety measures are estimated at tens of millions of dollars annually.

So the conditions in place today present significant challenges. In a conversation earlier this week, President Bacow said that in light of the University’s prior preparations for leaner times, “No school is in distress—but all are feeling financial pressure.”

The Endowment: The Ship Turns

Harvard Management Company CEO N.P. Narvekar’s annual letter on the endowment, which amplifies the bare-bones September announcement that it earned 7.3 percent on investments during fiscal 2020, continues the narrative of transformation that began with his appointment in December 2016. Of note, the changes in the composition of the investment portfolio continue apace, and performance was good this year (MIT had an 8.3 percent return, and Yale 6.8 percent; Princeton and Stanford have not reported yet). [Updated October 23, 2020, 2:15 p.m.: Stanford reported a 5.6 percent investment return for fiscal 2020; the value of its endowment rose to $28.9 billion. Updated October 26, 2020, 12:15 P.M.: Princeton also reported a 5.6 percent investment return for fiscal 2020, and its endowment was valued at $26.6 billion. Thus HMC can claim some bragging rights for the year, among its nearest peers.] And there is potential for more progress to come—not least as the impact of underperforming assets diminishes further.

N.P. Narvekar

Photograph by Stephanie Mitchell/HPAC

Several themes are implicit in Narvekar’s report:

- First, the wholesale restructuring he initiated, and initially described as a five-year project, is largely complete (read about details below), faster than forecast. That frees him and senior colleagues to focus almost entirely on investment performance, as they push for superior results within the University’s requirements, over the course of economic and financial cycles.

- Second, HMC’s performance has been relatively good, perhaps even unexpectedly so, during the restructuring—a bonus result. In discussing the public-equity results (see below), Narvekar noted that relative performance was quite strong—even more in fiscal 2020 than in the prior years.

- Third, that performance has been realized even as HMC has assumed less investment risk than some peer institutions. HMC’s public-equity investments—stock portfolios and substantial hedge-fund assets (all managed externally)—are more liquid and less risky than the portfolios of peer institutions that have proportionally greater asset allocations to illiquid private-equity investments. In the immediate past, that suggests that HMC’s equity managers have performed exceedingly well: good news, but old news, and not necessarily sustainable. The longer-term portfolio performance, in absolute and relative terms, will likely depend more on asset allocation, and Harvard’s determination about how much extra risk it might take on (by increasing private-equity commitments to venture-capital and other investments).

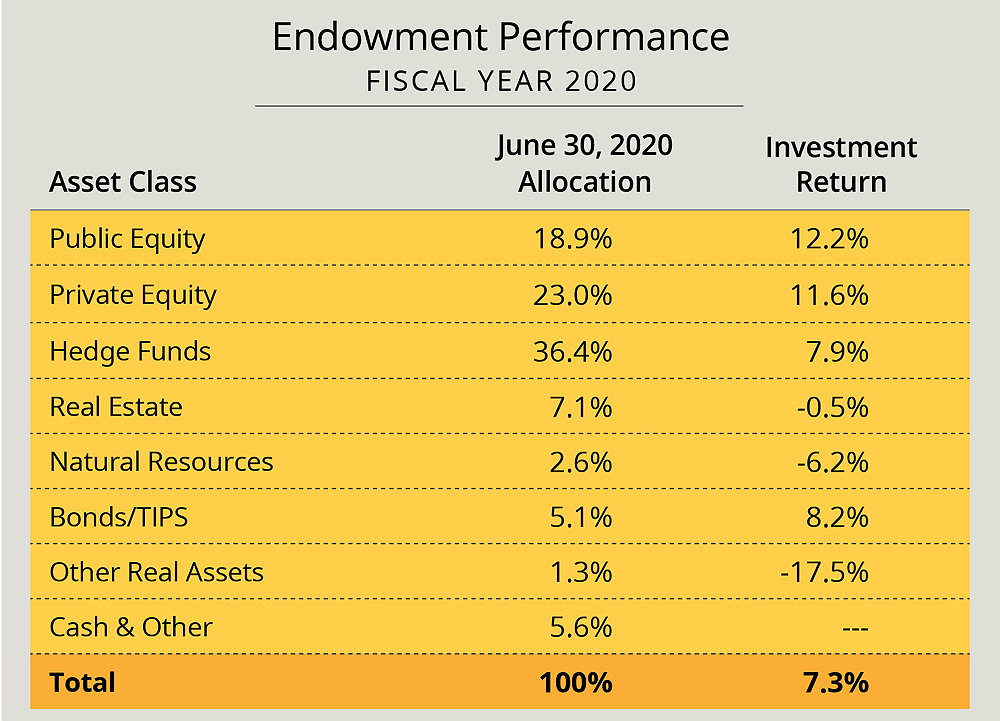

The highlight numbers for the year, disclosed in the letter (part of the annual financial report), are displayed here.

• The year that was. Assessing the year, Narvekar wrote that this was “another year in which asset allocation (or risk level) played a major role in returns. Those who took the highest risks, generally speaking, garnered higher returns”—as witness the strong results in equity assets. Focusing on public equities, he amplified:

In last year’s report, I noted that our annualized benchmark outperformance in the public markets portion of the portfolio (public equities and hedge funds, in aggregate), during the two-year period of FY18 and FY19, was in excess of 2.25% annualized. We considered this to be very good, albeit not excellent. More importantly, it represented a positive step for HMC. It is worth noting again that we do not fixate on benchmarks, but they serve a unique role in this circumstance for a few reasons:

- Investments in public markets are ones on which we can have the most immediate performance impact over the three fiscal years of the HMC transition.

- Public investments represent more than half of the endowment portfolio.

- All relevant private market benchmarks are not yet available.

At the end of FY20, HMC’s three-year public portfolio annualized outperformance now stands at 4.4%, reflecting excellent performance for that period. This represents another positive step forward for HMC and a strong affirmation of our early progress in effecting the turnaround.

He noted that the strong performance of external fund managers in these asset classes helped offset HMC’s lower-than-desired exposure to private-equity investments, particularly the high-risk/high-reward venture-capital sector.

His comments on the year perhaps merit one modification (his “generally speaking” remark). This was also a period when traditionally safe assets—bonds—delivered outsized performance, as shown above, reflecting the worldwide reduction in interest rates in response to the economic calamities spawned by the pandemic.

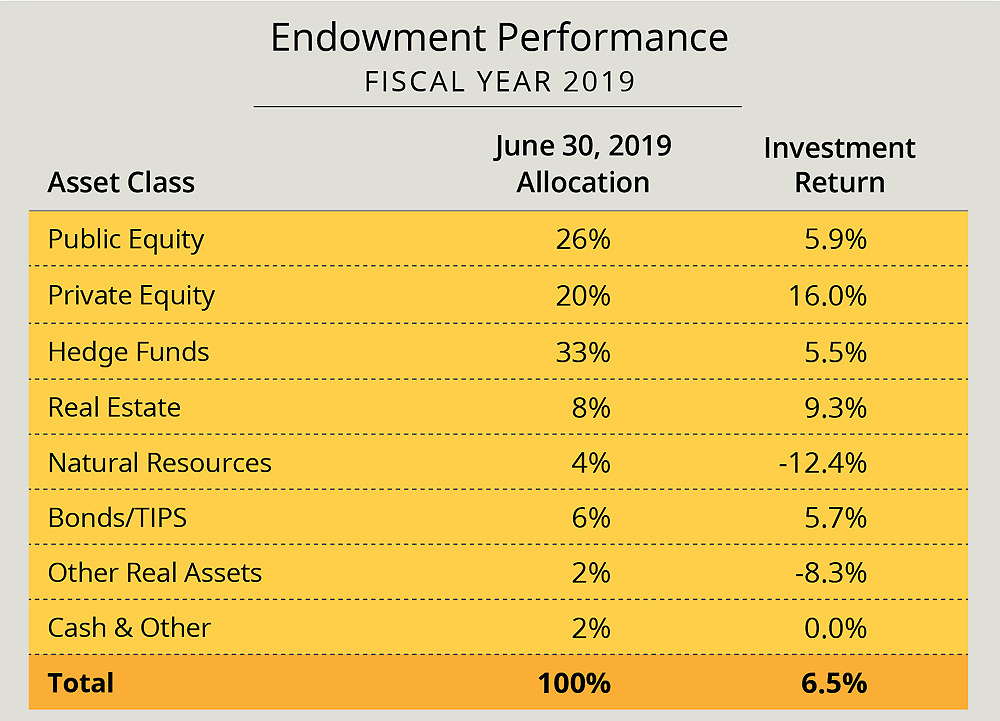

• Cutting the anchors loose. Another way of assessing fiscal 2020 is to examine the diminished influence of underperforming assets. As shown, natural-resources holdings—agricultural and timber land—again produced a loss (-6.2 percent return). So did miscellaneous other private-fund investments, reported as “other real assets” (-17.5 percent return). But those holdings affect HMC’s results less, because they totaled 3.9 percent of assets in the latest year, versus 6 percent in fiscal 2019 (see exhibit).

Of these “illiquid portfolio anchors weighing down…performance,” Narvekar wrote:

These legacy assets do not have a prospect of generating a return commensurate with the risk and illiquidity they entail and, in some cases, may not provide a return at all.…[T]hese assets weighed materially on performance again this past fiscal year. However, the very positive news is that through sales and necessary write-downs we are working our way through these assets and are very pleased that they now represent a considerably smaller percentage of the portfolio—now just in the lower single digits. Our goal is to eventually remove them entirely from the portfolio, as opportunities present themselves, and we believe there is a chance of doing so over the next two fiscal years.

In fiscal 2020, those two classes of assets produced investment losses of perhaps $150 million or so (reducing the approximately $2.7 billion of reported aggregate investment returns by that amount). Subtraction (shedding the remaining unproductive assets) thus will represent addition: redeploying the funds should boost returns In fact, after the fiscal year closed, HMC spun out its natural-resources team into an independent firm, Solum Partners, and sold a half interest in various agricultural assets to a third-party investor, with Solum managing the portfolio. The Solum team will manage “and ultimately liquidate” other HMC natural-resource assets, while pursuing certain investment opportunities HMC may wish to pursue in the future. This is the latest, and last, spin-out of an investment team dedicated to a particular asset class, essentially completing the transformation of HMC into a generalist organization responsible for the portfolio as a whole, which engages external managers to invest the assets.

• Other 2020 factors. Real-estate holdings have been shrinking, too, over time, albeit less dramatically in the recent past: 8 percent of assets in fiscal 2019, when they produced a strong return, versus 7.1 percent in the most recent year, when they yielded a slight loss. (It seems likely that fiscal 2020 results for both natural resources and real estate included some write-downs or other recognitions of losses on legacy assets.) But the Narvekar team’s earlier decision to reduce real-estate commitments, and to spin out that investment team—driven by their view of market cycles, valuations, and the characteristics of such assets versus their risk and reward potential—may prove prescient for another reason. The pandemic-related carnage in the hotel, office, and retail sectors (major components of many real-estate portfolios) may depress values in coming years. Again, redeployment of investments away from this class of assets may be additive in the future.

Finally, HMC boosted its reported cash holdings substantially in fiscal 2020, to 5.6 percent from 2.0 percent the prior year: an increase of about $1.5 billion; in the current environment, earnings on cash holdings are essentially nil. HMC does not aim to maintain a cash reserve within the endowment, so this apparent bulge may be more a short-term accounting item as of the date of the annual financial statements: the timing of distributions to Harvard, and of fund transfers to effect investments.

• The transition in perspective. Although Narvekar’s sweeping moves to remake HMC, its investment strategies, and its operations since late 2016 underlie its performance, perhaps the clearest way for an external observer to see the changes taking place is to compare the mix of assets, above, with those in place during fiscal 2016, just before he arrived that December. The categories do not align exactly, but as of June 30 that year, assets were allocated among:

- public equity (reported as domestic, foreign, and emerging-market stocks), 29 percent;

- private equity, 20 percent;

- “absolute return” (hedge funds), 14 percent;

- real estate, 14.5 percent;

- natural resources, 10 percent; and

- bonds (domestic, foreign, inflation-linked TIPS, and high-yield assets), 12.5 percent.

As of this past June 30, the public-equity and hedge-fund allocations have been augmented by more than 12 percentage points, with a sharp shift away from HMC’s stock portfolios (then internally managed) toward hedge funds. (That bulge in hedge-funding holdings may persist; or it may be a transitional phase if the University decides to redeploy assets toward private equity—a very long-term, painstaking process.) The proportion of assets allocated to real estate has been halved; that allocated to natural resources and other real assets has been cut by nearly two-thirds. Bond holdings have been similarly downsized.

That is a much different profile for the endowment, effected in relatively short order, with a pronounced shift away from fixed-income, real-estate, and natural-resources assets toward public equities (albeit much differently composed and managed).

• Other items of note. Having effected HMC’s transition to a much smaller, generalist investment organization, Narvekar is further simplifying its functions. He announced in his letter that HMC’s Trusts & Gifts group, which works with Harvard’s Planned Giving Program (for estates, trusts, non-cash assets, annuities, and donor-advised funds) to provide processing, administration, and stewardship services, will now outsource many of its functions. The endowment will continue to be an investment option for donors’ remainder trusts. Oversight of the third-party servicer, and of remaining non-investment functions, with be integrated with the University’s development organization over the next year.

Narvekar also referred to three investment-related matters. First, discussions continue between HMC and Harvard to determine the University’s risk tolerance, and therefore the bounds of investing in illiquid assets such as certain kinds of private equity—a matter heading toward the Corporation, the University’s fiduciary governing board, for discussion and a decision. As he put it:

Our goal clearly is to maximize returns at the risk level determined by the University. Close followers of these letters will note that HMC’s returns would have been materially higher in FY18, FY19, and FY20 with a higher risk level—in particular, with a higher venture capital allocation—consistent with that of some of our peers. Simply put, it is a tradeoff between higher returns and more long-term growth in the endowment versus having a less volatile University budget. This remains a critical and complex collaboration with the University, one that is well under way and will guide future portfolio construction.

It also remains a complex issue for the schools, whose reliance on the endowment for their funding differs dramatically, ranging from nearly total (85 percent for the Radcliffe Institute), to very significant (68 percent for the Divinity School and 53 percent for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences), to the merely important (the business and public-health schools, respectively 20 percent and 19 percent).

Second, he noted the University’s recently adopted greenhouse-gas “net-zero” pledge, intended to apply across the endowment by 2050. “This decades-long commitment is in its infancy,” he noted, “but HMC has already begun work developing methodologies to assess our portfolio and measure our progress over the course of this significant endeavor.” Read more in “Addressing Climate Change” and HMC’s statement on “Harvard Endowment Net-Zero Portfolio Commitment.”

Third, addressing diversity and inclusion, he wrote, “[I]t is my strong view that diversity and inclusion efforts begin with our own team. We cannot expect more from our managers than we are willing to ask of ourselves. Currently, 55 percent of HMC’s senior staff members, including myself, are either ethnic and racial minorities or women. All high-performing organizations must draw talent from the broadest possible pool and the diversity of our staff is one way to ensure that we meet that standard.” A letter from Narvekar to members of the U.S. Congress on diversity issues details these issues, and HMC’s roster of external managers, at length.

• A bit of housekeeping. When HMC reported its rate of return in September, a rough estimate was provided suggesting that the endowment grew from $40.9 billion at the end of fiscal 2019 to the $41.9 billion reported as of this past June 30 in this fashion:

- $40.9 billion beginning value as of July 1, 2019,

- plus $3.0 billion (fiscal 2020 investment gains),

- minus $2.0 billion in operation distributions for the University budget (with no estimate made for nonoperating “decapitalization” distributions),

- plus perhaps $100 million in gifts for endowment received,

- equals the endowment’s reported $41.9-billion value as of this past June 30.

With the data from the annual financial report in hand, it is now known that investment gains (which are time-weighted) and income were over-estimated, and in fact totaled about $2.7 billion, and that gifts for endowment were accordingly under-estimated: they were in fact $469 million. Pledge balances, which Harvard counts as part of the endowment, decreased by about $200 million.

• In prospect. For much of the past decade, HMC’s investment performance—at times inconsistent, and seen as lagging peer institutions’—has been a matter of concern, even as the University’s revenues have grown robustly. Now, the situation has very much reversed: important sources of University revenue growth, such as executive and continuing education, are severely challenged, but HMC has been overhauled and appears to be making steady progress toward more consistent, competitive results. As noted, Harvard and HMC still have to agree on what level of risk, and therefore what kind of portfolio, is best suited to the University’s needs and aims. But that conversation can seemingly proceed more confidently, given the foundation that has been built by the new endowment-investment organization. Given Harvard’s immense pandemic-related financial challenges, the endowment’s role in anchoring the whole enterprise looms larger than ever, if for unexpected reasons. From here, the HMC staff’s principal priorities focus on implementation: executing their strategies and disciplines rigorously and well.

The University’s operations, and the accompanying financial results, of course do not exist in a vacuum. As Hollister and Finnegan wrote in their overview:

Stepping back from Harvard, we have cautioned in these letters in recent years that higher education in the United States is facing increasing pressures across all its traditional sources of revenue. Unfortunately, the pandemic and the economic contraction [have] exacerbated these issues, and we expect significant difficulty for the sector, with existential issues for some institutions. This looms as one of the many challenges facing our nation due to the pandemic and its consequences. While higher education as we know it will be changed, we hope that it will continue its vital role as the engine of opportunity for students, as well as an ongoing source of new discoveries of knowledge, ideas, and future leaders for a better tomorrow.

Putting that work into the local context, they turned to the academic mission that is continuing despite the very severe challenges immediately ahead:

In the midst of the current difficulties, we are heartened to watch with appreciation as our faculty, staff, students, and alumni actively contribute to the country and the world in providing epidemiological counsel, leading research on COVID-19 cures, taking legal action on behalf of foreign students, breaking pedagogical new ground in remote and hybrid classrooms, contributing resources and talent to our local communities, and finally, publishing articles, papers and research in every field on the effects of the pandemic, and the possible best paths forward.

Read Harvard’s annual financial report (with Narvekar’s HMC letter) here. A Harvard Gazette article on University finances appears here.