Tomiko Brown-Nagin is a legal historian of what she calls “one of the most celebrated social movements of all time—the black freedom struggle.” Two photographs sit on a bookcase behind her desk at Greenleaf House, the residence of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute’s dean—her role since 2018. One shows her with Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the other with Congressman John R. Lewis, LL.D. ’12. They are proxies for contrasting ways she thinks about the American civil-rights movement.

Sotomayor, the first woman of color on the Supreme Court, connects to work Brown-Nagin has done about the movement from the top down, shaped by federal courts, as in her new book on Federal District Judge Constance Baker Motley, called Civil Rights Queen. Lewis, on the other hand, connects to her 2011 book Courage to Dissent about the movement from the bottom up. He was among the early Freedom Riders who challenged Jim Crow laws and headed the bloody march in Alabama from Selma to Montgomery, which led to passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

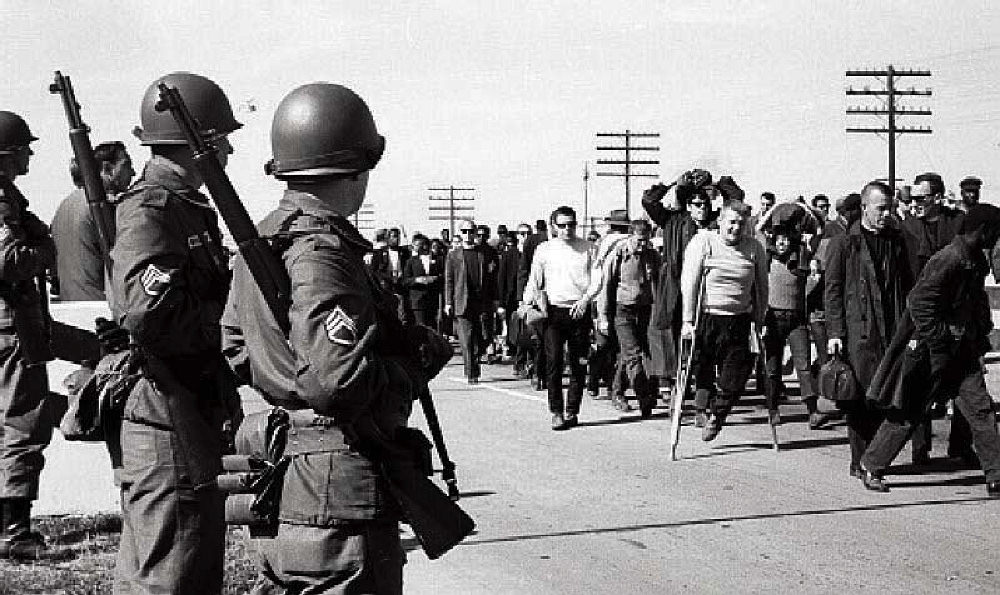

National Guard protection for the marchers

Steve Schapiro/Corbis via Getty Images

The photos were visible recently as Brown-Nagin took part in a Radcliffe online event as chair of the initiative President Lawrence S. Bacow created on Harvard and the legacy of slavery. The effort is necessary, she said, “to understand and address the enduring legacy of slavery within our university.” The discussion touched on delicate issues, which the report on legacies of slavery, expected this winter, is likely to address: bequests of land, buildings, and money connected with slavery, as well as members of the Harvard community who were embroiled in the system of slavery. “As I’ve said many times,” she went on, “we can’t dismantle what we don’t understand, and we can’t understand contemporary inequity and injustice unless we reckon honestly with our history.”

The initiative is based at the Institute because it is an interdisciplinary center for advanced study. The project’s working group, while about one-third historians, ranges across other University fields, from business, education, law, and medicine, through urban design, sociology, and religion. It fits fresh ways she is shaping the Institute for greater real-world impact, by uniting scholarship across academic disciplines and the creative arts with work in professional fields. Brown-Nagin’s interdisciplinary scholarship—a faculty member since 2012, she is Paul professor of constitutional law and professor of history—made her a strong choice to chair the initiative, as did her eminence as a public intellectual.

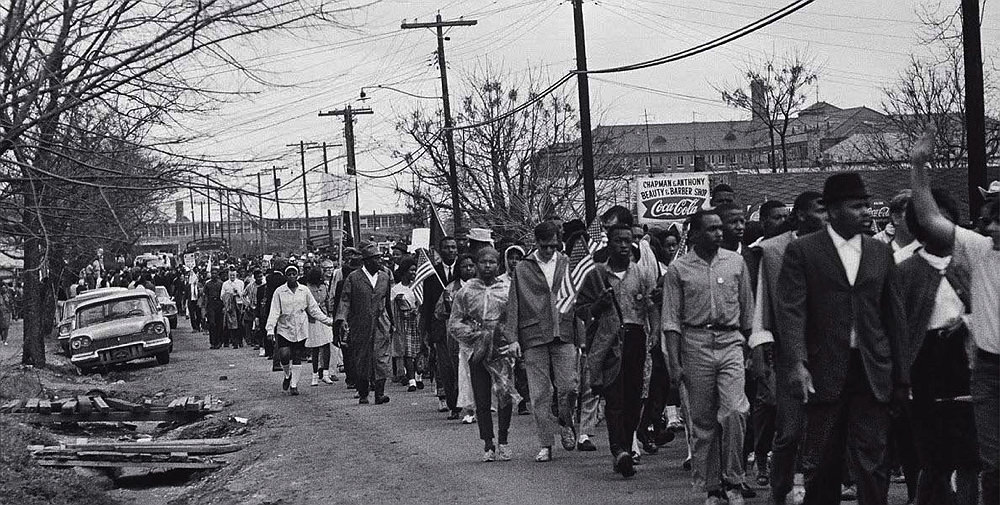

Tear-gassed marcher cradles injured Amelia Boynton Robinson

At the capitol grounds (March 29, 1965)

Brown-Nagin embodies the achievement that the civil-rights movement sought for blacks, women, and other outsiders: the same opportunities as the nation’s most privileged. She is an outsider who became an insider. She bridges often unbridgeable groups of American society. She has the earned confidence of a person wielding considerable power—and the steely purpose of someone who knows what it was like not to have much power at all.

In public events, Brown-Nagin is sometimes overly formal, radiating coolness, as if holding the world at arm’s length. She is a private person. In her bearing and writing, she marshals authority with care and precision, in a voice of tactful consideration. One-on-one, she is wry and attentive. She is a generous and prized mentor. Jelani Hayes, getting a Harvard Ph.D. in history and a Yale J.D. in law, whom Brown-Nagin is mentoring, said, “The thing that she wants to instill is that I approach my work and my career with a high level of confidence and comfort in these spaces.”

Brown-Nagin is especially interested in historical divisions—by class, gender, and race.

Tomiko means “rich woman” in Japanese: she was named for a multiracial great aunt. From a black working-class family, she expresses pride in her roots and gratitude for the nurturing she got from her family and community. “It’s sort of my super-power,” she said. Her family’s perspective is integral to her understanding of history. She is especially interested in historical divisions—by class and gender as well as race.

It takes close attention to realize how contrary are some of her views. Her two books, each a 10-year project, contain notable examples. In the first, she explains why, in Atlanta, Georgia, during the generation after World War II, influential blacks who supported the civil-rights movement had good reasons to “compromise with segregationists.” In the second, she recounts how a “queen” of the movement deserved even greater prominence—why, had she gotten credit she deserved for her work as a groundbreaking lawyer and pioneering judge, she might be widely acclaimed as one of the movement’s heroes.

For the head of a multi-faceted Institute whose work involves a lot of collaboration, the books are individual achievements: they demonstrate Brown-Nagin’s power of intellect and independence of mind, devotion to fairness, and passion for improving access to opportunity. Those qualities provide the foundation of her leadership.

Law as a Field in the Humanities

“My story is one of ascent,” Brown-Nagin said, made possible by her family and by history. The historical aspect was the civil-rights movement, culminating in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the federal lawsuits that eventually enforced Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 decision outlawing segregation in public schools. The family aspect included her parents’ efforts to ensure that she reached whatever heights she could, based on her abilities, without being handicapped by the color of her skin.

Now 51, she was born in 1970 and grew up in Greenwood, South Carolina, a small city 200 miles from the Atlantic coast. South Carolina’s response to the Brown decision was to defy it. The state had funded an “equalization” program, supposedly to make schools for black students equal in quality while keeping them separate from white students—what Brown expressly outlawed: it held that separate-but-equal schools by their nature violate the Constitution’s guarantee of equality. A federal trial judge ordered South Carolina to desegregate in 1963, but the state didn’t accept that order until 1970 and, even then, continued to circumvent its purpose throughout Brown-Nagin’s time in school there.

Her parents, Lillie C. Brown and Willie J. Brown, went to segregated high schools in the 1960s and hadn’t gone to college. “One of the difficulties that first-generation college students sometimes face is lack of family support,” she told me. Through fear of the unknown, families without a tradition of going to college worry that their children won’t be able to find employment if they get a liberal-arts education rather than learning a trade like welding or skill like bookkeeping. The Browns saw beyond that concern. “My parents had not been able to achieve their potential because of discrimination,” she explained: “They promoted my education as a pathway to social mobility for me.”

Tomiko Brown-Nagin

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Brown-Nagin always did well in school and was a pioneer in desegregation. Greenwood students went to public schools run by the county. In the 1970s and ’80s, the average population was about two-thirds white and one-third black. The racial make-up of the schools skewed somewhat higher black, but she was usually the only black student in honors and AP classes. She got a lot of encouragement from teachers, as early as first grade, she said, yet “often in the context of being told explicitly that I was exceptional, that most African-Americans were not like me. And I knew that just could not be the case, because I spent time at school and church and in the neighborhood with other African-American kids who were very talented: they were smart.” The schools’ regular tracks were “overwhelmingly populated” by those kids. The gap between opportunity for white students and for almost all black students was extreme.

Greenwood High School’s graduating class voted Brown-Nagin most likely to succeed. She spent time thinking about what she should do with her talents. In the World Book Encyclopedia, she read the entry about Thurgood Marshall, the great civil-rights lawyer and Supreme Court justice. In the five cases known as Brown v. Board of Education, Marshall filed the case in South Carolina; when he argued at the Court against segregated schools, it was on behalf of South Carolinians. In high school, Brown-Nagin decided that she wanted to go to graduate school to study the history of civil rights—and to law school to become a civil-rights lawyer, to help fulfill the promise of Brown.

She got brochures from many colleges inviting her to apply. Schools like Duke and Harvard fascinated her, but, to her, the cost put those schools out of reach, and her mother was eager for Brown-Nagin to go to college close to home. When Furman University, the respected institution about 50 miles to the north, in Greenville, South Carolina, offered her a full scholarship, she went because of its strong liberal-arts program. It served her well, though the student body was heavily white (2 percent of students were black). She made friends, went to parties and ball games, and considered putting aside her previous plan to pursue a career as a singer instead (a first soprano, she sang in choirs and choral groups).

Brown-Nagin found mentors who urged her to keep to her original path. An English professor, Judith T. Bainbridge, encouraged her to apply for a Truman Scholarship, the national honor that provides for graduate education to about 60 American college juniors who “demonstrate outstanding potential for and who plan to pursue a career in public service.” Brown-Nagin said that she planned to apply to Harvard Law School. At her interview, the then-president of Atlanta’s Spelman College, Johnnetta B. Cole, asked what she would do if she didn’t get into Harvard Law. She got a laugh out of the selection committee by challenging the question’s premise: she said she would go to Yale. They gave her the scholarship.

She graduated Phi Beta Kappa and summa cum laude, winning awards for the top senior thesis and top student in history and for the outstanding senior—in scholarship, character, and participation in college activities. (Her thesis, “‘Moved by Law and Not by Spirit’: Public School Desegregation in Greenville, South Carolina,” argued that whites did little to desegregate voluntarily.) When she got into programs for a Ph.D. at Duke in history and a J.D. at Yale in law, she decided she would pursue both until she figured out which path was better for her. (She got into Harvard Law School too, but went to Yale because many advised it was a better fit for students interested in an academic career.) While she was in law school, her mother earned a bachelor’s degree in education and a master’s degree in educational administration, and became a public elementary school teacher for 20 years. For Brown-Nagin, her mother provided a model of life-long learning and seeking new opportunities.

For 11 years, her life was a blur—from the time she began her first year at Yale Law at age 22, until she began her career as a professor of law and a professor of history at Washington University, in St. Louis, at 33. Brown-Nagin got her academic training and did a range of sought-after apprenticeships. She was an intern at the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department, at the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, and at the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund; a law clerk for Judge Robert L. Carter, LL.D. ’04, a federal trial judge in the Southern District of New York who had argued in the Brown case on behalf of the Kansas petitioners, and then for Judge Jane R. Roth, LL.B. ’65, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit, in Delaware; and, for two years, represented banks and tech companies as an associate in the litigation department of Paul, Weiss, the top-tier corporate law firm in New York City. She finished her dissertation—and got her Ph.D.—while at the firm.

Theodore V. Wells Jr., J.D., M.B.A. ’76, a Fellow of the Harvard Corporation, and a partner at the firm, recruited her. “She was beloved by the Paul, Weiss litigation department,” he said: “I assumed there was a high likelihood that she was going to become an academic, but if she had chosen to stay, I believe she would have become a partner and a great litigator. She is a super-star: brilliant, insightful, hardworking—the full package.”

In 1998, she had married Daniel Nagin, whom she met when both were summer interns at the Lawyers Committee. He is a clinical professor of law at Harvard Law School and faculty director of its WilmerHale Legal Services Center & Veterans Legal Clinic in Jamaica Plain. They have two sons, one in college, the other in high school.

Her experience at Yale—“going there is like attending one long seminar,” she said, with law considered a field of the humanities and social sciences as well as a tool of problem-solving—had convinced her that she didn’t have to choose: history and law were compatible fields. At Yale, she continued to zero in on civil rights and education, writing papers about the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s campaign for school desegregation and about the role of state, as opposed to federal, courts in that process. As a research assistant to Professor Reva Siegel, Brown-Nagin worked on a major law-review article of Siegel’s about “preservation through transformation”—how the legal system preserved white privilege while adjusting rules and rhetoric. The article was Brown-Nagin’s introduction to legal history with attention to the roles of race and racism in America.

At Duke, the historian William H. Chafe ’62 helped her realize the importance of place and of people at the grassroots in shaping events through the academic discipline of social history. The field focuses on the interactions of different groups in society and the social structures affecting them, countering the emphasis on elites in fields of history (diplomatic, intellectual, and political) that often neglected everyone else.

Her dissertation was a combination of legal and social history, called “Class actions: the impact of black and middle class conservatism on civil rights lawyering in a New South political economy, Atlanta, 1946-1979.” As a professor of law and history in St. Louis for three years and in Charlottesville for six at the University of Virginia, where she moved to a tenured post, Brown-Nagin expanded her dissertation into the book Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement. It won a 2012 Bancroft Prize for works on American history, among the field’s most prestigious awards. Other stars in the field called it “a magnificent achievement,” “a “magisterial account,” and “an absolutely compelling study.” The book moved her to the first rank of American historians.

Ending Jim Crow from the Grassroots

Courage to Dissent, about Atlanta during the long civil-rights movement, is a big book—in length, scope, and ambition. It is about the elite black lawyers of the NAACP and its Legal Defense and Education Fund, or LDF, middle-class lawyers and others in Atlanta, political leaders ranging from elected officials to student protesters, and people living in poor black ghettos. It’s about the era from 1946, after the end of World War II, to 1979, just before the start of unequivocal retrenchment in civil rights. Atlanta, Brown-Nagin wrote, was in the mid-twentieth century a “thriving metropolis of black education,” with about one-third of the city’s 300,000 people black and two-thirds white in 1940 and, in 1970, with the population grown to 500,000, about half black and half white.

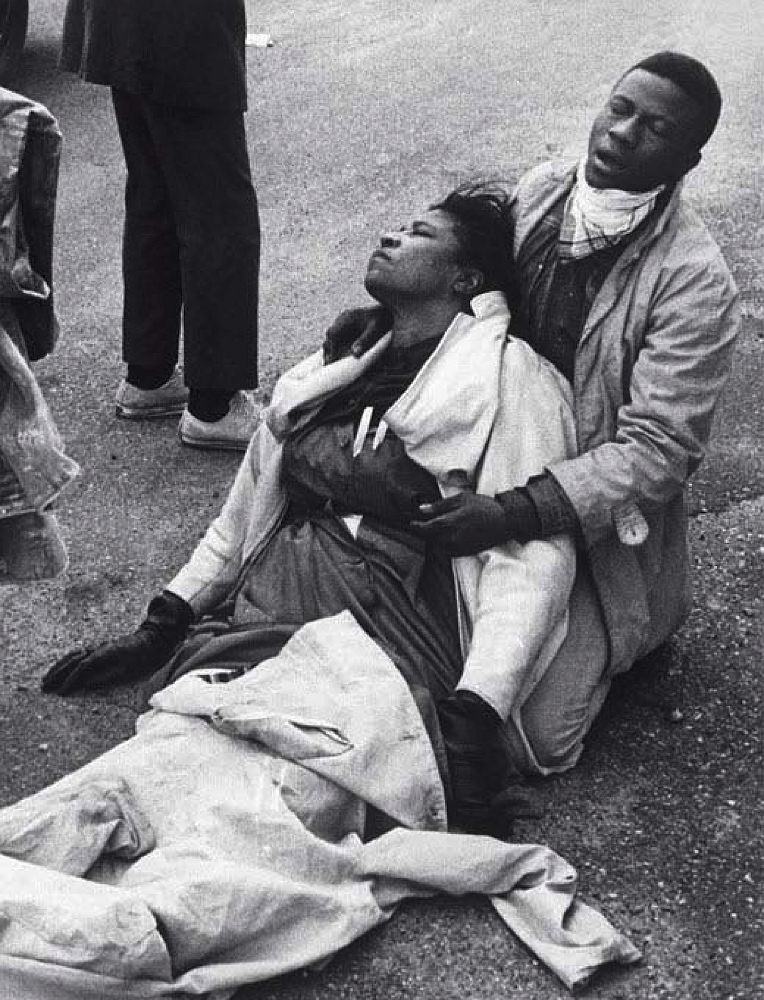

School desegregation: National Guardsman meeting bus at Lamar School, defending against South Carolina anti-integration protests (1970)

The book makes clear why it’s essential to understand the movement as a long, continuing effort. During the past 20 years, a view has taken hold among historians of race in America that the conventional way of framing the movement leaves out its foundations and can lead to wrongheaded conclusions about its purpose. The common alternative is that the movement began in 1954 with the Court’s Brown decision and ended with the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, or perhaps the Fair Housing Act of 1968—a short campaign to end legalized racial segregation. Some use that view as a basis for turning the movement into a quest for colorblindness in American life, rather than for seeing enduring inequities and giving blacks and other subordinated groups equal opportunity, which can require taking account of race.

To believers in the long movement, like Brown-Nagin, it began to form in the 1920s in NAACP lawsuits against racial discrimination and took shape in the 1930s when the South became the center of the battle between whites intent on keeping the country’s elite white, and a racial coalition of progressives committed to expanding access to economic security and social opportunity. As the scholar Jacquelyn Dowd Hall wrote in 2001, “What we need is a narrative of the long civil-rights movement as a project that began in the 1930s and whose end is not yet in sight.”

NAACP pickets against school segregation, St. Louis (1963)

NAACP pickets against school segregation, St. Louis (1963)Photograph by Bettmann/Contributor/Getty Images

The LDF, which led the campaign culminating with the landmark Brown victory, is a central character in Courage to Dissent. Thurgood Marshall, LDF’s director-counsel from 1940 to 1961, personifies the effort. The essence of the Brown case, as he argued before the Court, was that separate schools were inherently unequal—because, he told the justices, the policy of segregation reflected “an inherent determination that the people who were formerly in slavery, regardless of anything else, should be kept as near that stage as possible.” Unanimously, the Court held: “We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place.”

Great black teachers trained outstanding black students in black schools.

Hall wrote, however, that that view of the civil-rights movement “left unquestioned the belief that black schools were categorically inferior.” As a matter of constitutional law, that was the holding, but it eclipsed important realities. Great black teachers trained outstanding black students in black schools. While integration has proven an essential tool in harnessing the capacity of the United States as a diverse society, it has often been an ordeal for black students expected to prove they belong in white cultures. In Atlanta, “the few black students who had experienced school desegregation,” Brown-Nagin wrote, “described a bittersweet encounter, at best.”

The big question Courage to Dissent addressed was: “What would the story of the mid-twentieth-century struggle for civil rights look like if legal historians de-centered the U.S. Supreme Court, the national NAACP, and the NAACP LDF, and instead considered the movement from the bottom up?” Her answer is that “local black community members acted as agents of change—law shapers, law interpreters, and even law makers.”

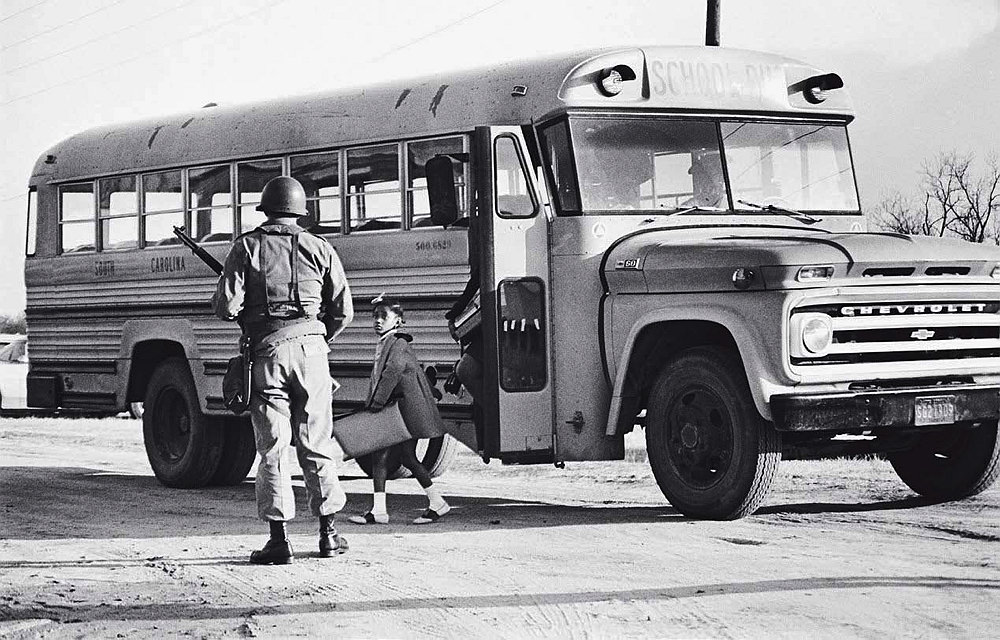

Clarence Ford and his daughters, integrating Simmons Elementary School, Charleston, S.C. (1963)

Photographs by Bettmann/Contributor/Getty Images

Her point is eye-opening: “As important as national organizations and national leaders were, local actors helped to define equality, too—and did so in profound ways. Local actors worked to create the conditions necessary to achieve change.” In a pragmatic approach to civil rights, influential actors “privileged politics over litigation, placed a high value on economic security, and rejected the idea that integration (or even desegregation) and equality were one and the same.” More bluntly, they were willing to compromise with segregationists and embrace “gradualism as the best course for implementing Brown.”

When Brown-Nagin teaches constitutional law, she said, she emphasizes that while the Supreme Court has the power to say what the Constitution means (for example, what public school districts must do to provide equal education to all students), the real meaning of that law depends on how other courts and parts of government interpret and enforce it. How they do that depends on how people outside government understand the Constitution’s meaning. State and local actors, inside and outside government, exercise discretion or influence in ways that can frustrate, advance, or otherwise affect court orders. They become central actors: they determine the law’s effects—how it shapes culture, society, and people’s lives. Brown-Nagin wrote: “Local people—lesser known lawyers and organizers, litigators and negotiators, elites and grassroots, women and men—in interaction with national institutions and leaders, sought to give meaning to the equal protection clause of the Constitution. These actors contested the constitutional conceptions of equality propounded by powerful judges and celebrated lawyers.”

As she was working on the book, an increasingly prominent theme among historians was that social forces were responsible for the end of Jim Crow, not the Supreme Court and other courts. To the Yale legal historian and Bancroft Prize-winner John Witt, Brown-Nagin’s book is “super important” because it provided “a more subtle and better account that law evolved in a kind of dialogue with those forces.” Her accounts of celebrated student protests about segregation in schools, restaurants, and other public institutions illustrated a tactical dimension: how protests were chosen with the goal of changing a specific law.

Brown-Nagin uses the book to spotlight how dissent held peril. Dissenters included leaders in local communities, and non-elites whose limited power made them vulnerable to severe pushback from national leaders, like those of the NAACP. In seeking to preserve community institutions and independence, the local non-elites became agents of more democratic change. Courage to Dissent reveals how they shaped history—and makes clear Brown-Nagin’s independence and creativity as a writer and her courage as a scholar.

The Price of Power

As a young, black NAACP lawyer, Constance Baker Motley, LL.D. ’00, wrote the first legal complaint in the Brown case. She appears in Courage to Dissent after the Supreme Court announced its 1954 decision, when Thurgood Marshall and she filed another, unsuccessful lawsuit. It was on behalf of blacks claiming that they were barred from most public-housing projects in Savannah, Georgia. The book recounts that Motley, then 32, “fiercely opposed Jim Crow with a sense of urgency.” In 1958, she attacked what she called “white supremacy” that impeded desegregation of Atlanta’s public schools. A chapter tells the story of Motley’s uphill struggle as lead counsel in federal court to redress that problem. The story is another that “reveals the limitations of court-centric models of law and social change,” Brown-Nagin writes, because Atlanta “erected an ingenious model of token compliance…but effective resistance to Brown.”

Motley didn’t lead the case to its conclusion. In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated her to be a federal trial judge in Manhattan. By then, she was formidable. As Brown-Nagin writes, wherever Motley appeared in court, she was “striking and audacious” and “captivated and stunned onlookers.” (“When ‘word got out that not only was there a “nigra lawyer”’ but ‘a “nigra” woman lawyer,’” Motley recalled about her first trial in Jackson, Mississippi, “it was ‘like a circus in town.’”) In 1962, a reporter in a Virginia newspaper called her “a prime mover in the cause of civil rights across the nation” and “The Civil Rights Queen.” She became the first black female federal judge in American history shortly before her forty-fifth birthday.

In Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality, Brown-Nagin says that when she wrote about Motley in Courage to Dissent, she was “astounded by how little attention other writers had given her. The relative dearth of coverage struck me as not merely regrettable, but as a kind of historical malpractice. It deprived us of a more accurate and complete history. The invisibility of this fascinating woman in our public histories and popular culture distorts our sense of who rebuilt America.” In Simple Justice, the classic history of the Brown case, the author Richard Kluger mentioned Motley on four of 778 pages, calling her, dismissively, “Pleasant, taciturn Connie Motley.” He quoted an anonymous source making this condescending appraisal: “‘She was a plodder,’ says a colleague of the period, ‘but she knew her stuff.’”

As Brown-Nagin’s corrective book recounts, Motley’s struggle was for her own visibility and equality, as well as every black American’s. [The following sentence corrected December 15, 9:15 a.m.; the text previously stated that Motley was the first black woman to graduate from Columbia Law School.] Motley accomplished a string of firsts, and near firsts, in addition to the federal judgeship: one of the first black women to graduate from Columbia Law School, in 1946. First black woman, second woman, and, for 15 years, the only female lawyer at the NAACP, hired in ’46. First black woman to argue a case before the Supreme Court, in 1961 (she won nine of 10 cases there, from 1961 to 1963). First woman elected to the New York Senate, in 1964. First woman and first black elected Manhattan Borough president, in 1965. First woman to serve as chief judge of the Southern District of New York, in 1982. She took senior status as a judge, or semi-retirement, in 1986 when she was 65 and worked as a judge until she died at 84 in 2005. In 2001, President Bill Clinton awarded her the Presidential Citizens Medal for her “pursuit of equal justice under law.”

Her nomination to the court had triggered extreme opposition on grounds that, as a judge, she would favor the progressive goals she had championed as an advocate. On the bench, she issued major opinions supporting prisoners’ rights, women’s rights, and students’ rights. But she did that as a judicial pragmatist, not as an ideologue or as a result of her racial identity. She embraced what Brown-Nagin called “the familiar, if deeply contested, conception of a judge as a neutral arbiter of apolitical law.” Judge Ray J. Lohier, Jr. ’88, a member of the federal appeals court overseeing the trial court Motley sat on (and a Harvard Overseer), described her in the Columbia Law Review as “a very distinguished district judge and chief judge.”

A vital factor in Motley’s achievement, Brown-Nagin emphasizes, was her “uncommon union” with Joel Motley Jr., her husband of 59 years until she died. (They had one son, Joel Motley III ’74, J.D. ’78.) He “worked as a real estate and insurance broker, eventually becoming a partner in a successful Harlem firm.” He was “quiet,” “unassuming,” and “reserved,” Brown-Nagin writes—“a man who did not wish to dominate or need to compete with her.” His lack of a college degree “belied the egalitarian picture the couple presented to the world,” Brown-Nagin goes on, yet theirs was “an egalitarian marriage decades before the idea captured the American imagination and became the ambition of many working couples.”

Motley was often co-counsel with Thurgood Marshall at the NAACP, and one of her many celebrated clients was the revered civil-rights crusader Martin Luther King Jr. Both men, Brown-Nagin writes, thought her “phenomenally talented.” Their feats, Brown-Nagin reminds, are, “by now standard components of public memory and secondary school curricula.” By contrast, she writes, “far too few Americans today know Motley’s name and deeds.” Brown-Nagin: “Motley’s world-changing accomplishments, which made her a ‘queen’ in her time, should place her in the pantheon of great American leaders.” The main reason she isn’t is that “she was a woman. In Western societies, historical significance is coded male. The lives of men are deemed worthy of study and remembrance.”

The accepted code of style and demeanor for Motley as a working woman reinforced the gap between her broad achievements and the relatively limited recognition she has received until now: “Her persona—reserved, honorable, imperial, and feminine—facilitated her professional breakthroughs in a world premised on masculine norms, steeped in gender stereotypes, and dominated by men habituated to both. But those same traits likely worked against her being widely perceived as a transformational leader in the mold of Marshall and King—talkative, limelight-seeking, charismatic and masculine.”

In the early twentieth century, Motley’s parents, Willoughby Baker and Rachel Huggins, immigrated to New Haven, Connecticut, in their early 20s from Nevis, a Caribbean island in ruins as a sugar-based economy. On the island, her father and others like him were called “Special People” because they were of mixed race and had positions as tradesmen (he was a cobbler) and similar roles in commerce. “In her heart of hearts,” Brown-Nagin writes, “Constance Baker was not like ordinary black folks. Perhaps the most significant fact about her, she often said, was that her parents were not African Americans.”

In New Haven, her father couldn’t get a job repairing shoes and ended up as the steward at Skull and Bones, Yale College’s elite secret society. She was the ninth of 12 children. The family was poor. But it felt rich in pride and culture. “While the Bakers resided near the bottom of the social ladder,” Brown-Nagin writes, “they taught Constance to think of herself as special and raised her to feel superior to others—to African Americans, in particular.”

That feeling helped her cope with mistreatment that was “grossly inappropriate by today’s standards,” Brown-Nagin writes. When Baker was 24 and interviewed with Marshall to be an intern at the NAACP, he showed her “common decency and professional respect,” but “reportedly asked her to climb a ladder next to a bookshelf; he wanted to inspect her legs and feminine form. Baker complied with the request.” Brown-Nagin: “She never publicly accused Marshall of any impropriety; all that she could recall about their first meeting, she later wrote, was Marshall’s ‘total lack of formality’ and his ‘demand’ for informality from ‘everyone in his presence.’” On the other hand: “Without Marshall’s generosity of spirit and openness to hiring a woman, Baker often said, she ‘would not have gotten very far as a lawyer,’ for ‘women simply were not hired in those days.’”

Exploring challenges in Motley’s life and how she responded, Brown-Nagin had in mind challenges of women today, black women especially—including herself. The book is a scrupulously researched study in power—about “law versus political power as a tool of change,” as Courage to Dissent was, and about “how gender—mediated by race and class—shapes life trajectories.” Brown-Nagin observes, “Motley’s gender, embodied as black and working class, makes her story of ascent especially intriguing”—to readers, Brown-Nagin rightly believes, but also to herself as a highly successful black woman from the working class.

The spirit of the book is rooted in “a theme embedded in” the work of the great American writer James Baldwin. Brown-Nagin quotes him and comments on her own book: “‘What is the price of the ticket?’ The questions underpinning Civil Rights Queen are all about outsiders and power. How do outsiders—women, in particular—gain power, with what benefits, and at what costs? How does access to power shape and change individuals who initially sought it because of a commitment to social justice?”

Brown-Nagin sums up about Motley: “She grabbed opportunities and endured challenges without making much fuss. Along the way, racism and sexism beset her, just as they linger and disadvantage women and people of color today. Motley benefited from good fortune and experienced bad luck. She cultivated male and female sponsors and encountered male and female detractors. Sometimes she grew weary, even sad. Through it all, Constance Baker Motley kept moving.” She “shook up the world.”

Civil Rights Queen includes a remarkable strand of autobiography. Brown-Nagin writes that the questions raised in the book “remain relevant today”—“about the purposes and limits of power when wielded by talented agents of change on behalf of marginalized people.” About Motley and, indirectly, herself, she concludes: “her story also challenges the enduring fiction that pure talent best explains who succeeds in life, or that discrimination alone explains who does not. Motley’s is a story about both talent and the structures of inequality, but it is not only about these critically important factors. It is a window onto how a woman’s mindset in the face of inequality and her choices about how to publicly perform her identity positioned her in an unequal world.”