Julian Breece ’03 remembers feeling haunted by a picture on the wall of his childhood home in Washington, D.C.—a photograph of Alvin Ailey, signed by the legendary choreographer himself: “To Lynne, who should be with us.” As a young woman, Breece’s mother had been a dancer in Ailey’s main touring company, but after two years she decided to quit and go back to college. She felt pressured, Breece says, to follow a more traditional path: marriage, children, a steady job. She earned a graduate degree and became a public-school therapist, married Breece’s father, a lawyer, and had a family. Their life together was happy, Breece says, but she never forgot Ailey and the possibilities she’d left behind. “She kept that picture up, and it’s something she always thought about,” he says. “I think that’s why she pushed my brother and me to pursue our dreams, whatever they were.”

For Breece, the dream turned out to be screenwriting. After Harvard, he earned a master’s in film producing at the University of Southern California, and in the 15 years since, he’s written (and sometimes directed or produced) works in a range of genres and formats: drama, science fiction, sitcoms, animated web series, feature-length films, 15-minute shorts. In 2019, he was a co-writer for the Emmy-nominated Netflix miniseries When They See Us, about the five black and Latino boys falsely accused of rape in the 1989 Central Park jogger case. He also wrote the script for a biopic about Ailey, directed by Oscar-winner Barry Jenkins (it’s now in post-production). Breece remembers finding a recording of one of his mother’s performances deep in the archives during the research for that film (“which was amazing and wonderful”) and seeing her name on old posters and advertisements.

His longest-running project—opening in theaters (and then on Netflix) later this year—is a film called Rustin, on the life of civil rights leader Bayard Rustin. An organizer of the Freedom Rides and the Montgomery bus boycott, he was a crucial architect of the 1963 March on Washington, and mentored Martin Luther King Jr. in Gandhian nonviolence. But Rustin was also openly gay, long before it was socially or legally accepted, and so he often stayed behind the scenes. Eventually, he “faded from the shortlist of well-known civil rights lions,” as one Washington Post reporter put it.

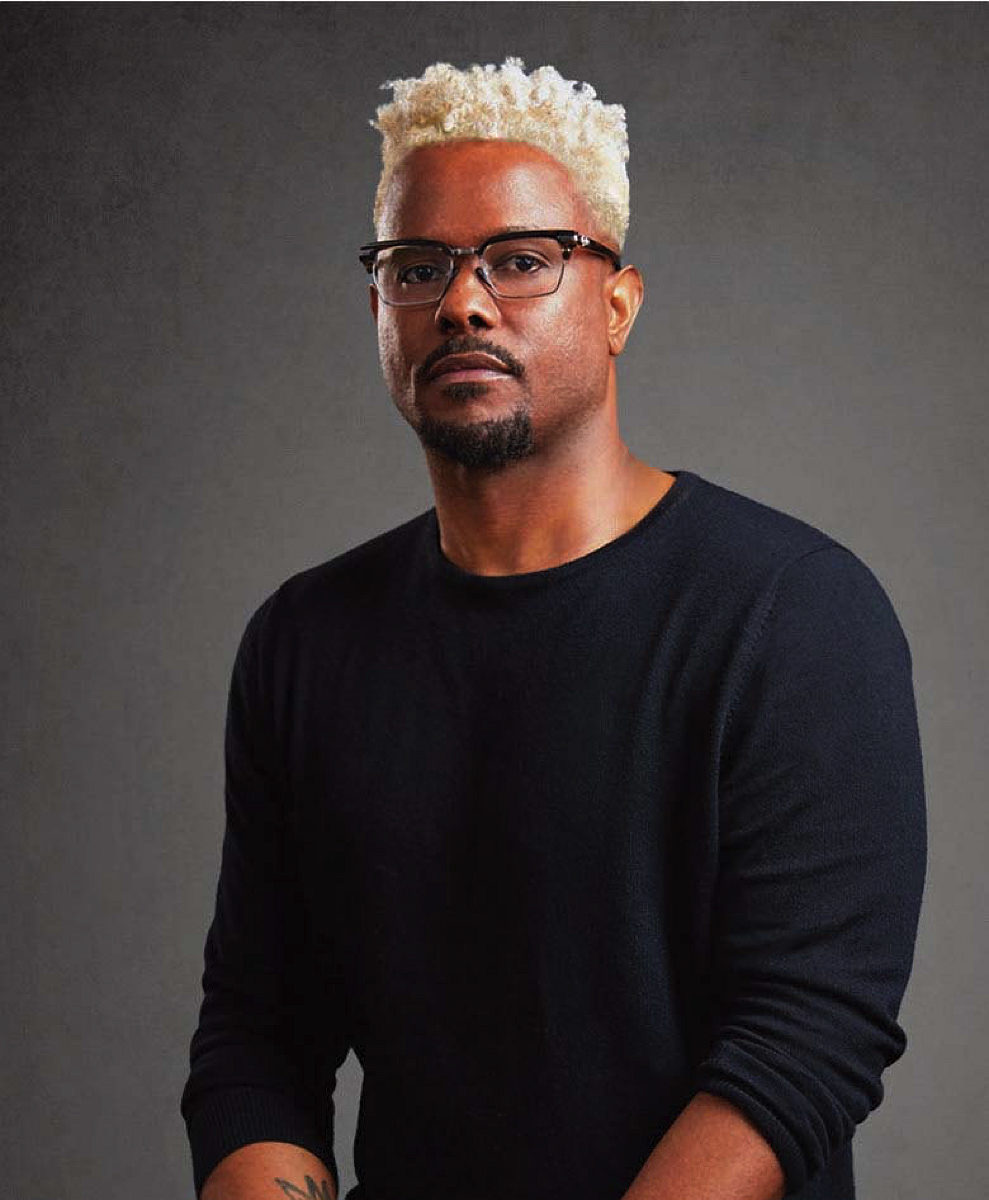

Julian Breece | Photograph by John Keifer

But Breece knew Rustin. “I’d studied him in college,” he says. And as a gay black man himself, “I knew his story and connected with him. He’s a hero of mine.” In 2013, when Breece heard that Dustin Lance Black (best known for his Oscar-winning screenplay for Milk, about gay-rights activist and politician Harvey Milk) was seeking a writer for a film about Rustin, “I wrote this long letter about how passionate I was about the project.” It felt like a long shot—Breece was then barely established in the industry—but he got the job.

He dove into the research, interviewing anyone he could find who’d worked with Rustin (who died in 1987); he also spoke to Rustin’s friends and loved ones, and his partner, Walter Naegle. He combed through the footnotes of biographies, looking for primary sources of information. “We knew we were doing a Bayard Rustin movie,” he says, “but it was kind of my job to find the movie.” The best biopics, he believed, captured the essence of a historical figure, rather than trying to encompass too much. “At the center of the film, you need a relationship,” Breece says. “If you can find a pivotal moment in the person’s life, or a relationship that changed them, that’s where your story is.” Rustin’s narrative unfolds around the lead-up to the March on Washington, and a series of relationships: romances with fellow civil rights activists, both black and white, and Rustin’s deep, complicated friendship with King.

To Breece, this film feels like a return to his roots, and to the kinds of stories he was drawn to as a young screenwriter still trying to break into the business. His first script, Ball, never produced, was about the queer black and Latino ballroom scene in New York City. His earliest acclaim came with The Young & Evil, a short selected for the 2009 Sundance Festival, which grappled with existential questions about HIV and homosexuality. Rustin, he says, is “a return to that place of curiosity, of writing from the soul rather than from the head.” His upcoming projects have that too, including a Hulu miniseries with director Lee Daniels on Sammy Davis Jr., and a film Breece is writing and directing on the origins of House music in the 1970s and ’80s at a black gay nightclub in Chicago called Warehouse. “These are stories I’m excited to tell,” he says.

Breece has been telling stories for as long as he can remember: as a child, he drew cartoons of his family and took theater classes, which led to a brief stint as a working actor, in productions at the Kennedy Center and on Teen Summit, a BET talk show. But his mainstay was always writing. When he was six, his best friend’s mother died, leaving him shaken, and Breece wrote a short story in which his friend went searching for her across a supernatural landscape. “I was sort of negotiating loss in my head.” In high school, Breece invented “fantasy stories” about himself and his classmates: “Very soapy and messy,” he says. “The most aspirational versions of our lives.”

At Harvard, Breece concentrated in history and literature and African and African American studies, served on The Advocate’s fiction board, and wrote for a now-defunct magazine called Diversity and Distinction. Most importantly, he took a creative writing class from Jamaica Kincaid, professor of African and African American studies in residence, who kept reminding students that the “real work” of creativity happens far from the classroom. “She said, ‘I want you to run away, go overseas on a moment’s notice, make love to a beautiful woman or a beautiful man,’” Breece recalls. “She really encouraged us to live, to expand our consciousness.”

Reading Kincaid’s work—and that of poets like Carl Phillips ’81, Rita Dove, and Jorie Graham (the Boylston professor of oratory and rhetoric)—helped sharpen his screenwriting. “I always think of these characters as real people,” Breece says. “And real people don’t say what they mean.” Poetry’s depth and concision taught him to “keep as much white space on the page as possible.” Breece describes one of the scenes he’s proudest of in Rustin in which the civil rights activist boards a bus in Tennessee and refuses to sit at the back. He’s confronted and hauled off by police officers, who beat him to the ground repeatedly, until he’s bleeding. One of the few lines of dialogue is spoken by a white mother, who calls Rusin a slur and tells her son not to touch him. Rustin never speaks, and the officers pummel him wordlessly. The woman falls silent too, “And you see something change in her, watching this man be brutalized,” Breece says. “It’s this moment of raw, exposed humanity, the visual force of what Bayard and the work he was doing represented. Witnessing what he was putting his body through in order to be seen as human—that changes people.”