“These are complicated days,” said Howard Georgi, Mallinckrodt professor of physics, on Tuesday morning, as he welcomed the audience in Sanders Theatre to the 231st Phi Beta Kappa (PBK) Literary Exercises, which marks the traditional start to Commencement week. In their own later remarks, the ceremony’s two speakers—poet Natalie Diaz and orator Adam Falk—gave concrete shape to some of those complications, both personal and political, emotional and intellectual.

The Teaching Prizes

After Matthew Potts, Pusey Minister in the Memorial Church and Plummer professor of Christian morals, gave an invocation calling on “the spirit of wisdom to be with us in this place,” Logan McCarty, secretary of the PBK Alpha Iota chapter at Harvard (and assistant dean of science education and lecturer on physics and on chemistry and chemical biology), presented three honorees with Phi Beta Kappa Teaching Prizes. Nominated by the society’s undergraduate members and selected by its undergraduate marshals, they were:

• Kelly McConville, senior lecturer in statistics and co-director of undergraduate studies in statistics, who, McCarty said, quoting the citation, “single-handedly revitalized Statistics 100 to one of the most important introductory courses in that field” and “encourages students to ask questions freely, no matter how basic or seemingly obvious.” Her teaching extends beyond the lecture hall, to academic advising and undergraduate research groups.

• Curtis McMullen, Cabot professor of mathematics, who, McCarty reported, “has a rare gift for effectively communicating complex mathematical concepts with unparalleled clarity and enthusiasm.” A winner of the Fields Medal (often considered the Nobel Prize for mathematicians), he has a “genuine passion” that McCarty called “contagious” and fosters strong relationships with students, many of whom follow him into the field.

• Justin Weir, Reisinger professor of Slavic languages and literatures and professor of comparative literature, whose courses explore the moral inquiries in authors like Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky. Weir, McCarty said, “created a framework to study ethics through the lens of literature and forced students to rethink their moral and intellectual priorities.”

The Poet: “A Practice of Attention and Intention”

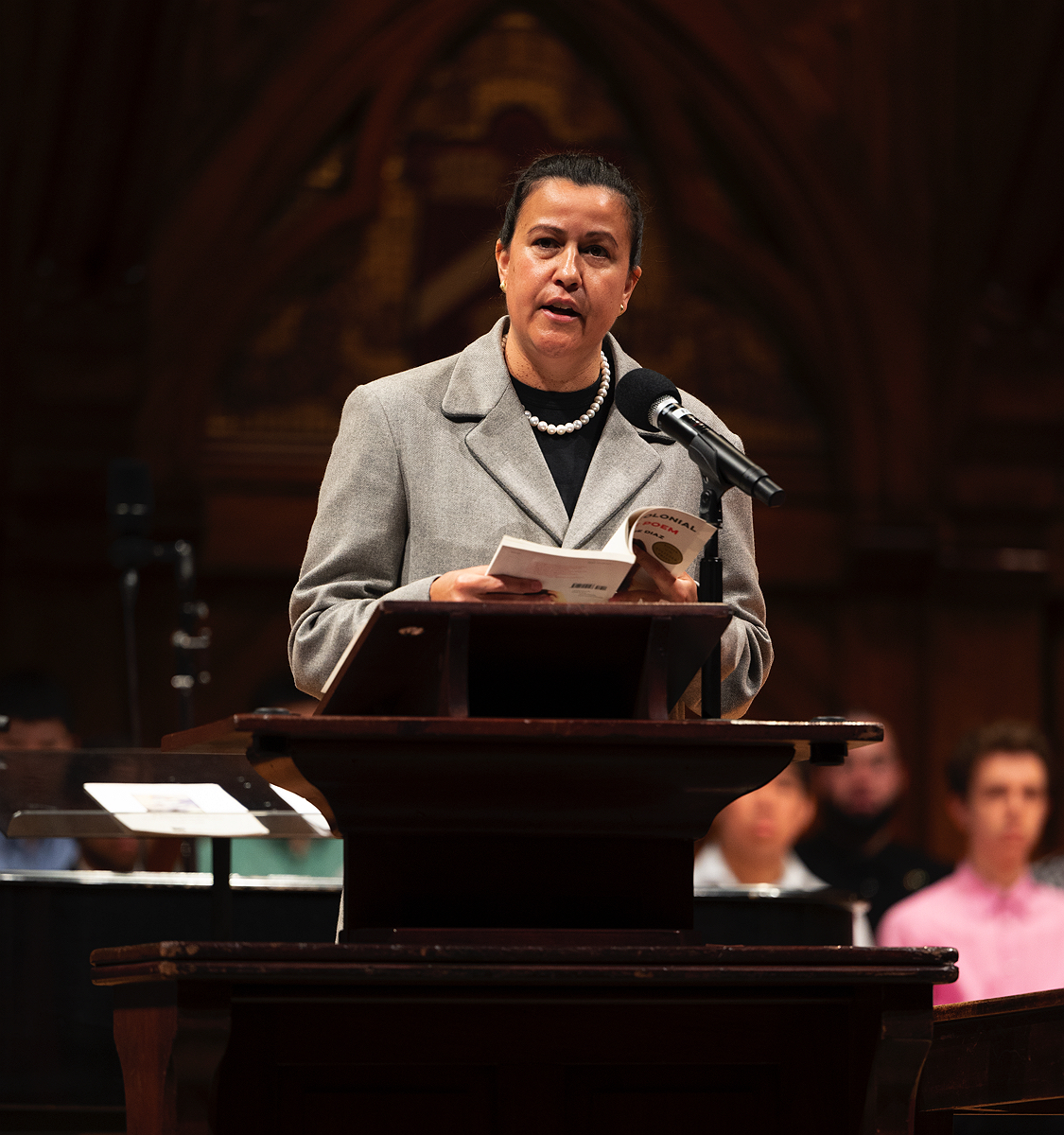

Before she was a writer, Natalie Diaz was a basketball player. And a good one: she earned a full athletic scholarship to Old Dominion University in Virginia (where she and her teammates reached the NCAA tournament final her freshman year) and then played professionally in Europe and Asia. And before that, she was born and raised in the Fort Mojave Indian Village in Needles, California, on the banks of the Colorado River. She is Mojave and an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Tribe, as well as the daughter of a Mexican father. All of these elements shape her poetry, which explores (and often interrogates) cultural histories, family dynamics, individual passions, and national mythologies. After basketball, Diaz returned to her alma mater for an MFA in 2007, and she is now an associate English professor and chair of modern and contemporary poetry at Arizona State University. In 2018, she won a McArthur Fellowship, and in 2021, her second book of poetry, Postcolonial Love Poem, won the Pulitzer Prize.

Natalie Diaz

Photograph by Jim Harrison

In remarks introducing the three pieces she read on Tuesday—“Postcolonial Love Poem” and “The Mustangs” from Postcolonial Love Poem, and “I Watch Her Eat the Apple” from her first collection, When My Brother Was an Aztec—Diaz described poetry as “a practice of attention and intention, of understanding the power of story, of how story holds us, and how we hold others in it, whom we include or leave out, whom we let fall or pick up.”

Diaz’s poetry pays particular attention to language—its power and vulnerabilities, its violence and contradictions—and she often talks about it in almost physical terms, as an energy, a “happening.” She speaks Mojave, English, and Spanish, languages that are constantly in tension, belonging to both colonizers and the colonized. On Tuesday, she described language as “a way we carry our bodies to one another” and spoke of poetry as being “like basketball to me” (a meaningful analogy, given that she played the game for most of her life). Basketball and poetry both “shaped the way I dream and imagine,” she said, “the way I fight and love. Poetry is where I can love who and what are most difficult to love in this world. It is a place where I can hold my brother, who is an addict. It is a place I can hold a country that has done its best to erase me and my people….It is a place where I can treat every body—the body of the river, of land, the body of my brother, a lover, my strangers and my enemies—as the body of the beloved.”

“Postcolonial Love Poem” begins this way:

I’ve been taught bloodstones can cure a snakebite,

can stop the bleeding—most people forgot this

when the war ended. The war ended

depending on which war you mean: those we started,

before those, millennia ago and onward,

those which started me, which I lost and won—

these ever-blooming wounds.

In “The Mustangs,” a prose poem, Diaz conjures up her brother and his varsity high school basketball team. “One of the hardest things in my life is that I have a brother who, in my every day, I’m not able to hold close,” she told the audience. In some way, poetry restores that closeness; it is “a place where I can look at my brother and love him in ways I can’t in my every day.” Told from the perspective of a little sister watching from the “rattling bleachers of the Needles Mustangs gymnasium” as AC/DC roars over the loudspeakers and her brother and his teammates—“young kings and conquerors”—warm up before a game, the poem begins with an achingly poignant line: “In another life, my older brother was a beautiful, muscular boy who could jump from a standing position to grab a missed shot right from the rim.” Three stanzas later, she concludes:

They made layup after layup, passed the ball like a planet between them, pulled it back and forth from the floor to their hands like Mars. “Thunderstruck” played so loudly that I couldn’t hear what my mother hollered to my cheer my brother—I could only see her mouth opening and closing. I was ten years old and realized right there on those bleachers thundering like guns that this game had the power to quiet what seemed so loud in us—that it might have the power to set the fantastic beasts trampling our hearts loose. I saw it in my mother, in my brother, in those wild boys. We ran up and down the length of our lives, all of us, lit by the lights of the gym, toward freedom—we Mustangs. On those nights, we were forgiven for all we would ever do wrong.

The Orator: Free Speech as “A First Loyalty to Our Academic Disciplines”

In his remarks, Adam Falk, Ph.D.’91, a theoretical physicist and president of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, gave a passionate defense of academic freedom. A former president of Williams College and a former dean at Johns Hopkins University, he called on graduates to push back against the threats to academic freedom, and to remember the powerful values that bind scholars to each other and to the academy: “a first loyalty to our academic disciplines—not to our governments, nor to our employers, but to our disciplines.” That loyalty is what makes possible the exchange of ideas that ensures a healthy academic community and enables academic institutions to contribute to society.

Falk called out three “recent and very troubling” developments jeopardizing academic freedom in Florida: a November 2021 incident in which the University of Florida prohibited three political science faculty members from giving expert testimony in a voting rights lawsuit against the state; the “infamous Stop WOKE Act,” which forbids professors and teachers from discussing certain ideas (chiefly, that systemic injustices exist in American society); and the takeover earlier this year of a small liberal arts college, New College of Florida, by Governor Ron DeSantis, J.D. ’05, and the state legislature.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Photograph by Jim Harrison

“The extraordinary claim that lies at the heart of all three of these cases is that the loyalty of faculty must be to the state, not to their disciplines, and the state may decide what they are permitted to say in the classroom and the courtroom,” Falk said. “There is perhaps no idea more antithetical to academic freedom, or to the academy itself. It is certainly a notion favored by history’s authoritarians.”

Falk drew an explicit link between “draconian steps” like those recently undertaken in Florida and the plight of endangered artists and academics around the world who are invited to Harvard each year as fellows in its Scholars at Risk program. And “as it happens,” he added, “such a story runs through my own family.” Falk is the son and grandson of scholars who fled Nazi Germany. In 1933, when Adolf Hitler’s National Socialists came to power, Falk’s father was a 27-year-old professor at the German School for Politics in Berlin. He had traveled to Austria that March, during spring break, “and while he was gone,” Falk said, “there came the Reichstag fire, the banning of other parties, and the establishment of the dictatorship. My father understood that the Nazis would not allow independent academic institutions to persist, that in fact the notion of an independent academic institution was anathema to their conception of the role of the state in society. He never returned to Germany.” By the end of 1933, the only faculty who remained at his university were those “prepared to serve as voices of the Nazi state.”

His father’s experience, Falk said, “is a chilling reminder of the importance of academic freedom, and a reminder that the destruction of a society’s political freedoms often starts by targeting the universities. Academia, as an institution, is a bulwark against the idea that the state can decide what is acceptable to say, write, and even think.” To the graduates, he said, “Your membership in Phi Beta Kappa gives you the opportunity and, I would say, the obligation, to defend the academic freedom you have so fully embraced in these years at Harvard.”