In the autumn of 1924, Alain Locke was enjoying the beauties of San Remo, Italy. But his mind and heart were back home in the United States—specifically, in Harlem, which was fast becoming the unofficial capital of black America. Locke—A.B. ’08, Ph.D. ’18—39 years old and a professor at Howard University, had been a leading light of the African-American intellectual world for almost 20 years, ever since he became the first black student to receive a Rhodes Scholarship. Now he was engaged in guest-editing a special issue of a magazine called Survey Graphic that would be devoted to Harlem. He enlisted as contributors some of the nation’s leading scholars and creative writers, black and white—from the historian Arthur Schomburg and the anthropologist Melville Herskovits to the poets Countee Cullen and Claude McKay. The issue was shaping up to be a major event: a quasi-official announcement of what would come to be known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Now, vacationing in Italy, Locke set to work on his own contribution, an essay that would explain the meaning of this cultural moment. Like so many American writers, he found that being in Europe freed him to think in new ways about his country. (In the same year, Ezra Pound moved to Rapallo, where he would carry on his campaign against the status quo in American poetry.) The Harlem Renaissance, for Locke, was another expression of the modernist spirit; and modernism was a revolution in society as well as in art. For black America, it took the form of an intellectual liberation that, he believed, would be a precursor to social change.

The title of Locke’s essay, “The New Negro,” heralded that revolution. “The younger generation,” he announced, “is vibrant with a new psychology, the new spirit is awake in the masses.” The key to this newness, he argued, was a rejection of the old American way of thinking which made “the Negro...more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place’, or ‘helped up.’” Rather than being the object of others’ discourse, African Americans—and particularly, for Locke, African-American artists and intellectuals—were insisting on what a later generation would call “agency,” the right to be the protagonists of their own history. “By shedding the old chrysalis of the Negro problem,” Locke wrote, “we are achieving something like a spiritual emancipation…the decade that found us with a problem has left us with only a task.” With the Survey Graphic issue—which would later be expanded into a landmark book, The New Negro—Locke was positioning himself as the philosopher and strategist of a movement.

But while Locke would go down in history as the dean of the Harlem Renaissance, his own work and personality are more obscure than those of the creative writers he mentored and sometimes fought with: now-canonical figures like Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. While Locke played a key role in African-American life for five decades, that role was usually behind the scenes, as editor, curator, teacher, and impresario. His essays and lectures helped shape cultural debates, but he never produced a major book of his own. After his death in 1954, his reputation inevitably began to fade.

Fortunately, Locke’s achievement—and what is still more fascinating, his complex and contradictory personality—can now be appreciated in full, thanks to a monumental new biography. The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke, by Jeffrey C. Stewart, a professor of Black Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, weighs in at more than 900 pages, and recreates Locke’s life and times in exceptional detail. Drawing extensively on Locke’s correspondence and archive, and offering a richly informed portrait of his milieu, The New Negro is a major biography of a kind that even writers more famous than Locke are lucky to receive.

The man who emerges from Stewart’s book was, like all the most important thinkers, complex and provocative, a figure to inspire and to argue with. At first sight, Locke’s focus on culture and the arts as a realm of African-American self-making may seem to be less than urgent. When we are still struggling as a country to accept the basic principle that Black Lives Matter, do we really need to read Locke’s reflections on painting and sculpture, music and poetry? This was the very critique he faced from many in his own time—militant activists like W.E.B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. ’95, for whom Locke’s aestheticism seemed a distraction or a luxury.

But Locke strongly rejected such a division between art and activism. Working at a time when the prospects for progress in civil rights seemed remote, Locke looked to the arts as a crucial realm of black self-realization. “The sense of inferiority must be innerly compensated,” he wrote; “self-conviction must supplant self-justification and in the dignity of this attitude a convinced minority must confront a condescending majority. Art cannot completely accomplish this,” he acknowledged, “but I believe it can lead the way.”

It was because he had such high hopes for black art that Locke argued for the separation of art from propaganda. This, for him, was part of the point of the Harlem Renaissance, whose experimental aesthetics often alienated conventional taste, both black and white. “Most Negro artists would repudiate their own art program if it were presented as a reformer’s duty or a prophet’s mission,” he wrote in one of his most important essays, “Beauty Instead of Ashes.” “There is an ethics of beauty itself.” Locke’s idea of beauty tended to be classical and traditional—he was wary of popular arts like jazz and the Broadway musical—but his faith in the aesthetic was quietly radical.

Indeed, long before terms like postmodernism and postcolonialism came on the scene, Locke emphasized the way racial identity was imagined and performed, not simply biologically given or socially imposed. He drew a comparison between the situation of African Americans and those of oppressed people like the Irish and the Jews, seeing in the Celtic Revival and Zionism models for a spiritual self-awakening that would have real-world results.

Yet Locke’s own experience of race in America convinced him that there was no possibility of cultural separatism. He was an early and powerful advocate for an idea that is now universally accepted: that black culture was not separate from American culture, but constitutive of it. “What is distinctively Negro in culture usually passes over by rapid osmosis to the general culture,” he observed. “Something which is styled Negro for short, is more accurately to be described as Afro-American.” Locke thought as deeply as anyone has about what it meant to be “Afro-American”; and the origins of that thought can be traced to his years at Harvard, both inside and outside the classroom.

Alain LeRoy Locke arrived at Harvard in 1904 as a 19-year-old freshman, and immediately fell in love. “It’s a beautiful place,” he wrote to his mother, Mary. “Everything is old and staid….The largest finest trees I have ever seen and the campus full of pigeons and squirrels. Neither seem to mind passers by.” Like many a student before and since, Locke was awed by the sense of connection with the American past that Harvard offered: “You can’t imagine the historical associations of this place. I have to cross the field where the men assembled for the battle of Bunker Hill every day.” The academic life of the College suited him equally well. It was one of the golden ages of Harvard’s history, and Locke, a student of philosophy, relished the opportunity to study with figures like Josiah Royce and George Santayana. Looking back on his college years decades later, Locke summed up what Harvard meant to him: it was the place where he “gave up Puritan provincialism for critical-mindedness and cosmopolitanism.”

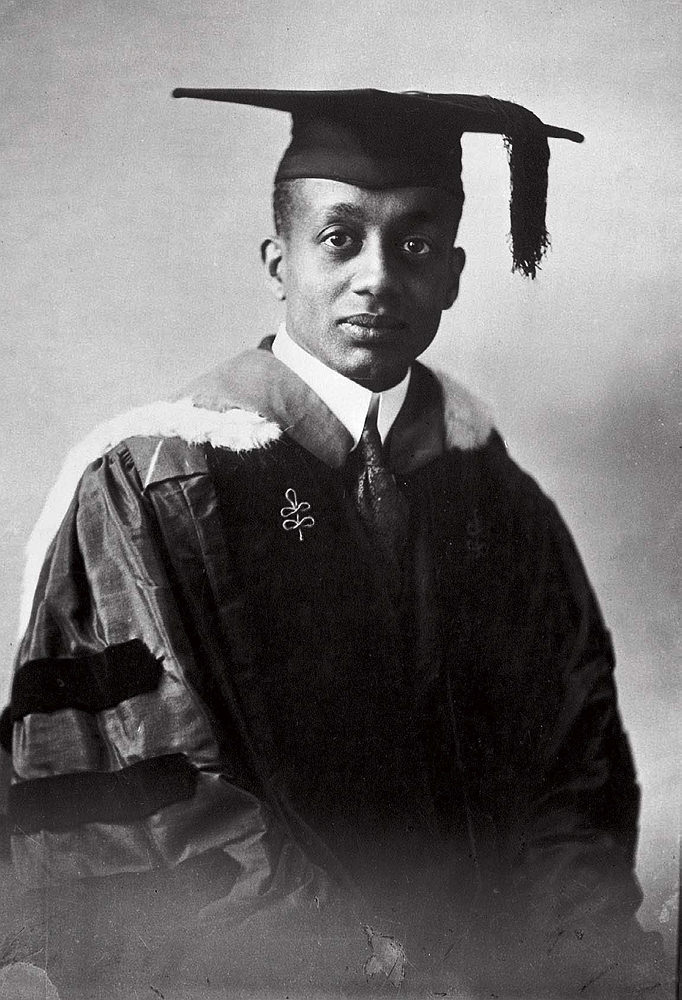

Locke earned his Harvard doctorate in 1918. His dissertation examined "The problem of classification in theory of value."

Photograph courtesy of Moorland-Spingarn Research Center/Howard University

That provincialism was a product of what Stewart calls, in one chapter title, “A Black Victorian childhood,” at the heart of Philadelphia’s African-American elite. This was an elite with little money or power, but with a strong class consciousness and high intellectual expectations, particularly in Locke’s own family. His ancestors were prominent members of the city’s free black community: his maternal great-grandfather was a naval hero in the War of 1812, while his father’s father was a teacher at the Institute for Colored Youth, founded in 1837 as one of the first American schools for black students. Locke’s father, Pliny, was the first black civil-service employee in the U.S. Postal Service. Stewart quotes an obituary that describes Pliny Locke as “born to command...All of his teachers conceded to him a wonderful mind and felt that had he been at Harvard, Yale or any of the great institutions of learning, he would have been in the forefront of the strongest.”

Pliny died when Alain—known in his childhood as Roy—was eight, leaving him to be raised by Mary, a schoolteacher. Stewart writes that the relationship with his mother was by far the most important of Locke’s life. She provided him with the profound self-confidence he needed to succeed in a society built on racism and segregation. And Locke had a further challenge to negotiate when it came to his sexuality: he was gay, a fact known to his friends, though he could never allow it to become an official part of his identity. If Locke managed to build a highly successful public career despite these challenges, it was due in no small part to his mother’s support. No wonder he kept her as close as possible, writing to her constantly when he was at college, and bringing her to Washington, D.C., to live with him as an adult. He never recovered completely from her death, in 1922.

Central to Stewart’s understanding of Locke is that the Black Victorian ethos of his childhood—the stress on propriety, achievement, self-sufficiency, and high culture—was both indispensable for his success and a barrier to full self-realization. In Stewart’s view, Locke had internalized the idea that “gentlemanly culture would override racism.” In the elite white educational institutions where he flourished, like Central High in Philadelphia and then Harvard, this idea had a semblance of truth. “There is no prejudice here,” Locke wrote his mother soon after arriving in Cambridge. He was happy to find that the Cambridge boarding houses did not discriminate against him, as he evidently expected they would: “What do you think? Every single one but one was pleasant and offered me accommodations.”

But in the broader American context, the idea that Locke could escape racism through personal achievement was, in Stewart’s words, a “cruel myth,” and one that took a psychological toll. This was evident even at Harvard, where Locke made several close white friends but kept a conspicuous distance from other black students. (Senior album photographs of the time suggest that three to six African Americans entered each year: less than 1 percent of each class.) “They are not fit for company even if they are energetic and plodding fellows,” he wrote his mother after being introduced to a group of “colored” students. “I’m not used to that class and I don’t intend to get used to them.” Such anxiety suggests that his sense of fitting in at Harvard was brittle, provisional. Stewart writes that, at this time of his life, “Locke believed race was essentially a performance.” This was psychologically liberating, since it gave him a feeling of being in control of his own destiny. But at the same time, it left him feeling perpetually on-stage, afraid of making a wrong move. “It’s well enough for them to get an education but they are not gentlemen,” Locke wrote about his fellow black students, and it was crucial to his self-image that he be recognized as a gentleman.

Another reason for avoiding the company of other African-American students, Stewart observes, was that he was “a closeted queer student in an aggressively heterosexual Black student community.” He was more at ease with a handful of white students who, like him, expressed their sexual identity by cultivating the period’s high aestheticism. He was especially close to a fellow Philadelphian named Charles Dickerman: “they were likely lovers by the end of Locke’s Harvard years,” according to Stewart. Locke told his mother of one evening spent in Dickerman’s room listening to his friend read a play by the Irish poet W.B. Yeats, while Japanese incense burned. “I was a little bored,” he confessed, but in such settings, Stewart writes, “homosexual desire was beginning a slow process of intellectual growth.”

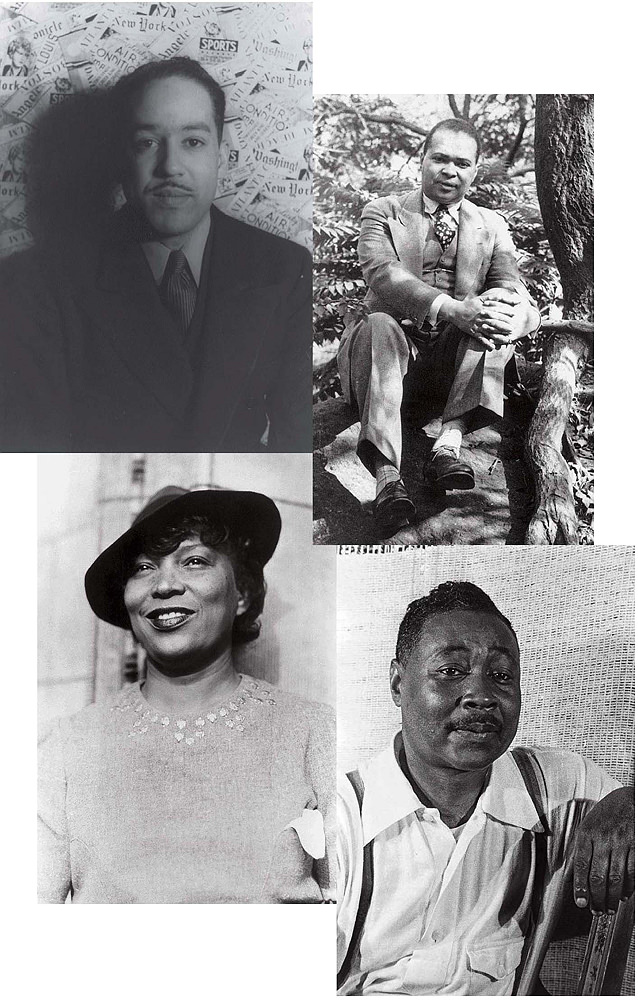

Locke's fellows in the Harlem Renaissance included (clockwise from top left) Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Claude McKay, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Photographs (clockwise from top left) courtesy of the Library of Congress; History Images/Alamy Stock Photo; Everett Collection Inc./Alamy Stock Photo; courtesy of the Library of Congress

Locke soon grew into a star student. What’s more, he was ”a master of the academic game in which letters of introduction, flattery, and genteel self-presentation were essential to being taken seriously by the ‘great men’ at Harvard.” He visited Josiah Royce, the eminent philosopher, at his home at 103 Irving Street, and charmed him: “He said...he would like to personally advise me on any point in my work—that he hoped to see me in his higher philosophy class,” Locke wrote proudly to his mother. He accumulated honors, including the Bowdoin Prize for an essay on “Tennyson and His Literary Heritage.” And he managed all this while living on the tightest of budgets—whatever his mother could spare from her schoolteacher’s salary.

The most important influence on Locke, however, was not a philosopher but a professor of comparative literature, Barrett Wendell: “I see that I am a spiritual son of Barrett Wendell’s,” Locke reflected later in life. In Wendell’s course English 46, Locke was exposed to a new way of thinking about high culture, not as a universal pantheon of great men and great works, but as the distinctive expression of diverse national traditions. A writer did not become a classic by escaping his nationality or his race, but by expressing them in a way that spoke to all of humanity. This was the idea informing the literary movements that emerged across Europe in the late nineteenth century, the great age of nationalism.

For Locke, the application of this idea to black American culture was electrifying. This is already clear in the first piece in Locke’s collected works, a lecture he delivered in 1907 to the Cambridge Lyceum. His subject was the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, a pioneering African-American writer who had died the previous year at the age of 34. Locke’s high aesthetic standards did not allow him to praise Dunbar unreservedly: “There have been greater writers than Dunbar of Negro extraction,” he noted. But Dunbar was historically significant, Locke argued, as an “exponent of the American Negro life in poetry.”

Dunbar, that is, embodied the genius and experience of his race, in just the way Yeats did for the Irish. In doing so, he helped build an African-American cultural tradition that would both strengthen its possessors and enrich world culture. For it was culture, not color, that defined race, Locke insisted. “I do not think we are Negroes because we are of varying degrees of black, brown, yellow, nor do I think it is because we do or should all act alike. We are a race because we have a common race tradition, and each man of us becomes such just in proportion as he recognizes, knows, and reverences that tradition.”

Here was the definition of race that would inform Locke’s work down to “The New Negro” and beyond. For if race was a tradition, rather than an identity, it stood to reason that it was the creators and guardians of that tradition—the writers, painters, sculptors, musicians, and actors—who should stand at the forefront of African-American life. In this way, Locke invented a leadership role for himself in the black community. Unequipped to be a political intellectual or popular leader, on the model of Booker T. Washington or W.E.B. Du Bois, Locke argued that the aesthete had just as much to contribute.

But it would be years before Locke emerged as a leader of the Harlem Renaissance, and his education was not yet complete when he graduated from Harvard a year ahead of his class. In his senior year, he decided he would try for a Rhodes. The program had begun just five years earlier, and the scholarship had not yet been awarded to an African American. Locke’s mother doubted that it ever would be: “I don’t know why you are applying for that Rhodes thing. You know they will never give it to a Negro,” she told him. Indeed, Stewart shows that not everyone at Harvard wanted Locke to succeed. One dean failed to send a required letter to the Rhodes committee, and even Locke’s mentor Barrett Wendell confided years later that he believed Locke’s application was “an error of judgment,” on the openly racist grounds that no African-American candidate could be “widely, comprehensively representative of what is best in the state which sent him.” (Luckily, Locke didn’t ask Wendell for a recommendation.) There were other obstacles, too: at four feet, 11 inches, and under 100 pounds, Locke was clearly not the athlete that the committee typically looked for.

Undaunted as always, Locke applied, and passed the initial qualifying exams. Next he had to decide which state competition he would enter. His mother lived in New Jersey, and his current residence was Massachusetts; but in those states he would be going up against graduates of Princeton and Harvard, making it a tougher climb. Instead, Locke decided to list his aunt and uncle’s address in Philadelphia as his home, as he had done when he applied to Harvard. “I shall try and try hard, and the Pennsylvania Committee will see that one negro has the nerve and the backing to thrust himself on their serious consideration if but for a few hours,” he vowed. His interview and academic record said all that was necessary, and Locke was chosen unanimously. Later, a legend arose that Locke did not appear before the Committee in person, and that they awarded him the scholarship not knowing that he was black. But Stewart shows that this was not the case: “the Committee knew Locke was Black and had decided to make a statement for racial justice.”

Locke’s triumph as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar made national headlines, and turned him into a celebrity in the black community. It also, predictably, provoked racist opposition from some people at Oxford, including Rhodes Scholars from the southern states, who saw Locke’s inclusion in their ranks as a grievous breach of the rules of white supremacy. The British administrators of the Rhodes Trust considered revoking Locke’s award, but decided it was impossible, in part because it would “bring up the colour problem in an acute form throughout our own Empire.” Still, all of Locke’s preferred Oxford colleges refused to admit him; finally, the Trust had to intervene to ensure that he was admitted to Hertford College. And the southern Rhodes Scholars boycotted Locke at Oxford, refusing to invite him to official functions or to attend receptions where he was present. For the first time in his academic career, he found his path blocked by overt racism. “At Harvard, Locke had been a favorite son. At Oxford, he was a pariah,” Stewart writes. After Locke, it would be 56 years before another African American was awarded the Rhodes.

This hostile climate was part of the reason why Locke did not repeat his earlier academic successes at Oxford. Being separated by an ocean from his mother was another source of distress. In the end, he left Oxford without taking a degree—a fact he took care to conceal, partly because he did not want to disappoint the high expectations of those who had celebrated his achievement. (Later, he would return to Harvard and earn a doctorate.) Even so, the Oxford years were an important stage in his development. For one thing, he got his first taste of life in Europe, where he delighted equally in art treasures and in a freer sexual climate. For the rest of his life, he would spend as many of his summers as possible there.

Meanwhile, he found intellectual stimulation at Oxford’s Cosmopolitan Club, made up of students from British colonies in India and Africa. Here Locke was exposed to new ways of thinking about race and imperialism, which gave him a different perspective on his own black American experience. In a paper delivered at the club in 1908, he returned to the theme of his Dunbar lecture, emphasizing that true cosmopolitanism did not mean hovering above all local attachments, but in honoring particularity and difference. Better than an empty universalism, he wrote, “is an enforced respect and interest for one’s own tradition, and a more or less accurate appreciation of its contrast values with other traditions.” Locke was now prepared “to choose deliberately what I was born, but what the tyranny of circumstances prevents many of my folk from ever viewing as the privilege and opportunity of being an Afro-American.”

Once he returned to the United States in 1910, Locke began to forge the connections that would put him at the center of black intellectual life for the next five decades. He signed on to accompany Booker T. Washington on a fundraising tour of the South—his first time below the Mason-Dixon line, where he got a close-up view of Jim Crow. In Jacksonville, Florida, Washington delivered a speech while a riot was in progress, and his whole party had to be escorted by the police. It was a striking contrast with Europe, and left Locke permanently averse to living in the Deep South.

Thanks to Washington’s influence, Locke got his first job, as an assistant professor at Howard University. But while he would spend the rest of his career at Howard, Stewart shows that Locke was always looking for ways to break away from it. He felt stifled, sexually and intellectually, among Washington, D.C.’s, black bourgeoisie. He longed to be on the scene in New York, where in the 1920s an explosion of creativity was under way. Locke began to contribute essays on literature and the arts to Opportunity, the new literary magazine that was closely associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Here he could encourage young poets like Langston Hughes, and call attention to the triumphs of performers like Paul Robeson and Roland Hayes. He became particularly interested in African sculpture, seeing it as a resource for African-American artists. “Nothing is more galvanizing than the sense of a cultural past,” he wrote, in what could have been his critical credo. Like his Harvard contemporary T.S. Eliot, Locke was a believer in the close relationship between tradition and the individual talent.

Before long, he emerged as a trusted guide for white patrons and institutions looking to support black culture. As Stewart shows, this was often an uncomfortable position, since it meant negotiating the egos and agendas of donors: Albert Barnes, creator of the Barnes Foundation in Philadelphia and an early collector of African art, took umbrage when Locke broke with his favored artistic theories. Later there was Charlotte Mason, who supported writers like Hughes and Hurston but insisted that they call her “godmother.” And when Locke put together the Bronze Booklets, a pioneering series of short books by leading black scholars, he dropped the contribution by fellow Harvardian W.E.B. Du Bois for fear Du Bois’s radicalism would offend the foundation sponsoring the project.

Inevitably, Locke’s prominence and influence meant that he attracted critics. In particular, some objected to the way that his New Negro idea emphasized art and culture, rather than politics and economics, as the most important arena for black struggle. Du Bois threw down the gauntlet in his 1926 essay “Criteria of Negro Art,” where he famously proclaimed, “all Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists. I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda.”

It was in response to such attacks that Locke insisted on the “ethics of beauty itself.” Ever since his Harvard days, he had believed that the creation of art was a political act. And this is what makes him a thinker for our own times, when politics has once again assumed an urgency that might seem to make aesthetics a mere luxury. Literature and painting and drama, Locke believed, were the ways a people comes to consciousness; and that consciousness, once aroused, will inevitably have political consequences. “I believe we are at that interesting moment when the prophet becomes the poet,” he wrote in 1928. Such moments don’t come often, but when they do, they need critics and activists like Locke to interpret them. As Jeffrey Stewart writes at the end of The New Negro, Locke believed that “a spirit lurks in the shadows of America that, if summoned, can launch a renaissance of our shared humanity. That is his most profound gift to us.”