The sun shone brightly on Harvard and Lawrence S. Bacow on Friday, October 5, as Harvard inaugurated its twenty-ninth president. He will need to tap that solar energy, and other sources, like the support from an appreciative Tercentenary Theatre crowd, to tackle the fundamental issue he summarized in a succinct sentence early in his 3,600-word, 34-minute address: “These are challenging times for higher education in America.”

Elaborating the notes he sounded on February 11, when his appointment was announced, Bacow said:

For the first time in my lifetime, people are actually questioning the value of sending a child to college.

For the first time in my lifetime, people are asking whether or not colleges and universities are worthy of public support.

For the first time in my lifetime, people are expressing doubts about whether colleges and universities are even good for the nation.

Answering the question, “What does higher education really contribute to our national life?” he asserted, “We need, together, to reaffirm that higher education is a public good worthy of support—and beyond that, a pillar of our democracy, that if dislodged, will change the United States into something fundamentally bleaker and smaller.” (The text of his address begins below.)

After making the case that higher education’s becoming progressively available to more of the citizenry “has not only supported our democracy, but in some sense it has created it—and we are nowhere near done,” Bacow probed “the goodness of Harvard—and all of our universities” by examining their essential values: truth, or veritas; excellence; and opportunity. Crucially, he stressed the point of doing so together: not only stating higher education’s case to a doubting public, but also calling on academia to ensure that it is true to its values.

Thus, universities must embrace “both reassuring truths and unsettling truths,” which arise from those “who challenge our thinking.” Harvard must model the behavior it hopes to see elsewhere, “For if we can’t talk about the issues that divide us here, on this extraordinarily beautiful campus—where everyone is smart and engaged—where the freedom to speak one’s mind is one of our defining precepts—where we are blessed with abundant resources and no one goes to sleep in fear for his or her life—there is no hope for the rest of the world.”

“Our commitment to excellence,” he continued later, “should never be interpreted as an embrace of elitism. The excellence we represent is not a birthright. It is not something inherited by those born privileged—or even by those born with great aptitude. It is defined by more than numbers, and it encompasses spark and imagination, grit and determination.” Accordingly, “We need to remind the nation of the degree to which America’s greatness depends upon this commitment to excellence—and the fact that supporting excellence at college and university campuses does not run counter to the best interests of those who feel left behind by our society.”

As for opportunity, this son of refugees was moving and eloquent on the need to welcome and nurture people of talent: “It’s certainly one measure of a just society, how well we treat the least powerful among us. But beyond goodness, we must make the case for common sense: that failing to welcome talented students and scholars from around the world is to undercut America’s intellectual and economic leadership.”

In her inaugural address in 2007—it seems a different era now—historian Drew Faust emphasized universities’ obligations to the past (culture, the arts, their collections) and the future (research, innovation, and teaching), more than to the present. For Lawrence S. Bacow—social scientist, lawyer, seasoned academic leader—the focus is, necessarily, on higher education’s present: full of opportunities for discoveries and progress, but also full of very present dangers.

Crimson Celebrations

If Bacow’s remarks looked principally outward (the single campus initiative he detailed was a commitment to raise funds for public-service internships for all interested undergraduates), the inauguration was thoroughly Harvardian.

Thursday night, in Sanders Theatre, the “Musical Prelude to the Inauguration: A Welcome and Celebration,” crafted by the Office for the Arts, showcased students and teachers making and performing multiple arts at the University. In the wake of the Faust administration’s arts initiative, there are more practitioners on the faculty, teaching a broader range of performers—including the undergraduates newly concentrating in theater, dance, and media.

The talents on display ranged from pianist Tony Yang ’21 and Carissa Chen ’21 performing a “duet” of sorts (she painting a large canvas while he played Debussy’s “Clair de lune”) to a cutting-edge, Asian-fusion-jazz quartet: Rosenblatt professor of the arts and jazz pianist Vijay Iyer; senior lecturer on music and director of jazz bands Yosvany Terry; and graduate students Rajna Swaminathan, a percussionist and composer, and Ganavya Doraiswamy, a vocalist. Tradition was served when three undergraduate a cappella groups—the Krokodiloes, the Harvard Opportunes, and the Radcliffe Pitches—singly and together performed a medley of modified Motown hits (sample lyric: “He’s leaving on that midnight T to Harvard”), an affectionate nod to Bacow’s Michigan roots.

Lawrence Bacow and Adele Fleet Bacow, exhilarated and clearly moved, came to the stage to applaud the performers. She thanked the artists for their indelible demonstration of “the passion, the soul of Harvard.” He extended the thank-you to the people backstage who had made the performance possible.

The Bacows were very much on duty the next morning, as visiting dignitaries and friends of Harvard present for the occasion were served a continental breakfast-cum-edification at “A Taste of Harvard,” under the tent on the Science Center Plaza: fuel plus exhibitions on projects, programs, and partnerships from across the University, including the student-run Crimson EMS, the research assets of the Harvard Forest, Harvard Law School’s Veterans Legal Clinic, and more. As is their wont (as the community is coming to understand), the couple appeared to visit each exhibit, greet guests for casual conversation, and generally enjoy themselves on an increasingly brilliant morning.

This was only the latest demonstration of their personal engagement with seemingly everyone on campus (a hallmark of their presence during his Tufts presidency)—establishing relationships and promoting messages about the University’s opportunities. President Bacow welcomed the inaugural cohort of participants in the new First-Year Retreat and Experience pre-orientation, for first-generation, low-income, and other students from underrepresented backgrounds. The couple donned Move-In T-shirts to greet students and their parents—and even helped schlep stuff from cars to dorm rooms on a hot August morning. In mid September, they traveled to his boyhood home, in Pontiac, and to Detroit, where he unveiled research partnerships with the University of Michigan to address urban poverty and the opioid crisis: templates for extending Harvard’s reach and impact. And speaking to faculty members at a teaching symposium a week later, he put their work on campus in a broader context, as well, asking, “How can we ensure that what we are doing here benefits all the students who are trying to learn in America?”

At its core, of course, Harvard is committed to research and teaching. After the inauguration breakfast, eight simultaneous symposiums showcased aspects of faculty scholarship, from behavioral economics, data science, and genomics to such policy challenges as delivering effective early-childhood education and addressing inequality.

Inaugurating the President

The afternoon began with the academic procession into Tercentenary Theatre at 2:06 p.m., led by Reserve Officer Training Corps candidates and the University Band. Among those filing in was a group signed “academic advisers”: Bacow’s Harvard doctoral mentors, still active members of the faculty, whom he recognized and thanked in his remarks later.

The Inauguration Theme and Fanfare, performed by the Harvard-Radcliffe Orchestra, is home-grown: a composition by Williams professor of urban planning and design Jerold Kayden ’75, J.D. ’79, a trumpeter and HRO president in college.

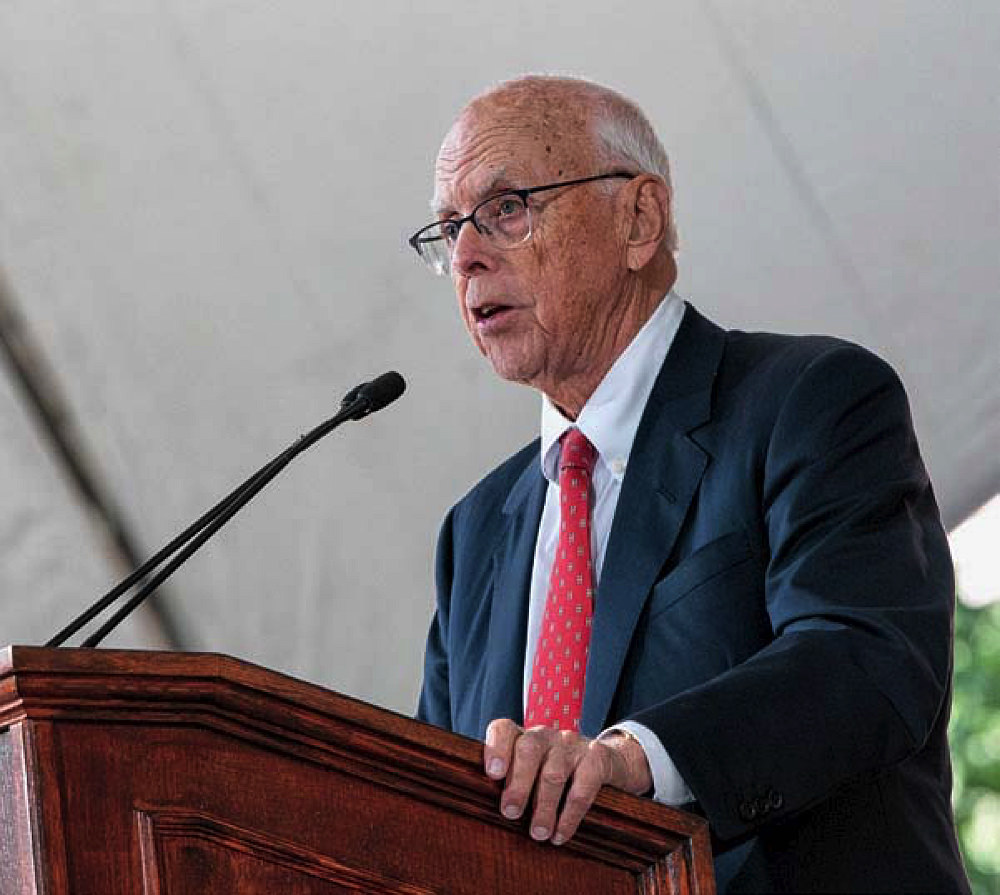

M.C. John P. Reardon Jr. ’60

Photograph by Jim Harrison

In selecting John P. Reardon Jr. ’60 to serve as master of ceremonies, beginning with the call to order, Bacow settled on the living embodiment of the University’s last half-century: associate dean of admissions and financial aid, director of athletics, executive director of the Harvard Alumni Association, adviser to the president and the Governing Boards, and Harvard Medalist—the consummate Harvard people-person. Reveling in the occasion, Reardon proclaimed, “What a beautiful day for this great inauguration.”

The choice of “America the Beautiful” as the initial anthem reflects the aspirational nature of the lyrics, according to Andrew G. Clark, director of choral activities and senior lecturer on music. As such, it ties to Bacow’s personal narrative as the son of refugees who fled Europe for the United States, to make new lives. Having Cambridge seventh-grader Alan Chen as lead soloist made it explicitly intergenerational, and underscored Harvard’s ties to its home community. (The day had personal connections for Clark, too: he had the same duties at Tufts from 2003 to 2010, before coming to Harvard, and knew the Bacows as “wonderful supporters of the arts and of students’ work.”)

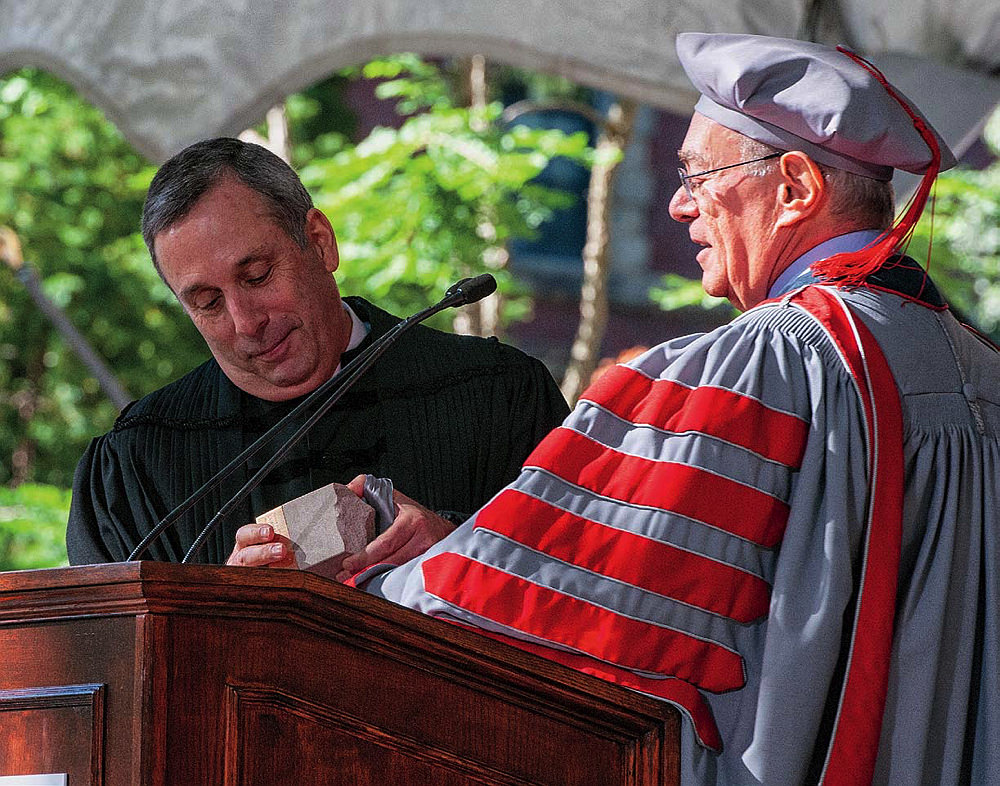

MIT president L. Rafael Reif salutes "favorite son" Larry Bacow (MIT ’72) with a (meaningful) gag gift

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Among the speakers, L. Rafael Reif, president of MIT (Bacow’s undergraduate alma mater, and then, following his Harvard degrees, his academic home for 24 years), especially wowed the crowd, toasting MIT’s “favorite son” whom he had come “to drop…off at college.” He even insinuated that getting Bacow installed in Mass Hall ranked among the best of MIT’s famous hacks, and concluded by presenting a reminder of “home”: a piece of limestone from the original MIT Dome, inscribed,

Lawrence S. Bacow, MIT Class of ’72.

The 29th president of Harvard and a chip off the old block!

Catherine L. Zhang

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Succeeding speakers represented the faculty (Robin E. Kelsey, Burden professor of photography), students (Catherine L. Zhang ’19, president of the Undergraduate Council), the Harvard Alumni Association (president Margaret M. Wang ’09), and members of the University staff (Calixto Sáenz, director of the microfluidics microfabrication core facility at Harvard Medical School—a first-generation immigrant from Colombia, lifted up by higher education: a life story resonant with Bacow’s). [Read a full account of these and other speakers’ remarks, and the inaugural proceedings, here.]

Calixto Sáenz

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Then came the official inauguration, begun by the president of the Board of Overseers, Susan L. Carney ’73, J.D. ’77—U.S. Circuit Judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals, Second Circuit—who cited Bacow’s “instinct for collaboration and thirst for innovation,” among other strengths, as the experienced helmsman sets “sail for the adventures ahead.”

Harvard’s four living presidents emeriti—Derek C. Bok, J.D. ’54, LL.D. ’92; Neil L. Rudenstine, Ph.D. ’64, LL.D. ’02; Lawrence H. Summers, Ph.D. ’82, LL.D. ’07; and Drew Gilpin Faust—were on hand to invest Bacow with four symbols of his new office. Bok conveyed the large keys, from 1846; Rudenstine, the oldest College Book, containing records dating back to 1639; and Summers and Faust, the Harvard seals.

The Corporation’s Senior Fellow, William F. Lee ’72, concluded the formalities by conveying the final symbol of office, the Harvard Charter of 1650. Before doing so, Lee said those attending had “come together to celebrate a new presidency, but far more, we celebrate an idea”—that higher education is a force for good, for understanding and discovery that “serves the world.” Higher education had been Bacow’s guiding star throughout his life, Lee said, and he hoped that all present would follow that star, too, advancing Harvard, the community, and the world. After Lee and Bacow displayed the charter, Lee led him to the president’s ceremonial, and famously uncomfortable, chair—and in his first decisive act after being inaugurated, Bacow followed Lee’s advice not to sit in it for long.

After the president’s address, the Bacows’ rabbi and close friend, Wesley Gardenswartz ’83, J.D. ’86, senior rabbi of Temple Emanuel in Newton Center, offered an intensely personal, emotional benediction and blessings. Thereafter, the Inauguration Choir returned to sing the Hebrew conclusion to Chichester Psalms, composed by Leonard Bernstein (more Harvard: ’39, D.Mus. ’67), whose centennial is being celebrated this year.

Then came the singing of “Fair Harvard,” spruced up with its newly inclusive last line. The last notes of the recessional having wafted skyward, and the bells having boomed out their notes at 4:25, it was off to the “Bacow Block Party” in the Old Yard—there to be fed and entertained.

A short distance away from the hubbub, the sugar maples at Loeb House—where the Governing Boards do their work, and where Lawrence S. Bacow had begun his presidency in July—were in splendid autumn color. Definitively, the seasons had turned—and even more definitively, a new Crimson team’s new season was well begun.

The Inaugural Address

“Challenging Times for Higher Education”

This truly is an astonishing sight, seeing so many of you here in Harvard Yard today.

It’s a great reminder that nobody gets anywhere of consequence in this world on his or her own—and that includes becoming president of Harvard.

I have been blessed to have people ready to help me at every step of the way, beginning with my parents, who worked hard every day to ensure that I had boundless opportunities. I would not be here today without the love of my life, Adele, who has made my life so meaningful and rich, and also without my children, from whom I have learned and continue to learn so much.

I thank all of my family and my dear friends, who are also family, for traveling from far and wide to be here.

I have been blessed, also, by inspiring teachers and mentors, three of whom I am honored to have with me today—my Harvard dissertation advisors, Mark Moore, Richard Zeckhauser, and Richard Light—to mark it. Thank you for having taught me so well.

I would also like to thank my predecessors Drew Faust, Larry Summers, Neil Rudenstine, and Derek Bok for their thoughtful stewardship and leadership of Harvard over the last half-century.

Five living presidents, from left: the emeriti Lawrence H. Summers, Drew Gilpin Faust, Neil L. Rudenstine, and Derek C. Bok—with successor Larry 29

Photograph by Jim Harrison

I would also like to thank each of them for their excellent advice as I take the helm.

A special thanks also to my colleagues from Tufts and from MIT, who taught me how to be a leader in higher education. I guarantee you that there are many people assembled here who pray that you taught me very well!

Of course, the Harvard presidency seems to involve some unique hazards—and over its long history, a nearly infinite list of potential missteps.

President Langdon, for example, was forced to resign after the students found that his sermons dragged on too long—a great incentive for me to be brief today.

President Mather, on the other hand, outraged the entire Harvard community by refusing to move here from Boston, arguing that the air in Cambridge did not agree with him. Fortunately, I actually like the atmosphere here a lot!

Even President Eliot, arguably Harvard’s most successful president, provoked an uproar now and then. He wanted to abolish hockey, basketball, and football, on the grounds that they required teamwork, and, in his mind, Harvard had absolutely no use for that. He also tried over and over again to acquire MIT.

Rafael, you can relax. I’ll do my best to avoid all such misadventures.

I am deeply honored to assume the leadership of this wonderful institution, and proud that as the nation’s oldest university, Harvard has helped to shape the American system of higher education, which is magnificent in its independence, sweep, and diversity.

I am also honored that so many other great institutions are represented here today, and I thank all of my colleagues from all over the country and all over the world for your good wishes—and, frankly, your support, because this is not an easy moment to assume the leadership of any college or university.

These are challenging times for higher education in America.

For the first time in my lifetime, people are actually questioning the value of sending a child to college.

For the first time in my lifetime, people are asking whether or not colleges and universities are worthy of public support.

For the first time in my lifetime, people are expressing doubts about whether colleges and universities are even good for the nation.

These questions force us to ask: What does higher education really contribute to the national life?

Unfortunately, more people than we would like to admit believe that universities are not nearly as open to ideas from across the political spectrum as we should be; that we are becoming unaffordable and inaccessible, out of touch with the rest of America; and that we care more about making our institutions great, than about making the world better.

While there may be—may be—a kernel of truth here, if I believed that these criticisms fundamentally represented who we are, I would not be standing before you today. All of our institutions are striving to make wise choices amidst swirling economic, social, and political currents that often make wisdom difficult to perceive.

We need, together, to reaffirm that higher education is a public good worthy of support—and beyond that, a pillar of our democracy that, if dislodged, will change the United States into something fundamentally bleaker and smaller.

It’s worth remembering that most of the nation’s founders were first-generation college students. They not only shaped our form of government, they built new universities. Having had their own minds opened and improved by learning, they were certain that government by and for the people requires an educated citizenry.

Even at some of the most difficult moments in our national history, our leaders understood that they could strengthen the nation by educating more of our society. Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act during the dark days of the Civil War, creating land-grant universities to spread useful knowledge across this immense raw continent.

President Franklin Roosevelt signed the G.I. Bill just two weeks after D-Day, making a college education one of the prime rewards for national service, and sending vast numbers of less-privileged Americans to college for the first time.

Every such expansion of higher education, every move toward openness to those previously excluded, has brought the United States closer to the ideal of equality and opportunity for all.

So higher education has not only supported our democracy, but in some sense it has created it—and we are nowhere near done.

My friend Drew Faust has often wished for Harvard that it be as good as it is great. To me, the goodness of Harvard—and of all of our universities—lies in the three essential values we represent: truth, or, as we say here, veritas; excellence; and opportunity.

Today, we have to embody and defend truth, excellence, and opportunity more than ever. We do this not to stave off our critics, but because these are the values that made our nation great.

As we consider truth, clearly, we’ve come a long way from the days when our colleague United States Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.”

Now that technology has disintermediated the editorial function, allowing anybody to publish his or her own view of events, our fragmented media struggle to make the distinction between opinion and facts. The result, often, is a feverish diffusion of rumor, fantasy, and emotion unconstrained by reason or reality.

And it is precisely because we find ourselves in this post-factual world that strong colleges and universities are essential.

Given the necessity today of thinking critically and differentiating the signal from the noise, a broad liberal arts education has never been more important. It is our responsibility to educate students to be discerning consumers of news and arguments, and to become sources of truth and wisdom themselves.

Of course, facts and truth are not the same. Facts are incontrovertible, or at least they should be, whereas truth has to be discovered, revealed through argument and experiment, tested on the anvil of opposing explanations and ideas. This is precisely the function of a great university, where scholars debate and marshal evidence in support of their theories, as they strive to understand and explain our world.

This search for truth has always required courage, both in the sciences, where those who seek to shift paradigms have often initially met with ridicule, banishment, and worse, and in the social sciences, arts, and humanities, where scholars have often had to defend their ideas from political attacks on all sides.

There are both reassuring truths and unsettling truths, and great universities must embrace them both. Throughout human history, the people who have done the most to change the world have been the ones who overturned conventional wisdom, so we should not be afraid to welcome into our communities those who challenge our thinking.

In other words, our search for truth must be inextricably bound up with a commitment to freedom of speech and expression.

At Harvard, our alumni span the political and philosophical spectrum, including those who have served in the White House, in Congress, on the Supreme Court, and in comparable positions throughout the world. Here in Harvard Yard, we must embrace diversity in every possible dimension, because as Governor Baker said so eloquently, we learn from our differences—and that includes ideological diversity.

As faculty, it is up to us to challenge our students by offering them a steady diet of new ideas to expand their own thinking—and by helping them to appreciate that they can gain much from listening to others, especially those with whom they disagree. We need to teach them to be quick to understand, and slow to judge.

Let me say that again: We need to teach our students to be quick to understand, and slow to judge. And as faculty, we owe this duty to each other, as well.

To paraphrase the great theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, it is always wise to look for the truth in our opponents’ error, and the error in our own truth.

At Harvard, we must strive to model the behavior we would hope to see elsewhere. For if we can’t talk about the issues that divide us here, on this extraordinarily beautiful campus, where everyone is smart and engaged, where the freedom to speak one’s mind is one of our defining precepts, where we are blessed with abundant resources and no one goes to sleep in fear for his or her life — if we can’t do that here, there is no hope for the rest of the world.

At the same time, we should not apologize for standing for excellence in everything we do.

Harvard is synonymous with excellence.

We scour the world for students and faculty prepared to demonstrate brilliance in our classrooms, our laboratories, on our playing fields and performance stages, and out in the community striving to make a difference.

Our commitment to excellence should never be interpreted as an embrace of elitism. The excellence we represent is not a birthright. It is not something inherited by those born privileged—or even by those born with great aptitude. It is defined by more than numbers, and it encompasses spark and imagination, grit and determination.

The excellence we stand for is only achieved through tireless pursuit. Scholarship is about charging down dark alleys, accepting disappointment, and setting off again. It is messy and laborious by definition. Much as we love to celebrate the “Eureka!” moments in our society, they are generally preceded by years of early mornings and late nights.

We need to remind the nation of the degree to which America’s greatness depends upon this commitment to excellence—and the fact that supporting excellence at college and university campuses does not run counter to the best interests of those who feel left behind by our society.

Indeed, it is scholars here and elsewhere who have sounded the alarm about increasing income inequality and declining social mobility in the United States, and whose ideas will help us become the just society we hope to be.

The research we pursue in all fields helps to generate new knowledge, new connections, and new insights into the human condition. We work to understand the origins of life, but also the meaning of life. We explore the molecular code that makes us human, and the culture that is equally essential to our humanity.

Long after the technologies of today are obsolete, people will still be reading Shakespeare and Gabriel García Márquez; listening to Mozart, Bob Dylan, and the late, great Aretha Franklin from my hometown of Detroit; and contemplating the great questions that have motivated philosophers and poets for millennia. For it is our art, our literature, our music, and our architecture which are among the most enduring artifacts of human endeavor. As the nation’s oldest institution of higher learning, Harvard has a special responsibility to champion intellectual traditions that have defined educated men and women since the dawn of civilization.

We do more than deliver a body of knowledge to our students—we expand their humanity. By teaching young people to appreciate what is beautiful in art, society, and nature, we help them to discover what makes life truly worth living.

Of course, none of our institutions can afford to be complacent about our excellence. We have competitors around the world, supported by governments that understand that the swiftest route to a thriving economy runs through university laboratories, libraries, and classrooms.

Whether our colleges and universities are public or private, we all rely upon the generosity of the American people, who contribute both to research and financial aid. We are excellent because of them, and must endeavor to deserve their support. So it’s up to us to remember, always, our collective obligation to the public good.

Since Harvard’s founding in 1636, the people educated here have responded patriotically to the call to service. With the exception of the service academies, more Harvard alumni have received the Congressional Medal of Honor than any other school. Harvard people have always vigorously engaged in the great issues of their day, and at this very moment 68 of our alumni are running for Congress, on both sides of the aisle. And our alumni throughout the world are working to strengthen their nations.

We need to ensure that future generations continue to serve the greater good in a variety of ways. It is my hope that every Harvard graduate, in every profession, should be an active, enlightened, and engaged citizen. So I am pleased to announce today we will work toward raising the resources so we can guarantee every undergraduate who wants one a public-service internship of some kind—an opportunity to see the world more expansively, and to discover their own powers to repair that world.

Of course, we cannot achieve excellence if we are only drawing talent from a small portion of society, so our colleges and universities also must stand for opportunity.

In the broadest sense, all of us are indeed created equal: Talent is flatly distributed. But sadly, opportunity is not.

Throughout our history, higher education has enabled the most ambitious among us to rise economically and socially. And every step the nation has taken to print more such tickets into the middle class, and beyond, has powered our economic growth and leadership in innovation.

We have to ensure that higher education remains the same economic stepping-stone for those from modest backgrounds that it was for my generation and my parents’ generation. While a college education still helps to level the playing field for those who manage to graduate, the cost of entry, and of staying the course until graduation, has become daunting for many families.

This is why Harvard’s groundbreaking Financial Aid Initiative, started by Larry Summers and expanded by Drew Faust, is so important. We simply say to low- and middle-income families with earnings below a certain level, “You can send your child to Harvard and we will ask you to pay nothing.” Largely because of this, 268 members of this year’s first-year class are the first in their family to attend college.

Clearly, however, Harvard cannot keep the American Dream alive single-handedly.

Our nation’s magnificent public colleges and universities, where four out of five American students are educated, are key. But state appropriations are funding a diminishing share of the cost of that education, so tuition and student debt are rising. This trend is not sustainable.

In failing to adequately support public higher education, we are literally mortgaging our own future. At a time when other countries are investing more in support of higher education, we as a nation cannot afford to invest less.

As higher education leaders, we also need to do what we can do to bend the cost curve. Higher education is one of the few industries where competition tends to drive costs up. It’s time to stop this arms race, and to consider the benefits of greater cooperation.

These can include shared infrastructure for research, joint graduate student and faculty housing, or exchanges that allow us to eliminate some of the redundancies in our curricula and to double down on our specific strengths. I look forward to working with my colleagues at Boston-area institutions to explore how we can collectively do a better job of serving both our students and society.

We also have to explore the opportunities offered by technology to improve productivity and access. I am proud that Harvard, in partnership with our colleagues at MIT, has been a leader in opening up educational opportunities to talented students throughout the world through edX. In turn, they have us offered new insights into the science of learning.

As college and university presidents, we also need to be much franker in framing the choices our institutions make, so as to reveal their true consequences in terms of cost. Traditionally, colleges and universities have been great at doing more with more. But in the future, we may have to do more with less.

At the same time, it’s our responsibility to counter any current myths about the value of higher education and to continue telling children, in every corner of this nation and the world, the simple truth: that if they want to get ahead, education is the vehicle that will bring them there.

College has enabled the American Dream for so many of us—and we must nurture and sustain that dream for generations to come.

My parents came to this country with virtually nothing. My father arrived here as a child, a refugee escaping the pogroms of Eastern Europe. My mother survived Auschwitz as a teenager, lived without bitterness, and always was grateful that America was so good to her.

This is a common story—this is America’s story. With the exception of Native Americans and the descendants of those enslaved or brought here against their will, most of us can trace our origins back to people who, like my parents, came to these shores seeking freedom and opportunity, and a better life for their children. And many continue to make this journey today, despite enormous risks.

It certainly is one measure of a just society how well we treat the least powerful among us. But beyond goodness, we must make the case for common sense: that failing to welcome talented students and scholars from around the world is to undercut America’s intellectual and economic leadership.

In this global economy, financial capital moves at the speed of light, and natural resources also move swiftly. The only truly scarce capital is human and intellectual capital. That is what a nation must aggregate and nurture, if it intends to be prosperous.

Fortunately, many of the best and the brightest from around the world seek to study at America’s great colleges and universities. In engineering, mathematics, and computer sciences, over half the doctorates awarded each year are granted to foreign nationals. Many of these students will return home with their sights raised, and go on to build thriving companies and institutions of higher learning; to fight poverty, disease, and climate change throughout the world; and to lead their own nations toward goodness and greatness.

But a considerable number of these international students will do everything possible to stay right here. Rather than turn them away, we should embrace these extraordinary people. Over a third of our faculty were born someplace else. Over a third of the Nobel Prizes awarded to Americans in chemistry, medicine, and physics since 2000 have gone to men and women who were foreign-born. Over 40 percent of Fortune 500 companies were founded by immigrants or their children.

America has to continue welcoming those who seek freedom and opportunity, lest we shut the door to the next generation of great entrepreneurs, scholars, public leaders—and, dare I say, university presidents—for it is immigrants that get things done, as Lin-Manuel Miranda said so well in “Hamilton.”

I hope that all of us in higher education remain true to our essential values—to truth, excellence, and opportunity. But I hope, as well, that in remaining true to them, we advance those values in the world at large.

It’s not enough that we represent the very best of society, in terms of intellectual achievement, freedom to express and explore, and openness to extraordinary potential in all who possess it.

We must defend the essential role of higher education in the life of our nation and the broader world.

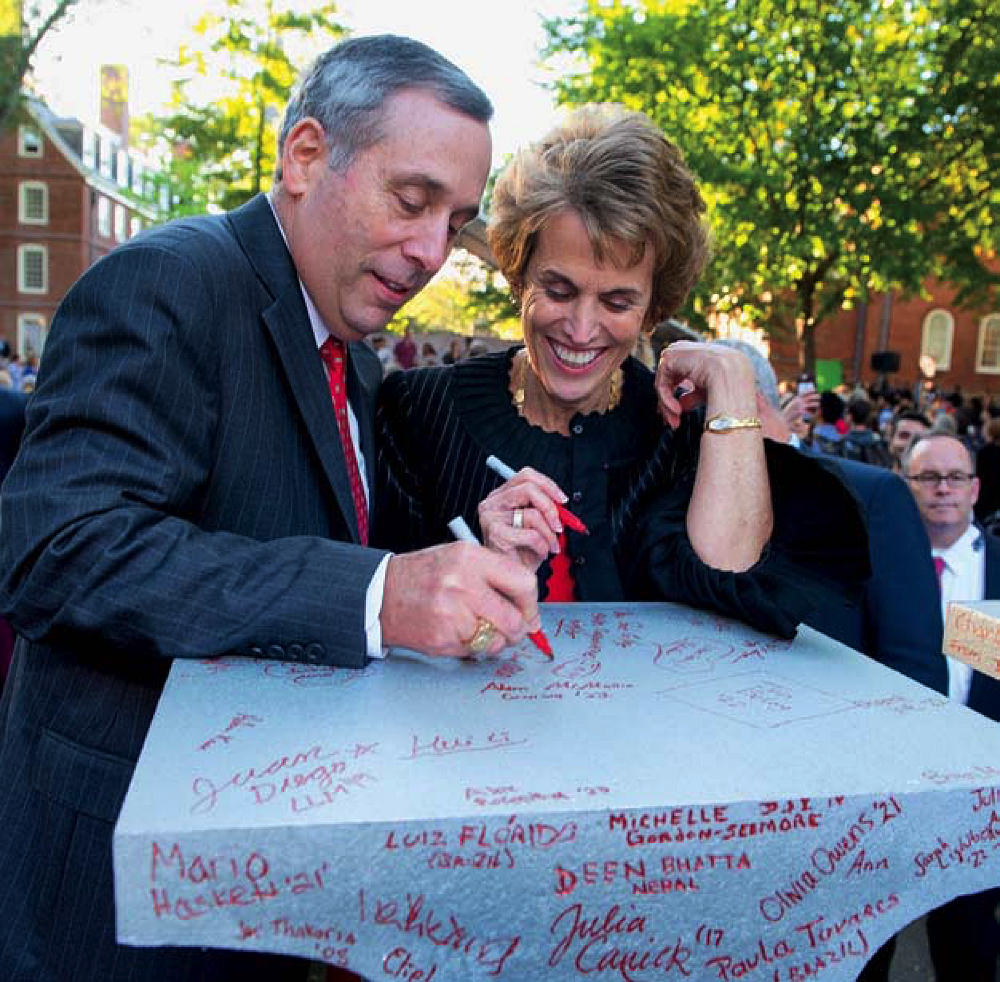

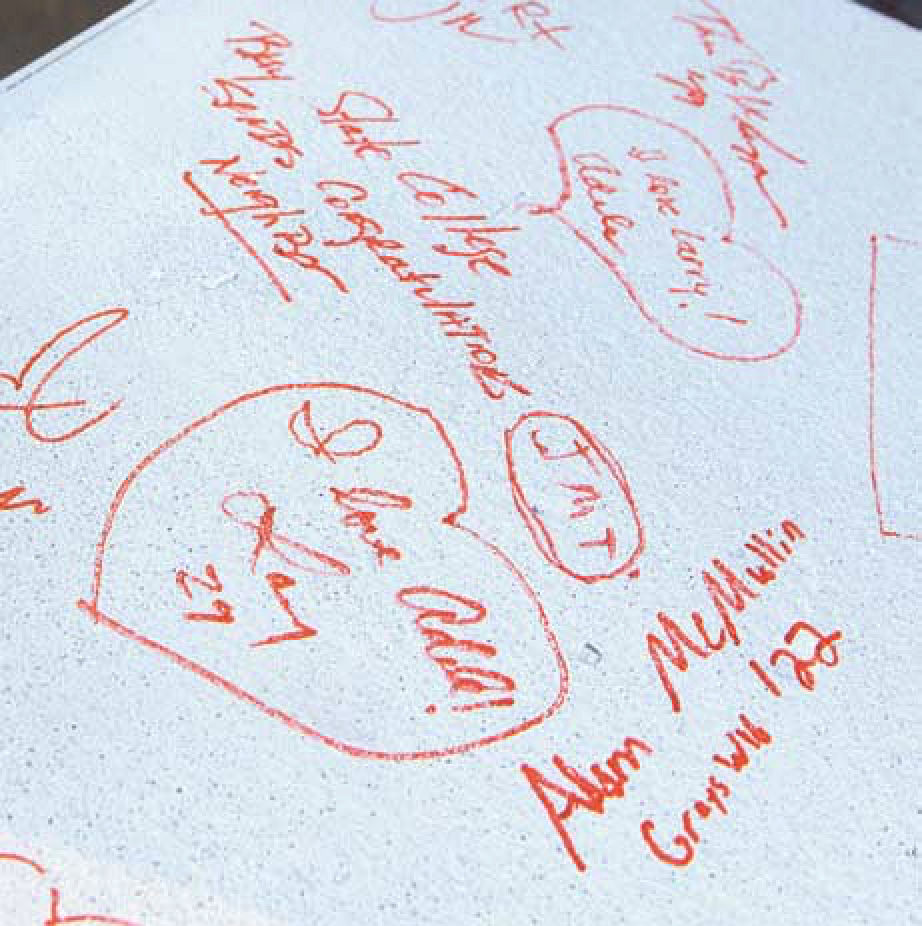

Sharpie time

Photograph by Jim Harrison

And we must reach outwards even beyond that.

We have a responsibility—we have a responsibility—to use the immense resources entrusted to us—our assets, ideas, and people—to address difficult problems and painful divisions.

We have a responsibility, as well, to help America remember its own essential goodness: the kindness, decency, and integrity of our founding principles, as well as the kindness, decency, and integrity of those people who have fought throughout our history to ensure that these principles apply equally to all.

The president, inaugurated, makes his mark: Larry 29.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

It is up to us to leave our country and our world a better place tomorrow than it is today.

That is where true greatness lies.

I am honored to be able to work alongside each and every one of you to reach such greatness.

I am thankful for this opportunity to lead Harvard, which made me better, and which I think makes everyone better—spurring all of us to summit mountains we never imagined we could climb.

Today, I am inspired by the beauty of our mission, our history, and our values, by the power of our ambition, talent, and goodwill, and by the infinite possibilities before us, to use our strengths to help humanity as a whole to ascend.

It is a very great privilege to seize those possibilities with you, and I am delighted to begin.

Thank you.