Dick Friedman ’73—proud alumnus of both Fair Harvard and Sports Illustrated, where he toiled for many years—covers contemporary Crimson football for this magazine each fall, in lively, nuanced accounts resonant with the sport’s history. Now he has dived deep into the glory days, a century and more ago, when big-time college football meant Harvard vs. Yale. In this excerpt from chapter eight of his new book, The Coach Who Strangled the Bulldog: How Harvard’s Percy Haughton Beat Yale and Reinvented Football, Friedman recalls the now unlikely-seeming origins of the industrial-strength “amateur” contests currently featured on campuses across the land (and national television broadcasts) each autumn and early winter.

~The Editors

Spanning the Charles River from Boylston [now Kennedy] Street to the entrance of Soldiers Field, the Larz Anderson Bridge opened in time for the 1913 season. Supplanting a narrow, rickety, wooden drawbridge that had been a choked, dust-kicking trial on game days, the sturdy, paved structure made the march from Harvard Square to the stadium more tolerable, especially for the multitudes who trekked across and back for the big games and championship games. Its very solidity and permanence also symbolized that the relationship—perhaps unholy—between colleges and sports was now set in stone.

Beginning as early as the 1880s, Harvard, Princeton, and Yale had decided that it was part of their mission, educational or not, to provide sporting entertainment for the masses. In the 1890s, Harvard president Charles W. Eliot decreed that his school would no longer play major football games at neutral sites, but on campus only. Within 20 years the Big Three all would have colossal stadiums, and game day had become a ritual, complete with spectacle, song, and spirit. For good or for ill, these institutions set the pattern that has been followed and refined by universities to this day.

There were many carpers, at Harvard and elsewhere. Muckraker Henry Beach Needham, in his 1905 McClure’s exposé, had put his finger on the win-at-all-costs mentality and the creeping realization that the cart was pulling the horse: “The physical development of the student body is neglected, that eleven men of the university may perform for the benefit of the public.” The disdain for the immersion into the muck of so-called big-time college sport drips from the comments of the eminent historian Samuel Eliot Morison, A.B. 1908, Ph.D. ’12, Litt.D. ’36, in Three Centuries of Harvard, his official history published for the University’s tricentennial in 1936. These included a swipe at another son of Harvard, Percy Duncan Haughton, A.B. 1899. “Haughton was the first of the modern ‘big-time coaches,’ and he certainly ‘delivered the goods,’” sniffs Morison, “but it may be questioned whether his talent for picturesque profanity made the game more enjoyable, or whether his strategical and tactical developments turned football in the right direction.” Give the man his “H”—for Harrumph!

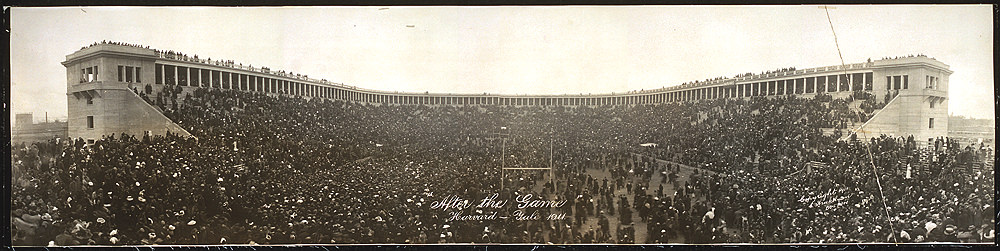

After The Game in 1911

Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress

Morison did concede a positive aspect: “The growth of athletics tended to integrate college life in the [Charles W.] Eliot era; participation in them, both as players and as managers, brought together men of the widest social origins, and victory over Yale in the four ‘major’ sports of football, baseball, rowing and track was something that the entire College prayed for.”

Those who deplored what football had wrought were bowled over like a would-be tackler in the way of Haughton’s gang of interferers. The athletic horse had left the athletic barn; though it would be reined in some after World War II, the rest of America took note, especially of the financial windfalls a mighty team could generate. The school had become dependent on ever-burgeoning football receipts to fund its entire athletic program. In 1917, receipts for all of the school’s athletic events would be $155,608.72, with football delivering all but $12,461.53 of that total. (Football netted $106,688.34 that year, the athletic program as a whole only $38,302.64.) Thus football was funneling more than six figures in profit to the athletic association, keeping the rest of the department afloat.

Even amid unparalleled success on the field and at the gate, Harvard’s leaders—including those who championed the Crimson teams—acknowledged unease. Foremost was President A. Lawrence Lowell, Eliot’s successor, who accurately identified the emerging self-aggrandizing sports apparatuses. (Today the self-perpetuating athletic department expansion is labeled “the gold-plating of college sports.”) “The vast scale of the public games has brought its problems,” declared Lowell in his annual report for 1912. “They have long ceased to be an undergraduate diversion, managed entirely by the students, and maintained by their subscriptions. They have become great spectacles supported by the sale of tickets to thousands of people….Money comes easily and is easily spent under the spur of intense public interest in the result of the major contests, and a little laxity quickly leads to grave abuse.…Graduates, who form public opinion on these matters, must realize that intercollegiate victories are not the most important objects of college education. Nor must they forget the need of physical training for the mass of students by neglecting to encourage the efforts recently made to cultivate healthful sports among men who have no prospect of playing on the college teams.”

“Big-time” coach Percy Duncan Haughton

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

Many within the Harvard community complained that academically many of the star athletes were unworthy. These were not the functional illiterates who festoon too many college rosters today. The Crimson players had passed the entrance exam….most had, anyway. Many were admitted “with conditions.” But would they have been dozing through classes in Sever Hall if not for their ability to punt or carry a football?

The schizophrenia was illustrated by the Harvard Alumni Bulletin (today Harvard Magazine, where the author is a contributing editor). At the same time that it was breathlessly printing play-by-play of the football games (complete with photos and diagrams), the publicationalsomoralized. “Are our colleges and universities being injured or aided by the recruiting of boys who are brought to them because they are athletes…?” it editorialized in 1913. “We believe that this type of undergraduate…may be in every way a sound and wholesome person, and on the way to become a useful, and perhaps a leading, citizen; but if the college attracts him chiefly as an athletic club and a place to earn a sweater decorated with a precious letter, his path to usefulness should not lie through the college….The fact is that, driven on by the enterprise of our sporting editors, we are as a people losing our balance in the matter of athletics.”

Then as now, some were indignant about the “almost scandalous” amounts spent to equip footballers. Proclaimed the Bulletin in 1911—right after the Crimson had been declared national champion, and shortly after Dean LeBaron R. Briggs had issued a report criticizing the athletic department’s management—“Some months ago the Bulletin asked why it cost $1000 per man to put a football squad through a seven-weeks season when that amount is more than it takes to carry the average student through an entire year….Why should not the accounts of the athletic organizations be made public in detail?...We daresay there would no longer be large items of expenditure for ‘taxicabs as the sole means of getting about, and for costly dinners with wines and cigars.’”

Others were aghast at the coarsening of spirit engendered by the desperation to beat Yale. The keening and barking of the stadium crowds was perhaps fine for the working classes watching the Red Sox at Fenway Park but it was unworthy of Harvard men. After Harvard superstar Charlie Brickley ’15 dropkicked the Elis into submission in 1913, one correspondent, calling himself “Sporticus Antiquus,” was concerned about...the tone. “Whenever Harvard had the ball on the Yale side of the field during the recent game in the Stadium, the Yale crowd set up a great noise, in order to drown, if possible, the signals given to the Harvard men. So also, whenever Brickley prepared to make a drop or place kick, the Yale ‘rooters’ burst forth in shouts and cat-calls in their effort to ‘rattle’ him…. Not only Harvard men, but neutrals who belong to neither university, and a saving remnant of Yale men themselves, deprecate a practise which mars the pleasure of witnessing athletic contests.”

Well, then. Did this concern engender widespread guilt? If so, it was drowned out by the shouts of victory. Fred Moore, the Harvard Athletic Association graduate treasurer, summed up the prevailing sentiment. In his report for the fiscal year ending on July 31, 1915 (and thus encompassing the 1914 Yale game), Moore wrote: “When the score is 36 to 0, and the receipts from the game are $138,000.00, it is rather difficult for the manager to refuse the team and coaches anything in reason they may desire.”

The football-industrial complex had a multiplier effect. In 1916-17, expenses for training table were $2,424.30, for doctors $2,791.66, for “rubbing” (masseurs—we hope) $1,318.25, for travel $6,477.66. The coaching staff got $9,630.00. Expense of games came to $16,603.93, a figure swelled by “expense of large games” (some of which was shared by the visitors). Eight undergraduates were required to look after the business part of the enterprise—a manager (a post that could be lucrative through the sale of program ads and hence was much coveted), a first assistant manager, and six assistant managers.

The Boston Globe in 1911 noted, “There are little sidelights to a big football game that are interesting. There were 276 student ushers at the Carlisle game, and there will be 300 or more at the Dartmouth and Yale games. There are also required 100 or more policemen. Lunch is served for these 400 men at 12 o’clock in the baseball cage. The details of management of a big football game are certainly considerable.”

Most spectators traveled to the stadium on foot or by streetcar, but with such a well-heeled (and well-wheeled) clientele, parking on Soldiers Field also became a thriving enterprise. In 1913, for the early-season games, a parking (or “checking”) space cost 25 cents; for Brown and Yale, a half-dollar. And the economic effect extended well beyond the stadium. For those shut out of the arena, Boston music halls offered scoreboards, running play-by-play, and even live entertainment. For the weekends of major games, hotels were booked months in advance, and the music halls featured big-name stars.

The spectators were just as glittering. As The New York Times reported the day after the 1910 Game at Yale, “Special trains, private cars and automobiles began rolling into New Haven by 9 o’clock this morning, and the entry of fashionable folk from New York and Boston kept up a steady procession....There were thirty-five specials in all....” From Boston came Mayor John F. (Honey Fitz) Fitzgerald, among whose party was daughter Rose, who four autumns later would wed Joseph P. Kennedy, A.B. 1912.

Like other sports with mass appeal, such as baseball, horse racing, and boxing, football was producing its mandarin class of scribes. For the “championship” games, upwards of 150 reporters crammed the press box. They included the big names of the day: Grantland Rice, Damon Runyon, Ring Lardner, Heywood Broun (A.B. 1910), Herbert Reed (known as “Right Wing”) of The New York Tribune, Harry Cross of the Times, George Trevor of The [New York] Sun, plus correspondents from the major magazines such as Collier’s (which published the prestigious All-America team selected by Yale’s Walter Camp, “the Father of Football”) and Harper’s Weekly. In the week before the Yale game, column inch after column inch was devoted to analyses, predictions, lineups, statistics, and features. The game itself got Page One treatment. The Boston Globe “Sportsman” declared in 1911 that “180 football writers and 50 operators will work in the press stand at the Harvard-Yale game Saturday....The only event in sport exceeding the Harvard-Yale game in its demand for wire service is the World’s [sic] Series in baseball, and that is in a class by itself.”

Already a few writers were going beyond play-by-play and glib commentary and, like Haughton, beginning to break the game down. In 1913 Herbert Reed published Football for Public and Player. Like a few of his press-box brethren, Reed had played the game—in his case, at Cornell under Pop Warner. In the era before players and modes of attack and defense could readily be identified, and at a time when the game was in flux, he explicated the action and what lay underneath in sensible language, with illustrative photos and x’s-and-o’s diagrams. It was Reed who, invoking the dictum of General William Tecumseh Sherman about an army, propagated the notion that a team needed a “soul” to be successful. “There was a ‘soul’—call it a personality if you prefer—in the Harvard eleven of 1912, and Captain [Percy] Wendell [A.B. 1913] made the most of it,” Reed declared. Like most of his colleagues, Reed was an unapologetic proselytizer of the sport. “If football is a game...and not so serious a business as many of its opponents believe,” he wrote in the opening chapter of his book, “it is, nevertheless, the most important game we have, the sport that makes the heaviest demand upon every fine quality of the best possible athlete. It is the crucible in which character is moulded at an age when character is in the process of formation—it is, to change the simile, the white light that beats upon a young man’s actions and ideals.”

In contrast to the nationally known names who descended on Cambridge for the big games were the journeymen reporters for the Boston dailies, of which there were a half-dozen in 1913. Since Haughton was so press-averse, they had to rely on other sources and their own powers of observation. George Carens of the Brahmin-oriented Boston Transcript had an in: It was his analysis and his paper’s photos that Haughton had his team scrutinize during Monday practice.

But the true fixture was The Boston Globe’s Melville E. Webb Jr., who eventually (he lived until 1961) would attend 50 Harvard-Yale games. Soon after the stadium opened, with his fellow writers grousing about their substandard accommodations, Webb helped Fred Moore design the press box at the rim of the amphitheatre. Webb made sure to give his colleagues special work areas and writing tables. His efforts were so successful that when Yale and Princeton opened their stadiums in 1914, they consulted with him on the construction of their press accommodations, which in turn influenced later press-box design.

Webb was not a colorful or vivid writer in the mold of Rice or Lardner. But for the daily and Sunday Globe reader in those pre-radio and TV days, he performed two bread-and-butter functions. First, he gave a detailed account of the game that unsparingly noted strengths and weaknesses (including those of the Crimson). He also deployed statistics about as well as one could during those imprecise days. Second, during the week and in postseason summaries, he was most alert to trends. Webb saw through the big crowds to posit that the sport would lose popularity if it did not make it easier to score points. As the rules changed, he noted that bulk and mass, formerly the most important attributes of a powerful team, would need to be supplemented if not supplanted by athletic ability, speed, and versatility. Somewhat in the manner that no one can envision his parents having sex, the modern reader is constantly surprised by the sophistication of Webb and his fellow scribes.

Captain Percy Wendell, A.B. 1913, scoring a touchdown in 1912

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

Captain Percy Wendell, A.B. 1913, scoring a touchdown in 1912

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard University Archives

Charles Brickley, dropkicker extraordinaire

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

Game-bound throngs, circa 1908

Image by Chronicle/Alamy Stock Photo

Spirited sheet music from 1902

Image by Gado Images/Alamy Stock Photo

The varsity footballers attacking the tackling dummy near the Stadium, September 26, 1912

Photography courtesy of the Library of Congress

Once inside the amphitheatre, the spectators were treated not only to a football game, but also to grand theatre. First came the riot of hues. “It was a gold mine for the hawkers,” reported the Times of the scene in New Haven in 1910. “‘Get your colors.’ they yelled until the were hoarse. The flower vendors, with just the kind of flower every girl should wear...Souvenirs of every kind were on tap—little yellow leather footballs pinned on blue and crimson ribbons and large colored letters which could be pinned on the lapel of your coat...” Programs cost 50 cents and were in shape of a football; the contents were loaded with ads for cruises, stylish men’s and women’s “furnishings,” and luxury goods and hotels.

Marching bands would not arrive until after World War I; Harvard’s would be formed in 1919. Instead, the undergraduate sections offered organized cheers and sang school songs. In 1910, when singing “The Marseillaise” (not the French national anthem, but a beloved fight song), the Harvard section, in a precursor of the latter-day “card sections,” caused a sensation by forming, at a signal, a white H.

The programs printed the more popular songs, some passed down through the years, others the product of recent competitions. The 1912 edition contains a few that still are sung: Harvard’s “Our Director” (“Three cheers for Harvard! And down with Yale! RAH! RAH! RAH!”), and Yale’s “Boola,” “Bright College Years” (“For God, For Country and For Yale”), and “Undertaker Song” (“Oh! More work for the undertaker/Another job for the casket maker; In the local cemetery they are very, very busy on a brand-new grave. No hope for Harvard.”). But in the Great Sing-off of 1912, Yale had the composing equivalent of Charlie Brickley in its head cheerleader: one C.A. Porter ’13. Cole Porter composed the new ditty, “Bingo Eli Yale”:

Bingo, Bingo, Bingo, that’s the Lingo!

Eli is bound to win.

There’s to be a victory,

So watch the team begin.

Bingo, Bingo, Harvard’s team can aught avail;

Fight! Fight! Fight with all your might!

For Bingo, Bingo, Eli Yale!

In 1914, the Crimson riposted with the rousing “Ten Thousand Men of Harvard,” written by Alfred Putnam ’18. If not exactly accurate concerning undergraduate manpower—at any given moment, there might be 3,000 in the College, and today there are about 6,000, half of them women—it became the signature fight song, with its foregone conclusion:

Ten thousand men of Harvard

Want vict’ry today,

For they know that o’er old Eli

Fair Harvard holds sway.

So then we’ll conquer old Eli’s men,

And when the game ends, we’ll sing again:

Ten thousand men of Harvard

Gained vict’ry today!

There were many, on campus and off, who debated whether all the energy the young men at these citadels of learning were devoting to sweat, to songs, to cheers, to sophomoric scribbling was properly directed. They occasionally sermonized. ‘“If Jesus Had Gone to the Yale-Harvard Football Game’ was the subject which Rev. Albert R. Williams, pastor of the Maverick Congregational Church, East Boston, spoke on last night,” reported the Globe in 1911. Quoth the Reverend Williams: “If Jesus had gone to the Yale-Harvard game I think He would have much admired the Spartan courage of these men. He would have been glad to find that the players were not all tutti frutti, chocolat eclair, champagne Charlie boys. He would have been glad to find that they were not the up-all-night-and-in-all-day kind....

“If Jesus had gone to the game he would have enjoyed the enthusiastic cheering which came crashing down across the arena, but He would have asked, ‘Is there as much enthusiasm for My work?’”