Buried beneath the ground at the highest point in Poughkeepsie, New York, sits a 36,000-square-foot concrete cistern built in 1923 to hold the city’s water supply. Replaced in 2017 after it sprang a leak, drained and fenced off from passersby, the cistern no longer serves its purpose. Its unadorned, uninviting corner entrance juts from the ground, and its doors are locked. But inside, with its vaulted ceiling supported by slender concrete columns, it is a windowless cathedral. Clap your hands and the sound reverberates for 14 seconds. Sing a note and it floats in the air.

“It’s the most extraordinary space I have ever been in,” said Justin Brown, M.Arch. ’10.

Brown is one of three principals who lead the Poughkeepsie office of the MASS Design Group, a mission-driven nonprofit architecture firm whose founders came together as students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD) 15 years ago. Brown sees the cistern as a unique arts and events attraction in the making, one key among many to unlocking the potential of a city battered by urban renewal a half-century ago and left to live with its injuries since.

A belief in architecture’s capacity to heal animates everything that MASS Design undertakes. So does a blend of opportunistic audacity. That’s been the case from the first, when, as students, its founders successfully designed an unconventional hospital in Rwanda before they became licensed architects. The sense of purpose they shared is evident in the meaning behind the name they chose for their firm: Model of Architecture Serving Society. It’s evident, too, in their ambition. What heals Poughkeepsie, Brown and his colleagues believe, can also heal dozens of other similarly wounded “fringe cities” they have identified across the country—a hypothesis they intend to test next in Appalachia and the South.

Today MASS Design has a $20 million operating budget and employs 207 people who work on more than 100 active projects. Nearly half its total staff, almost 90 percent of them African, are based in Kigali, Rwanda’s capital. The firm’s international portfolio has grown to include the Maternity Waiting Village in Malawi, the GHESKIO Tuberculosis Hospital in Haiti, and the Rwanda Institute for Conservation Agriculture, the world’s first carbon-positive university.

MASS Design’s domestic presence is also growing in scale and scope. The Poughkeepsie office, or studio, was its first U.S. outpost beyond its Boston headquarters. The Santa Fe studio, which focuses on native communities, was created in 2019 (see “Learning from Indian Country,” page 70). The firm’s defining domestic project to date is the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which opened in 2018 in Montgomery, Alabama, a searing monument to black Americans murdered in lynchings and victimized in other ways because of their race. “The single greatest work of American architecture of the 21st century,” one critic called it.

After just 15 years, MASS Design’s improvisational, mission-driven founders made it the American Institute of Architects’ 2022 firm of the year.

In 2022, the American Institute of Architects named MASS Design its firm of the year, praising it for producing distinguished architecture while working “tirelessly to ignite systemic change in the built environment.”

“It’s great that they’re getting their flowers, so to speak,” said Imari Paris Jeffries, the executive director of Embrace Boston, a current client who described the firm as “above ahead of its time.”

Birth in Butaro

Michael Murphy, M.Arch. ’11, uses a single word to describe the birth of MASS Design: alchemy. The term also serves to describe his transformation from English literature major to Harvard architecture student. Shortly after Murphy earned his undergraduate degree, his father was diagnosed with cancer and given only weeks to live. At home in Poughkeepsie, on a death watch, Murphy picked up the restoration project his father had undertaken on the family’s house. At three weeks, his father was still alive; at six weeks, he joined in the work. A year and a half later, Murphy’s father was in remission and the renovation was complete.

Michael Murphy

Photograph by Agaton Strom

“Working on this house with you, it saved my life,” his father told him. “It healed me.” Suddenly Murphy knew his calling: he would become an architect.

That was in 2005. In December 2006, two days before his first semester final review at the GSD, Murphy attended a lecture by Paul Farmer, co-founder of Partners In Health. (Farmer, who became Kolokotrones University Professor, died in 2022.) After the lecture, Farmer told Murphy that Partners was building hospitals, clinics, and schools in underserved regions of the world without help from architects. Murphy emerged from his review to learn that his father had gone into septic shock, and he sat with him the next day in a prestigious hospital, wondering how “this thing that kept him alive is also just this horrifically designed place.”

Alan Ricks

Photograph by Liz Linett

His father died in the spring of 2007. Murphy spent the summer with Farmer in Butaro, Rwanda. That fall, when Farmer’s assistant called to ask if Murphy could design a hospital, he turned to his classmates—literally; he took the call at the GSD—and asked if they could help. Alan Ricks, M.Arch. ’10, was among those who said yes. “It didn’t feel like such a monumental decision at the time,” he said. When two others, Marika Shioiri-Clark, M.Arch. ’11, and Alda Ly, M.Arch. ’10, traveled with Murphy to Butaro for his second visit, they already thought of themselves as co-founders. But in March 2008, when the students presented their first plan to Farmer, he told them it looked like a barracks.

At the same time, the world economy collapsed, bringing an abrupt end to the “starchitect” era of stunning designs born in lush years, taking job prospects with it and highlighting the question of what the purposes of architecture should be. Murphy, on student loans, faced financial hardship on top of personal loss. Taken together, he said, all those elements “gave me the confidence or bravery—I don’t know what the word is—but I wasn’t afraid to say, ‘F— it, let’s just go to Rwanda and see what Paul needs, to be of service.’”

David Saladik

Photograph by Liz Linett

Supported by Harvard fellowships, Murphy took a year off. David Saladik, M.Arch. ’10, who joined him for the summer, was among a half-dozen classmates who spent time in Butaro, while others contributed design help from home. “Being immersed in that place and that community and just seeing the need and how transformative a hospital could be—it was hard for me to think about going back and doing a more traditional track of design,” said Saladik. They absorbed Farmer’s belief in beauty as a form of justice that promotes dignity and that should be available to everyone. Their thinking was not hobbled by the way hospitals were typically designed. “The lack of specialization in Rwanda necessitated taking ownership as a team—the client, us—over every decision,” Ricks said. “What that revealed was that every decision is an opportunity to have positive social and environmental impact.”

Rwanda’s Butaro District Hospital—light-filled, naturally ventilated, and with natural views: early evidence of MASS Design’s “alchemy”

Photographs by Iwan Baan

By the spring of 2009, the students had also learned enough to recognize that they didn’t know how to actually build the hospital. Murphy began asking different questions: “How do we bring on employees? How do I raise money? And I took a significant pivot to try to find someone to carry it forward.”

Sierra Bainbridge

Photograph by Tony Luong

That someone was Sierra Bainbridge, a landscape architect who had come to the GSD to teach a class. While overseeing construction of New York City’s High Line park, she began moonlighting on the Butaro project. In July 2009, two weeks after finishing the first phase of the High Line, Bainbridge flew to Rwanda, where she became—architecturally speaking—the professional in the room.

The 150-bed Butaro District Hospital opened in 2011. It looks nothing like an institutional American equivalent, beginning with its landscaped campus of low buildings arranged on a hilltop around an old umuvumu tree, thought to have marked the spot where the local king once engaged with his people. The walls are faced with volcanic field stones so common they are a nuisance for farmers, fashioned by local craftspeople into fits so precise it’s difficult to slip a sheet of paper between pieces. High-volume, low-speed fans encourage the outside air to flow in, up, and out of the buildings, providing natural ventilation. Patient beds are placed in the center of the wards, each looking out through a large window toward green hills and valleys.

One project followed another. MASS Design incorporated, to be sustained over the years by philanthropic fundraising used to support research, encourage risks, and seed building projects for nonprofits before transitioning to the traditional fee-for-service model once the projects were funded. As the firm grew, Murphy became executive director and Ricks chief operating officer, while Saladik led healthcare work and Bainbridge the landscape studio. Shioiri-Clark and Ly went on to found their own practices, as did another early contributor, Ryan Leidner, M.Arch. ’10. Over time, more classmates joined, as did architects with other backgrounds who now play leadership roles.

One day in 2012, Murphy got an email from a nonprofit leader in Poughkeepsie. You’re doing this great work overseas, he wrote; what about us?

Healing the Wounded

Chris Kroner and several others were working in the two-story MASS Design office in Poughkeepsie one night in 2018 when the seven-story building next door fell on top of them. Empty, hollowed by years of neglect, it toppled in a windstorm. Their own roof held.

The channelized, trash-choked Fall Kill as it looks

Photograph by John Bartelstone

The collapse embodied all that befell Poughkeepsie after the federal government made a massive urban renewal investment in the 1960s. Two three-lane arterials built to speed traffic through the city rendered the downtown an island of underinvestment. Buildings were demolished to make way for private development that never came. The call Murphy fielded followed Hurricane Irene, which flooded the Fall Kill, a river channelized by the Army Corps of Engineers and choked by trash.

Initially, MASS Design conducted its work in Poughkeepsie from Boston. Plans for reimagining the Family Partnership Center—a home for nonprofits damaged in the Fall Kill flood—moved forward under Justin Brown’s leadership, as did a workforce housing project and the renovation of the city’s historic Trolley Barn, reborn as an arts and event center.

Chris Kroner

Photograph by Liz Linett

But as in Rwanda, deep success required deep commitment. Momentum didn’t build until Kroner, a New York City designer, and two interns came to Poughkeepsie in 2016—an initiative that grew out of a class he co-taught with Murphy at Columbia. Their initial focus: the Fall Kill, which once powered Poughkeepsie’s industries. After two weeks of research, they opened an exhibit on the river’s past and present intended to foster community discussion about its future.

Caitlin Taylor

Photograph by Tony Luong

Similar research, exhibits, and community engagement on the cistern and urban renewal came later. In 2018, Caitlin Taylor joined the office. A Yale professor and “farmer slash architect,” she focused on research and design work related to fostering regional food systems, leading to the Poughkeepsie Public Market: a food hall, bar, event space, and restaurant in a renovated brick building, which opened last year. Brown moved to the city in 2019. Together, he, Taylor, and Kroner are responsible for what is now a Main Street office of 13 at work on 16 projects.

The community-committed Poughkeepsie team members envision their work as “a kind of replicable model” for repairing battered cities.

“We’re really looking at our work here in this city as a kind of replicable model of what we did in Butaro,” Brown said, “which is investing design in building consensus with the people that live here about what should be and then raising the capital to build as a secondary initiative.”

Their approach largely relies on collaboration with nonprofits and local government. Scenic Hudson typifies the first. Long focused on land conservation along the Hudson, the organization decided to seek a larger role in river cities at about the time MASS Design took root in Poughkeepsie. “One thing led to another, and the relationships just started to develop,” said Jason Camporese, Scenic Hudson’s chief financial officer.

Justin Brown

Photograph by Tony Luong

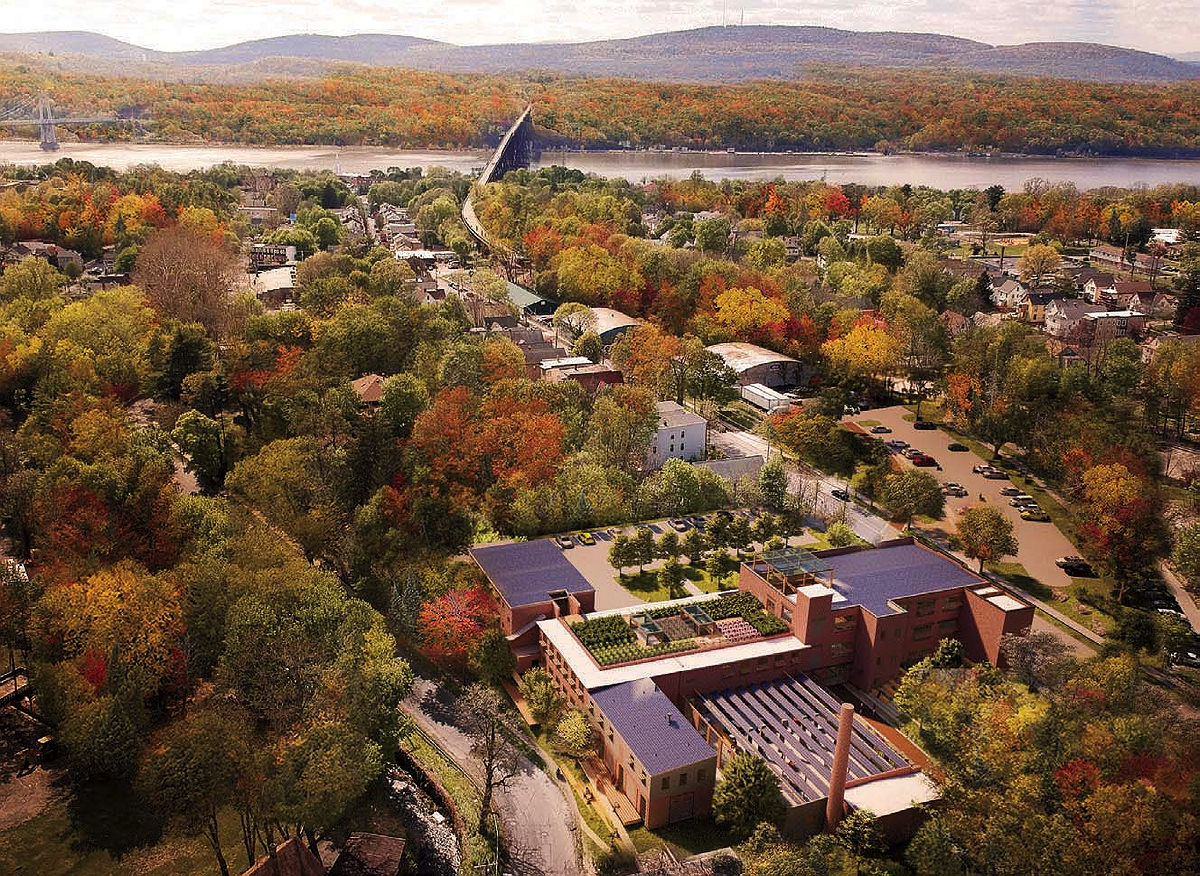

Today, MASS Design serves as architect for Scenic Hudson’s new $25 million headquarters in a renovated factory building on the Fall Kill, across the street from the east entrance to the region’s biggest tourist attraction, the Walkway Over the Hudson state park. Every year, more than 600,000 people visit the walkway, an old rail bridge—then leave. With a park along the Fall Kill and exhibit space, room for public events, conferences, and meetings, the headquarters has the potential to serve as the first bead on a string of redevelopment projects leading along a liberated river to the heart of the city. With its reliance on natural ventilation and light, as well as the adaptive use of an undervalued local resource—abandoned brick buildings—the design reflects Butaro’s lessons.

A second project suggests the promise of collaboration with local government: the Youth Opportunity Union, or YOU, to be built on the site of a former YMCA. Aside from a jail, the YOU represents the first public infrastructure investment in downtown Poughkeepsie since urban renewal. It grew out of a 2019 community meeting hosted by the Family Partnership Center. Kroner was among those there who overheard three high school girls bemoan the lack of a community center for kids. “There just isn’t a safe place for us,” one said.

Renderings of the Scenic Hudson headquarters (top) and Poughkeepsie Youth Opportunity Union (above), knitting the city back together

Images courtesy of MASS Design Group

Kroner helped assemble what became a coalition of 16 organizations to explore possibilities. Dutchess County provided seed funding and eventually purchased the property from the city. MASS Design won a competition for the project and the county committed $25 million to build it, to be supplemented by private fundraising. MASS Design’s plan includes a pool, basketball court, fitness center, childcare center, intergenerational playscape, and space for enrichment classes—all set in an inviting open design. Ahead comes the challenge of aligning those features with a final budget.

“We all have this feeling that we’re going to be part of this world-class experience,” said Bill O’Neil, the chief county executive. “I won’t call it a building.” O’Neil said MASS Design’s creativity and commitment to the city overcame paralyzing habits of conflict that have held Poughkeepsie back. “It draws you in,” he said of the firm’s approach. “You want to understand it, you want to be part of it.”

Success in Poughkeepsie is a long-term proposition, Kroner said, because it entails reversing decades of neglect. “Some of our biggest projects need to happen in order for the city to find that catalytic force,” he said. “That’s why I’m hoping to see things like the school system, things like development, start to create a smaller engine of activity that is self-sustaining again. That would be a really incredible measurement of success.”

Memorializing Injustice

On his way from the Park Street T stop to work, Jonathan Evans, M.Arch. ’10, passes The Embrace, a memorial to Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King on the Boston Common that was dedicated in January. He has seen as many as two dozen people at the memorial on a winter weekday morning. Fathers hug sons beneath it. Couples hug each other. Some are moved to tears. “Tourists,” Evans said. “People working at restaurants down the street that are still in full uniform. You’ve got young, old—all walks of life. It’s amazing.”

A rendering of the site plan and setting for the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial in Boston

Image courtesy of MASS Design Group

The Embrace is inspired by a photograph of the Kings, who met in Boston, at the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony in 1964. The memorial depicts only the Kings’ shoulders, arms, and hands, perched on their elbows, wrapped in a hug. No heads, no faces, no torsos—a 22-foot-tall monument concerned not with rendering recognizable people but love, an emotion central to the Kings’ lives and purpose. It is the work of sculptor Hank Willis Thomas on behalf of Embrace Boston, which conceived of the memorial and raised the money for it. MASS Design collaborated with Thomas from the start, and Evans, who works in the firm’s Boston headquarters, served as lead architect.

MASS Design’s focus was the setting and the larger story the memorial could tell. The circular plaza on which The Embrace sits is made of 1,300 diamond-shaped stone tiles with contrasting finishes. From above, it evokes an African American quilt and the shared “garment of destiny” of which King famously wrote. The names of 65 Boston civil rights leaders are engraved in the tiles, and a quote from Coretta Scott King about love as a call to action is featured on the low wall around the plaza.

Everyone involved in the project recognized Thomas’s design as a risky, provocative choice—including the sculptor himself. “I remember showing Michael (Murphy) the rendering and saying, ‘I don’t know if I can do this without the heads,’” Thomas said at a forum before the memorial’s unveiling. But the reaction within the firm was positive. “There are so many men on horses,” Evans said of traditional memorials. “We wanted to force people to snap out of the matrix and realize there is something bigger at play.” Their joint submission won a design competition, and Evans led a team of 20 at MASS Design who saw the project through.

Initially, the online reaction to The Embrace was a self-fueling cyclone of criticism and mockery; one art critic called it an awkward missed opportunity. But Evans’s commitment to the design is unshaken—in part because of how he sees people reacting to it. The same is true of Imari Paris Jeffries, Embrace Boston’s executive director, who was struck by the effect the memorial had on the crowd that gathered there for a vigil to protest the beating death of Tyre Nichols at the hands of the Memphis police two weeks after the unveiling. It felt, he said, “like an open-air sanctuary.”

Like Evans, Jha D Amazi, who leads the firm’s Public Memory and Memorials Lab, is black, and the opportunity The Embrace represented has deep personal meaning, because it elevates the experience of blacks in Boston in a way no other monument does. “It is such a blessing,” she said at the forum, “a calling, to know that I can be part of conversations that shift the landscape in which my black son will be raised.”

MASS Design’s memorials lab is also responsible for such works as the Gun Violence Memorial Project, another collaboration with Thomas, unveiled in Chicago in 2019. But it’s a third collaboration involving Thomas, among other artists, that has drawn the most acclaim.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the firm’s best-known U.S. work

Image courtesy of MASS Design Group

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery is a hilltop project of the nonprofit Equal Justice Initiative, led by the civil rights activist Bryan Stevenson, M.P.P.-J.D. ’85, L.L.D. ’15. It is the first national memorial to the 4,400 black Americans killed by white mobs between the Civil War and 1950. Many were lynched, others burned alive or beaten to death. MASS Design joined the effort that brought the memorial into being between 2015 and 2018. “This one felt like a reality so important and an idea so strong and a project so necessary that we just didn’t eat or sleep for three years,” said Justin Brown, who served as project architect. “There is nothing like it in the country,” wrote the New York Times. “Which is the point.”

The heart of the memorial is a pavilion held up by six-foot-tall rusted steel pillars, each bearing the name of a county where racial killings occurred and the identities of the victims. As a visitor enters the pavilion, the floor falls away, with more pillars, now suspended, overhead—leaving the unmistakable impression of walking beneath corpses. There are more than 800 pillars in total. In the central courtyard, it’s the visitors who feel as if they are being judged by the pillars, as silent onlookers. The whole amounts to an immersive experience of recognition, discomfort, reflection, and transformation—a confrontation with the past intended to create hope for the future. A second set of matching pillars rests on the ground outside; EJI invited every county to claim its own pillar and bring it home.

The memorial changed Brown’s understanding of architecture. “I can’t think about a building as an object anymore, but as a process, something that’s evolving and changing,” he said. “What is built is important, of course, but that’s just the beginning.”

The same could be said of MASS Design itself.

MASS Redesign

Talk to MASS Design’s senior leaders long enough, and they’re likely to invoke an Alan Ricks mantra: “Our longest-running project is the design of our practice.” It’s more than a slogan. “We’re hyper-self-critical,” said Sierra Bainbridge. The habit of change was called upon in a new way late last year, when the charismatic Murphy stepped away from an organization he not only co-founded but came to represent in the public eye.

His new venture: a for-profit catalyst intended to address the limits of what MASS Design’s successes have revealed. Imagine, Murphy said, a nonprofit bringing about great changes in its community. “They don’t benefit from the value they create,” he said, “because those who have access to the capital come in and are able to acquire the land and then develop it.”

Murphy, who remains on the firm’s board, believes that can change—with the help of a new entity that works with nonprofits not only to design a project, but to help them step beyond traditional philanthropic fundraising to establish an ownership stake in what they produce. By assembling investments from philanthropy, foundations, and those in the private sector willing to appreciate the value of social as well as financial returns, he said, “You could compose the capital in a different way than straight philanthropy or straight investment.”

To Murphy, it is a new way of architecting a better society. For legal and practical reasons, he said, only a for-profit venture can play such a catalytic role; he believes the results could be transformative. Even the people whose neighborhoods are affected by a project could share in the value that results. For nonprofits, including MASS Design, it could alleviate the slog of raising money every year by creating an endowment.

As for the firm’s prospects, Murphy expressed no doubts. “We have an incredible team of people,” he said. “I’m so excited to see what they can do with it.”

The ability to bring great people together is one of many attributes Murphy’s colleagues said they will miss. At the same time, the firm’s leaders see an opportunity to make its collaborative essence clearer. That identity is reflected in a new leadership team of three co-executive directors. Christian Benimana, a Rwandan architect, is responsible for the African portfolio of work, Ricks for departments that run across the organization, and Patricia Gruits for the U.S. studios.

Together they will help manage the challenges that any maturing organization faces—among them maintaining the willingness to take risks that led to success in the first place. Living up to MASS Design’s ideals poses challenges, too, from continually pushing innovative design to measuring the effectiveness of buildings in serving clients and the environmental and social costs of materials used. “We have great thinkers and designers up and down the organization,” said Ricks. “How do we tell that story?” Fulfilling MASS Design’s commitment to the victims in society in its own hiring, Evans said, is another “robust topic of conversation.”

Asked if MASS Design, at 15, risks ossification, Bainbridge laughed. “A little ossification might not be such a bad thing for us,” she said, “just for stability to allow people to have space to be curious.” As for losing its restless startup spirit altogether, she said, “I don’t think that’s going to be a big concern.”