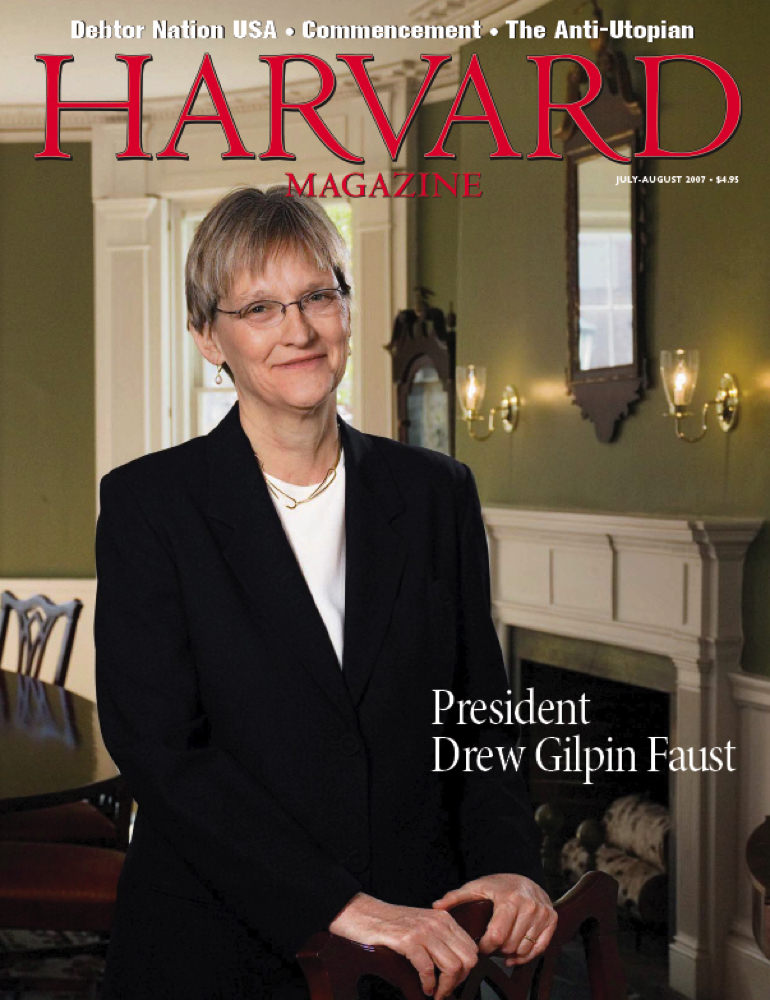

Drew Gilpin Faust, who assumed office as Harvard’s twenty-eighth president on July 1, 2007, announced today that she would conclude her service at the end of the next academic year, June 30, 2018. Her planned retirement is a logical transition:

- The date coincides with the scheduled conclusion of The Harvard Campaign (which has raised $8 billion so far).

- The change in Massachusetts Hall mirrors the orderly transition effected by Neil L. Rudenstine, who announced in May 2000 that he would conclude his presidency in June 2001. That was a similar institutional moment: he and Harvard had celebrated the conclusion of the $2.6-billion University Campaign on May 12 and 13.

- Announcing the path to a new administration now provides the enlarged and reconstituted Harvard Corporation (whose reform is one of the signature accomplishments of Faust’s tenure) with plenty of time to conduct a thorough, measured search for her successor—while also creating opportunities for Faust to complete more items on her agenda. (These no doubt include remaining big-ticket fundraising priorities such as the Allston science and engineering center, undergraduate House renewal, the Graduate School of Design’s addition, renovation of the Divinity School’s Andover Hall, and further buttressing of financial-aid endowments.)

From a personal standpoint, the transition should have the welcome effect of enabling Faust to contemplate the end of a grueling travel schedule (fundraising events worldwide, and this year, frequent trips to Washington to discuss changes in immigration policy, federal funding for basic research, and more), and to enjoy time with her husband, Charles Rosenberg, Monrad professor of the social sciences (an historian of medicine), and family members and friends. Faust turns 70 this September, and Rosenberg will be 81 in November.

An assessment of Faust’s presidency must naturally await its conclusion. Important milestones during her administration are covered in several thematic sections below (fleshing out some of the summary points in the message from the Corporation’s senior fellow, William F. Lee). These are followed by some context on the Harvard challenges that may be on Corporation members’ minds as they organize for a search, and on any successor’s list of priorities.

“A Scholar in the House,” Harvard Magazine’s profile of Faust as she assumed the presidency, appears here; coverage of her inaugural festivities and installation appears here.

In a message to the community disseminated this afternoon, Faust said of her timing, decision, and term in office:

It will be the right time for the transition to Harvard’s next chapter, led by a new president.

It has been a privilege beyond words to work with all of you to lead Harvard, in the words of her alma mater, “through change and through storm.” We have shared ample portions of both over the last decade and have confronted them together in ways that have made the University stronger—more integrated both intellectually and administratively, more effectively governed, more open and diverse, more in the world and across the world, more innovative and experimental. The dedication of students, faculty, and staff to the ideal and excellence of Harvard, and to the importance of its pursuit of Veritas has made all this possible. I know this commitment will carry Harvard forward, from strength to strength, in the years to come.

I am deeply grateful to every member of this community for the honor of being your president and for the support and, indeed, joy you have given me. I look forward to being able to thank you directly in the course of the next year and to using the months that remain in my term to join with you in continuing to advance our shared purposes. There is much work to be done: combatting the ongoing threat to federal funding for research; completing the capital campaign and ensuring its support for our most important priorities; attracting and sustaining the most talented faculty, students, and staff; advancing the work of inclusion and belonging that enables every member of our community to thrive; helping to realize the dreams of the many remarkable individuals who together are Harvard. I look forward, with all of you, to seizing every opportunity and confronting every challenge in the year ahead. And for this extraordinary, beloved University, I cherish an enduring wish, captured in the closing lines of the speech I delivered in 2013 to launch the campaign:

May Harvard be as wise as it is smart,

as restless as it is proud,

as bold as it is thoughtful,

as new as it is old,

as good as it is great.

In a separate message, senior fellow Lee wrote:

I’d like to offer a few personal observations about President Faust, as a person and a president.

I remember vividly joining a dinner in 2006 with fellow members of the Presidential Search Committee—I was one of three members of the Board of Overseers appointed to join the six members of the Corporation—to hear from the deans of Harvard’s various schools and faculties about priorities for the search. I was seated next to the dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study—Dean Drew Faust. We had never met. Over the course of our meal, I was deeply impressed by her contributions to the larger discussion, all of which reflected wisdom and insight. But, more important, we had the most interesting personal discussion concerning our upbringings, our families, the Civil War, and a book she was in the process of completing—a book that would go on to be a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. From that day to this, I have repeatedly witnessed how the qualities that impressed me at that first meeting—her intelligence, her depth, her warmth, her compassion, and her extraordinary ability to communicate, including her ability to listen to and understand what others are saying—are evidenced in all she does and in how she leads.

For the last 10 years, she has approached every day with a singular purpose: to ensure that Harvard remains the preeminent academic institution in the world by constantly driving Harvard forward.

In 2017, many of us might forget how challenging that task was for the first several years of her presidency. She came into office after a period of strife and controversy on campus, and she quickly restored trust and a sense of common purpose. She was also able to introduce her own personality and leadership style—characterized by calm, candor, and listening—to the campus as she ensured forward progress.

But just over a year later, Harvard faced an even more profound challenge—as did the rest of the world—in the form of a global financial crisis. While the crisis challenged every major research university, Harvard was particularly hard hit. Drew acted swiftly and decisively to minimize exposure, curtail risk, and chart a disciplined and responsible course forward. She made hard decisions—and unpopular ones.

She also insisted on modernizing the governance of the University, and she did. She assembled a leadership team of top-shelf talent from within the academy, from industry, and from the non-profit sector. She recruited superbly talented, diverse, and collaborative deans. And, most critically, she trusted and empowered them all to carry Harvard forward. In return, they trusted her, and they, too, gave Harvard their all, inspired by her example.

Notwithstanding the profound challenges early in her tenure, Drew never lost sight of her vision for Harvard. She relentlessly pursued those initiatives she believed would make the University still better—One Harvard, the expansion of financial aid, the growth of science and engineering, the support of innovation and entrepreneurship, and a rededication to the arts and their critical role in a true liberal education—with just the right mix of patience and prodding, optimism and urgency

Let me recount one final vignette. At the press conference announcing her appointment as Harvard’s twenty-eighth president, Drew was asked by a reporter how it felt to be “Harvard’s first woman president.” She answered quickly and decisively that “I am not the woman president of Harvard. I’m the president of Harvard.” At the time, it was viewed as a great response; score one for feminism and equality. What I have come to appreciate, however, is that her comment revealed something much deeper: her strong aversion to labeling people, her belief that Harvard must honor both inclusion and individuality, and her insistence that every person who is a member of this community knows and feels that he or she belongs, that “they, too, are Harvard.” That commitment—and her own path-breaking example—has been a hallmark of her presidency, and Harvard is immeasurably better for it.

In a brief telephone conversation, referring to the University news release on Faust’s presidency that accompanies his message, Lee said, “The collection of accomplishments and achievements is a reflection of her character as a leader.” He called Faust “one of the most extraordinary people in the world and the most extraordinary person I’ve ever worked with.”

Looking ahead, he said, the first order of business is following through on “an enormous number of important things she wants to accomplish before she steps down,” followed by celebrating Faust’s presidency and her achievements on Harvard’s behalf. The third priority, inevitably, is mounting a search to assure that “the transition is smooth and in the best interest of Harvard.”

To that fundamental task the enlarged Corporation brings broader “experience, expertise, and judgment” than were available to the senior governing board in 2006-2007, and more channels to reach out for ideas and suggestions. Lee noted the “unique” asset of having four university leaders as Corporation members (Faust; Wellesley and Duke president emerita Nannerl O. Keohane, whose service concludes June 30; Tufts president emeritus Lawrence S. Bacow; and Princeton president emerita Shirley M. Tilghman) and said, “We’d be crazy not to get the benefit of that.” Bacow and Tilghman will obviously be involved in the Corporation’s deliberations, he continued, and he expects that Keohane’s counsel will be sought as well after she formally departs.

The Corporation is preparing for its summer retreat, Lee said; its agenda, now being formulated, will obviously include this new item.

“Knitt Together…As One”

Drew Faust at the outset of her Harvard presidency

In her installation address in October 2007, Faust—ever the historian—drew upon Governor John Winthrop’s 1630 guidance to the settlers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, “A New Modell of Christian Charity.” She twice quoted from the same passage Winthrop’s call to the settlers to be “knitt together, in this work, as one.…”

Beyond invoking a sense of community appropriate for any institution, Faust was perhaps addressing her first great challenge: to restore comity and a spirit of cooperation to an institution left divided by the controversial presidency of Lawrence H. Summers, abruptly concluded with his resignation, effective in mid 2006. During the succeeding year, Derek Bok—returned to Mass. Hall as interim president—resolved many pending matters and unwound or delimited initiatives that had not taken root or found their financial footing. He also advanced several major projects, including construction of an enormous science complex along Western Avenue, opposite the Harvard Business School campus: a $1-billion-plus statement that the University’s campus growth in Allston (on land purchased beginning in the 1980s during Bok’s administration) was boldly under way.

Faust by all accounts built a consensual group of deans and senior administrators, and established inclusive processes of soliciting opinions and formulating policies. In the meantime, the academic work and aspirations of the community advanced briskly—encouraging portents of Harvard’s bright prospects after a period of discouraging disruption:

- Even before her installation, the division of engineering and applied sciences completed its transformation into a school (SEAS), an indication of growing research prowess and student interest in those fields.

- That November 1, Faust announced a University initiative to determine how Harvard might invest in teaching about and supporting creativity, performance, and artistic practice—clearly, a major initiative meant to bolster the institution’s presence in fields of wide interest, but little represented in the curriculum. Cogan University Professor Stephen Greenblatt chaired the task force.

- Six weeks later, Faust announced a sweeping enhancement of undergraduate financial aid, putting in place an income-based standard for family payments and liberalizing aid by eliminating loans and excluding home equity in calculating ability to pay. The new formula prompted competitive responses from peer institutions nationwide—and very significantly upped the ante for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), which would have to use unrestricted funds to fulfill its expanded aid obligations to students in need.

- The following spring, FAS formed the committee to plan renovation of the undergraduate Houses—a massive construction project. The art museums prepared to close for a five-year renovation and reconstruction of the Fogg building at 32 Quincy Street, into which the separate Sackler and Busch-Reisinger collections would be consolidated.

President Faust, followed by interim president Derek Bok, at her installation

All signs pointed toward an auspicious future—just the sort of opportunities to elicit energies and enthusiasm for common purposes—and, in an operational sense, a capital campaign to pay for everything. Any such drive would be unusually ambitious, following the longer-than-usual interval since the conclusion of the University Campaign in 1999 (as the truncated Summers presidency disrupted the fundraising calendar). As Radcliffe Institute dean, Faust had embraced fundraising—and had also, in pursuit of the new mission as an institute for advanced study, rationalized the existing administration, cutting positions and costs and redeploying resources.

If there was a cloud on the young administration, it hovered on the horizon, over Boston: in August, just after Faust took office, Harvard Management Company (HMC) reported tremendous results, as a 23 percent investment return for fiscal year 2007 helped swell the value of the endowment by $5.7 billion, to $34.9 billion. Just three weeks later, however, Mohamed A. El-Erian, HMC president since early 2006, announced his resignation at year-end, to return to his former employer. Although HMC still had a little more momentum (in the year ended June 30, 2008, an 8.6 percent investment return led to a further $2-billion gain in the endowment’s value), Harvard’s sunny plans were about to be blotted out, as the looming financial crisis and severe recession ushered in severe challenges for which almost no one worldwide could have been prepared.

Whiplash: A New (Financial) World Order

On December 2, 2008, Faust and executive vice president Ed Forst, a Goldman Sachs alumnus, posted a memorandum stating that the endowment’s value had declined 22 percent through October 31. It continued, “even that sobering figure is unlikely to capture the full extent of actual losses for this period, because it does not reflect fully updated valuations” for certain classes of assets, “most notably private equity and real estate.” As this magazine noted, “The numbers may seem abstract, but their consequences are real. The endowment was valued at $36.9 billion last June 30, at the end of fiscal year 2008; in that year, Harvard’s total revenues were about $3.5 billion, with some $1.2 billion (34.5 percent) from endowment-income distributions. Such distributions are much the largest source of operating revenue today, far outstripping tuition and fee revenues (20 percent), sponsored support for research (19 percent), and other income.” The story was titled “Harder Times.” Indeed.

In the event, the endowment depreciated $11 billion during the year, and the University incurred additional losses in the billions, reflecting the costs entailed by interest-rate swap agreements put in place in anticipation of huge borrowing to build the Allston campus rapidly; commitments to make future investments with outside money managers—which Harvard was now in no position to fund; and the fact that the University had invested much of its liquid reserves alongside the endowment, making it difficult to pay its routine bills when those reserves suddenly declined in value and liquidity dried up.

At the same time, of course, FAS was shouldering its expensive new financial-aid obligations—which only grew as the recession drained family incomes; the institution’s commitment to aid was unshaken. The Allston science complex was sopping up hundreds of millions of borrowed dollars, with perhaps a billion dollars more to be tapped. Both the art museum and a large Harvard Law School facility were under way. Lacking other good options, Harvard borrowed $2.5 billion at the relatively high interest costs then available, knowing that it would face additional interest and principal payments even as revenues shrank; the University needed the money. (Interest expense in fact more than doubled from fiscal 2008 to a peak of $296 million in fiscal 2011—a painful reminder of dues to the past.)

At the moment she was appointed president, Faust faced the challenge of healing the community, but otherwise seemed burdened principally by the need to choose among appealing opportunities. Now she, her management team and deans, and the Corporation had to pivot: it was one thing to “knitt together” a community little accustomed to fiscal constraint, but utterly another to introduce real limits to growth.

Much of the adjustment was accomplished by reining in the anticipated trajectory of future expansion. Annual distributions from the endowment, which deans had previously expected to increase, in fact declined by a couple of hundred million dollars from fiscal year 2009 to 2011. FAS initially envisioned a budget deficit of some $200 million, assuming it continued to enlarge the faculty ranks, raise compensation, and so on. Once it refrained from making those investments, the path toward a more sustainable fisc became apparent. (There were, to be sure, de facto freezes on faculty growth and on compensation, stretched-out investments in capital projects and new academic programs, and modest staffing reductions and retirement incentives, if no wholesale layoffs. And there were tensions aplenty: Provost Alan Garber, often the bearer of such news, had tough FAS faculty meetings when he announced changes in the libraries and staffing consolidations, a less-rich employee medical-benefits plan, and the elimination of retirement financial-planning services for faculty members.)

Two events provided the most tangible evidence of the new order. Faust’s arts task force had the unhappy experience of presenting its report—calling for new degree programs and facilities, premised on “substantial fund-raising”—eight days after she and Forst made their sobering announcement. She and Greenblatt expressed the hope that the economic downturn would be short-lived, clearing a path toward effecting recommendations that both of them must have welcomed as an essential vision for the University—but there would be no immediate implementation. A year later came the inevitable decision to halt construction of the Allston science complex indefinitely (see “Arrested Development,” March-April 2010) and, more broadly, to pause campus planning for a thorough reevaluation.

Rebooting

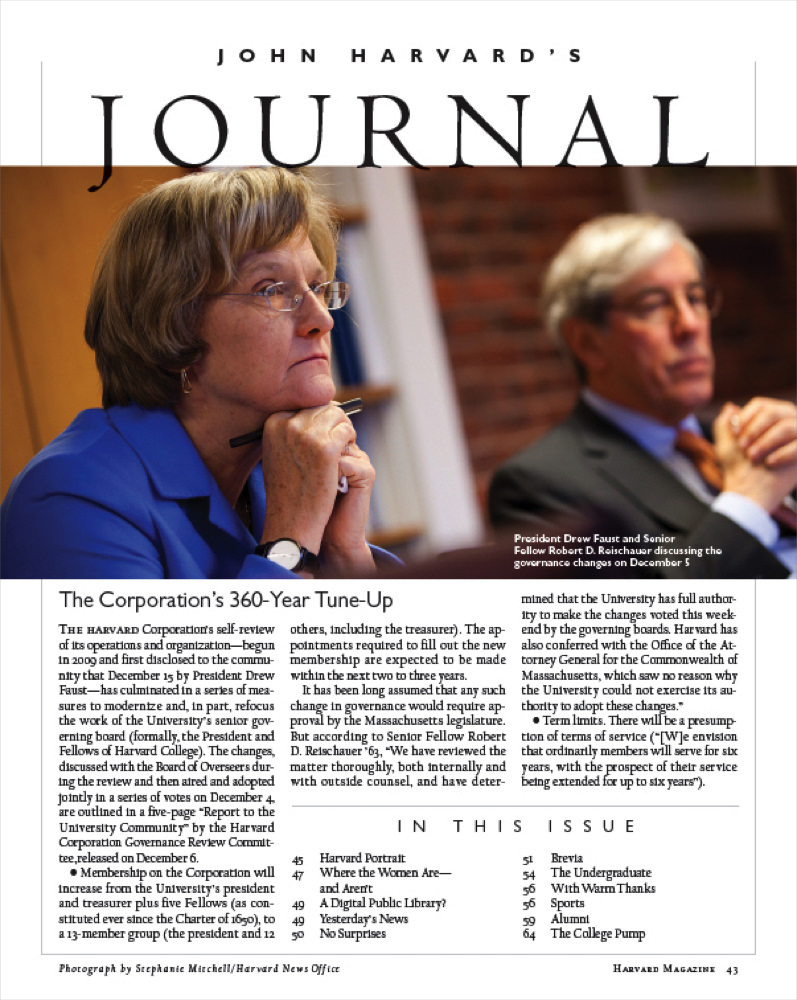

In December 2010, Faust and senior fellow Robert D. Reischauer unveil momentous changes in University governance.

It is useful, if simplistic, to view the larger reorientation steered by Faust and the Corporation in three categories: the impossible, the necessary, and the inevitable.

The impossible task was overhauling University governance—a 360-year-old edifice—so that the then-seven-member Corporation could in fact exercise its fiduciary responsibilities and organize itself to lend strategic guidance to the institution’s leaders: in other words, to pull back from assuming unrecognized, existential financial risks and to move decisively toward some more predictable, productive governance appropriate to a complex, multibillion-dollar enterprise operating in the twenty-first century.

The announcement on December 6, 2010, that the Corporation would be modernized—by enlarging its membership to 13, with more diverse, broader expertise; forming standing committees pertinent to its fundamental responsibilities; and introducing new procedures to improve self-governance and enhance its access to critical information—was of fundamental importance. It was Harvard’s recognition that the leadership and financial crises of the decade then ending were deep-seated and structural, and that their root causes had to be addressed. Although the full impact of the changes will come into view only over decades—as the Corporation’s membership changes, as it refines Harvard’s strategy and oversees policy, and as it manages the University’s leadership successions—the effort itself seems certain to rank high among the legacies from the Faust era.

The necessary tasks were related to, and in part accommodated by, the governance reforms. The Corporation’s new finance and facilities and capital planning committees were complemented by changes in Harvard management. There are now consolidated multiyear budgets and routine reporting procedures, institution-wide planning for capital projects, much stricter hurdle rates for funding capital projects before they can begin, and changes in accounting so schools depreciate facilities appropriately on their books and in their budgets (in the hope of avoiding future problems like the $1.4 billion in deferred maintenance on the undergraduate Houses). Such disciplines aren’t especially newsworthy, but their absence contributed to Harvard’s financial crisis; bearing the cost of putting them in place is part of running the place responsibly.

The inevitable was the size and shape of that capital campaign—very much anticipated by the revised Corporation’s decision to form a joint committee on alumni affairs and development with the Board of Overseers, and to bring into its ranks some new members with extensive connections in the financial community and experience in asking for big gifts, with gusto.

“At Harvard…”

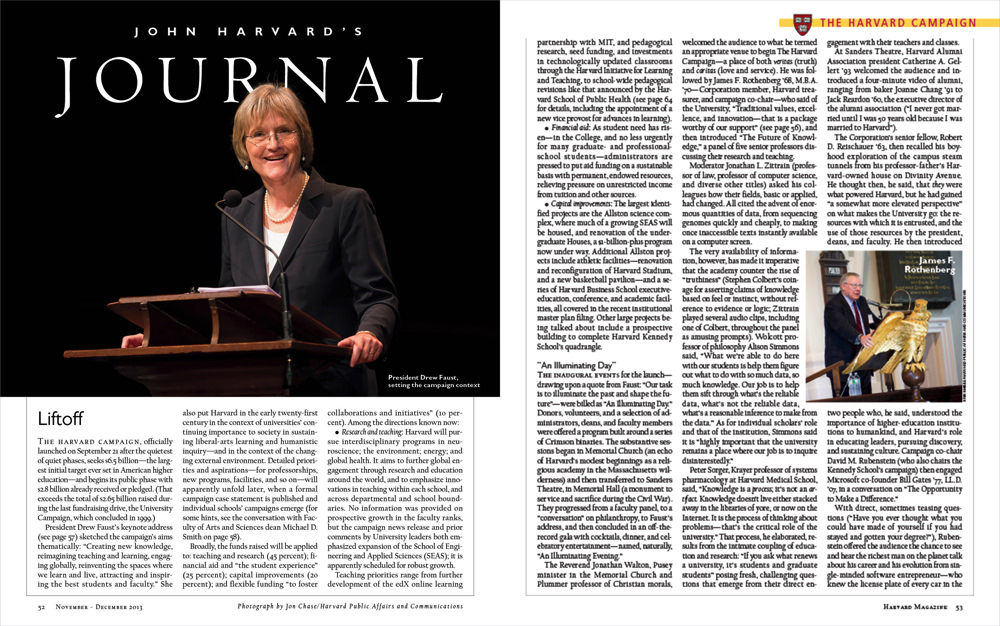

The Harvard Campaign, begun quietly in 2011 and announced with raucous celebration on September 21, 2013, set out the unheard-of goal of $6.5 billion—a sum the fundraising leaders pledged to exceed (as they have amply done). Its tag line came from President Faust’s address, where she ended with a drumroll of Harvard accomplishment and excellence, each new achievement heralded with a resonant “At Harvard….”

Launching the public phase of an unprecedented, and critically important, capital campaign, in September 2013

For all the dollars raised and buildings built or spiffed up, in one perspective the campaign is curious, particularly given its size: it is associated less with identified new academic programs or faculty expansion than with shoring up the University after the shattering losses of 2008-2009 and defending it against an uncertain new century—in which income from tuition, endowment investments, and federal research support all seem much less certain than they did at the end of the last millennium. Seeking more than $1 billion for financial-aid endowments, for instance, makes it easier to fulfill prior promises and to cope with escalating costs; that, in turn, will give deans more leeway to use whatever future tuition revenue they have to invest in new programs. Similarly, as FAS raises half a billion dollars for professorships, nearly all those funds are designated for endowing existing positions—again, freeing dollars for future academic priorities as they arise. House renewal represents a huge investment in deferred maintenance.

The one clear area for significant expansion traces back to that 2007 reflagging of engineering and applied sciences as a new school, SEAS: the FAS campaign sought some $450 million for SEAS, and the University assigned itself the task of raising the $1 billion or so required to rehouse the expanding school faculty in its new Allston research and teaching complex. Given SEAS’s relatively small faculty cohort and endowment at its creation, these commitments are of a piece with the rest of the campaign’s focus on reinforcing Harvard’s balance sheet as much as possible, to be ready for the future, come what may. (Of course, SEAS, with a $400-million naming gift for unrestricted endowment, and the public-health faculty, similarly blessed to the tune of $350 million, were put on a new foundation as a result of the largesse that campaign planners hope for, but can never bank until those great benefactions arise.) Updated June 19, 8:10 a.m.: The University today announced a small piece of the larger Allston SEAS puzzle: a gift from Cihang Foundation, affiliated with HNA Group, the Chinese tourism, logistics, and financial-serices conglomerate, to fund the 5,000-sqare-foot “maker space” in the new complex.

In this sense, Faust and deans like FAS’s Michael Smith deserve plenty of credit. For all the excitement of seeding new programs, cutting ribbons, and fulfilling faculty members’ dreams, they have, to a considerable extent, committed themselves to the essential work of funding past promises, addressing deferred maintenance, and enhancing future deans’ financial flexibility. Rewarding though those achievements may be, they lack some of the fun that one associates with capital campaigns.

The resumed work in progress on the new engineering and applied sciences complex in Allston, shown this week via the construction cam: a sign of restored financial confidence and the University and campaign focus on computer science, engineering, and allied fields

Nonetheless, the University has managed to find its way forward on a number of cherished priorities, while proceeding on a more economical model than it might have pursued in the past. For example:

- Although the full arts task-force recommendations remain to be implemented, Faust was able to fund an undergraduate Theater, Dance, and Media concentration within FAS—at least a significant down payment on the arts and performance agenda. (Perhaps as a sign of Harvard’s new operating model and constraints, much of the program is staffed by non-ladder teachers.) Combined with the reopening of the Harvard Art Museums, and the new uses they accommodate, this represents a significant investment in arts and humanities, alongside joint ventures such as the FAS-Graduate School of Design undergraduate track in architecture studies.

- The science and engineering complex is now under construction again, with SEAS as the tenant and occupancy scheduled for 2020. In addition to making this perhaps the signal priority of the campaign, resuming construction was predicated on adopting a less expensive design and including renovated space in an adjacent building. Earlier, at the corner of North Harvard Street and Western Avenue, Harvard had jump-started Allston development by partnering with a local builder to erect an apartment and retail complex; and the University is now pursuing long-range plans to develop 36 acres of land farther east along Western Avenue, toward the Charles River, as an “enterprise research campus”—again exploring ways to have private parties assume onerous capital costs, and perhaps hoping to develop a future stream of rental revenue and intellectual-property income, all via what financiers might call an “asset-light” model.

- Similarly, the recently announced data-science institute is being peopled with a new cohort of professional staff members and postdoctoral fellows; no additional faculty appointments appear in the plans disclosed so far.

- Harvard has also continued to expand its international outposts—many of them modeled on Harvard Business School’s global network of research and teaching centers—but it has been cautious about making University-wide, fixed-cost global investments. Instead, it has opted for specific opportunities enabled by donor support, overseen by a “Harvard Global Institute.”

In each case, Harvard is pursuing a course of action that enables it to advance its academic ambitions while minimizing capital investments and fixed costs to the extent practicable—a model for many future initiatives.

Elsewhere, the University has taken the plunge.

With donor support, Faust launched a Harvard-wide initiative on learning and teaching, meant to spark faculty conversations, pedagogical innovation, and experiments with hands-on learning, flipped classrooms, and more. Some of those funds, plus additional donor support and central administration assessments on the faculties, have underwritten the investments in staffing, facilities, and equipment for HarvardX, the online learning venture with MIT, announced in the spring of 2012. Although the results of the former will accumulate gradually, with Faust’s visible support, it has already shifted campus awareness of and focus on pedagogy and teaching, and spawned interesting programs in several schools. HarvardX, like other providers of massive open online courses (MOOCs), needs to find some financial model to sustain operations (particularly because the professional schools have carved out their revenue-producing courses, as in the business school’s HBX and the Medical School’s new HMX venture)—but it has reached millions of new learners worldwide and proven the efficacy and appeal of exciting new technologies.

And, alongside the unending work of raising several billion dollars, Faust and Harvard treasurer (and Corporation member) Paul J. Finnegan have recently undertaken a thorough transformation of endowment management, after persistently lagging results from Harvard Management Company have continued to constrain University finances in the wake of the financial crisis, the imposition of new, more risk-averse investing rules put in place then (no more leverage to boost returns; greater liquidity), and the recurrent changes in HMC’s leadership. The need to act was evident: spending from the endowment, coupled with below-target investment returns, reduced its value in real (inflation-adjusted) terms to billions of dollars below the figure at the end of the last decade—even as it must support a larger institution. Despite the fruits of the campaign, FAS (highly dependent on endowment distributions) again expects to operate at a small loss in the coming year, and the medical school continues to do so. Faust has declined to kick this important can down the road to a successor.

Giving Voice to Values

If Drew Faust is credited with overhauling Harvard governance for the next century or two, and with disciplining its fundraising to meet its most pressing current needs, she will also be associated with asserting and acting on certain values.

Among the foremost of these is diversity, in all its dimensions. As noted, she made enhanced undergraduate financial aid one of Harvard’s largest commitments early in her presidency, and then stayed the course during the extended fiscal pressures following the endowment losses and ensuing budget constraints; the percentage of first-generation students in the College has risen to the current level of 15 percent.

Faust has made a series of diverse appointments, notably among them the deans of the schools of business, design, and, most recently, public health.

An historian of the Civil War, she put significant effort into determining and then publicizing Harvard’s early involvement with slavery, and then broadened discussion of the issue at a Radcliffe symposium this past spring.

As campuses, including this one, have grown more diverse, and their conversations have taken new directions—internally, as new kinds of people meet one another on new terrain, and under the pressure of external polarization—Faust has used the bully pulpit to make the case both for multiple voices and for open-minded, inclusive listening, on occasions ranging from Morning Prayers talks to an argument from her most recent Commencement afternoon address on free speech.

The conversation on diversity and inclusion continues, as it probably always will. The passionate debates within FAS during this past academic year did not dispel objections to the sanctions Harvard College dean Rakesh Khurana has put in place for members of unrecognized single-gender social organizations (final clubs and fraternities and sororities), beginning with freshmen who enroll this August. Those measures have enjoyed strong support from Faust. Both have maintained that such organizations are at odds with Harvard’s values of diversity and inclusiveness; even among faculty members who very much dislike the clubs, questions remain about the appropriateness and efficacy of the sanctions, students’ freedom of association, and the faculty’s role in setting policy for student life.

Seeking to advance conversation on inclusiveness more broadly—against the background of concerns expressed by black students about the campus environment, heightened attention to sexual assault, and evidence of sexism and gender disparagement (among members of athletic teams, for example)—Faust created a Task Force on Inclusion and Belonging, which is now at work preparing University recommendations for next spring. Hints about some of the underlying currents within the community arose during Commencement, with the first Harvard Black Commencement and the third iteration of a LatinX graduation. Throughout her tenure, as in her youth in Virginia during the battles over school desegregation, Faust has been attuned to, and engaged with, America’s enduring, and in some ways widening, struggle over discrimination. It is entirely consistent with those concerns that she has spoken out about President Donald Trump’s proposed limits on immigration since they were first issued.

A separate issue that arose during her administration—academic misconduct—has engaged different values, and has persisted in troubling ways. During the 2012-2013 College investigation of academic misconduct, Faust articulated “the highest expectations for our students,” and the processes that should be followed in addressing cases of possible misconduct. But for the most part, remedies took the form of FAS legislation that created a new honor code and honor council (including student members) to hear cases of possible violations. The Harvard Crimson’s report this past spring that several dozen students had been investigated for possible violations of the standards established by the gateway computer-science course last fall (the outcome of those cases is not yet known) suggested that problems remain in promulgating those standards, eliciting student compliance, or getting all participants to understand and adhere to community norms—or a combination of those factors.

Although student and faculty advocates of divesting Harvard investments in fossil-energy enterprises will certainly not see it this way, Faust and the Corporation determined that the University’s standards for social investing and divestment were properly drawn, and insisted on adhering to them. That decision cost Faust some of the bluntest criticisms and protests directed at the administration during her tenure. She responded sharply, insisting that criticisms be made with “respect.”

Across this spectrum of concerns—diversity and inclusion; regulation of clubs and organizations and students’ choices; speech; external issues like immigration; and academic conduct—all presidents of universities today have to engage in conversations about their values, and their universities’. By choice and circumstance, that has been especially the case during Faust’s presidency.

In Prospect

What next? For Faust, after another year on the fundraising circuit, making the University’s case in Washington, and in faculty meetings, one hopes for more time with her young dog, Alice, more time for mystery novels, and more time to catch up on missed episodes of favored television series (she is a confessed Breaking Bad fan, for instance).

The immediate parlor game will be handicapping the succession. An effective One University dean/curriculum reformer/globalist/prodigious fundraiser like the business school’s Nitin Nohria? A curricular change agent who has shored up an under-resourced school and begun renewing its faculty (and who is involved with a key social priority to boot), like the Graduate School of Education’s lawyer-dean James E. Ryan? Some scientific star, able to make the case for basic research—but also to articulate the enduring value of the humanities and arts? An ascendant faculty member, like Danielle Allen—appointed to a University professorship on a fast track, and now co-leader of the inclusion task force? Or—venturing beyond Crimson parochialism—an outsider?

No doubt, there will be a betting market, and plenty of time for gossip and social-media rumors.

For Harvard, the real work goes on. The Corporation, and prospective presidents, have plenty to consider.

- The Trump administration’s apparent desire to slash funding for biomedical research has grave implications for FAS and the Longwood Medical Area—and runs head-on into the Corporation’s strategic emphasis on investing heavily in life sciences (discussed here by senior fellow William Lee). It would be hard to imagine a more expensive field in which to expand—so one issue will be determining whether The Harvard Campaign could be succeeded by a focused, snap effort aimed at biomedical opportunities. (Shirley Tilghman, the Princeton president emerita and a distinguished molecular biologist and geneticist, led a review of life sciences at Harvard before her Corporation appointment in 2016. Other straws in the wind, or hedges against leaner public support: George Daley, the new medical dean, has deep ties to the biotech and life-sciences venture-capital communities; and Alan Garber, the provost, was just elected to the board of directors of Vertex Pharmaceuticals—following the earlier example of Faust, who became a director of Staples Inc. after her election as Harvard president.)

- More broadly, what is a sustainable financial model for the University? Fixing the endowment is the largest immediate priority. Further expanding executive education is an attractive source of revenue (although it comes with associated expenses and demands on faculty time). During the past decade, Harvard has grown in facilities, budgets, and operating expenses, but the ladder faculty has not—nor has the resident-student population to any significant extent. Whither from here, especially if research in engineering and applied sciences and life sciences are to expand significantly?

- Most important, as the Corporation moves beyond the immediate priority—making The Harvard Campaign as successful as possible, and bolstering the University’s fisc—what distinctive strategies will it and future presidents define? What faculty members, facilities, global engagements, and pedagogical technologies follow from that? Surely there will be crises in the future, but perhaps the next president will be spared crisis management to the extent forced upon Faust’s administration; if a successor enjoys such breathing room, will she or he focus Harvard’s energies and strategies further—in an era when doing everything is probably not possible, nor even desirable?

Weighty, and worthy, matters all.

Harvard, and President Drew Faust, can feel very good that after a prematurely shortened presidency in the prior decade, and a truly frightening financial and organizational crisis a few years later, the institution is in excellent shape to address these momentous issues deliberately and appropriately today.

Read the University account of Drew Faust’s presidency here.