Houghton Library was conceived in 1924, in a letter by Archibald Cary Coolidge, director of the Harvard University Library, who imagined an “enchanted palace on the raised ground close to Widener.” Consistent with the times, and with his very name, he envisioned the repository in elite terms: “a beautiful building…in which we store all our works of great rarity and value…[and] works dear to the book-lover, a place where we could keep what we valued most and show it to those who appreciate it….”

The vision became reality with the support of Arthur A. Houghton Jr., assuming the now-familiar form upon its dedication on February 28, 1942—following the infusion of 125,000 volumes from Widener. By then, of course, war raged around the world, ultimately costing many millions of lives, and threatening or destroying so many other artifacts of the cultures that the new library itself was meant to protect: treasures that have been collected through nearly four centuries now, and safely housed in Houghton for 75 years.

Coolidge’s correspondence, and conception of the library, appear in the introduction to Houghton Library at 75 by Heather G. Cole, assistant curator of modern books and manuscripts, and John H. Overholt, curator of the Hyde collection of Dr. Samuel Johnson and of early modern books and manuscripts. They cheerfully address the impossible task of portraying the collections through several dozen samples—from familiar, if stunningly gorgeous, illuminated manuscripts through the First Folio of Shakespeare to (perhaps surprisingly modern) ephemera: a tape recording of Sylvia Plath, from the Woodberry Poetry Room, and recent comic books featuring black heroes.

The holdings, they note, “represent the scope of human experience from ancient Egypt to twenty-first century Cambridge,” thus embracing “nearly the whole history of the written word, from papyrus to the laptop.” But the weight of past collecting dictates that the library’s strengths remain “primarily in North American and European history, literature, and culture,” albeit ranging “from printed books and handwritten manuscripts to maps, drawings and paintings, prints, posters, photographs, film and audio recordings, and digital media, as well as costumes, theater props,” and other objects, maintained in eight curatorial departments. Augmenting the collection today presents new challenges, reflecting the evolution of interdisciplinary research—not least toward “uncovering suppressed or underrepresented voices” that extend “beyond the privileged, white, male voices that traditionally dominated Houghton’s shelves.”

The other imperative is use: supporting scholars, making materials available for teaching. “Houghton Library was born into a world still ruled largely by paper—not just in its collections, but in the systems by which those collections were managed,” Cole and Overholt note. “Researchers…filled out paper slips to request the materials they wanted to see. Those who could not visit in person sent letters of inquiry, and reference librarians responded with typewritten replies, with a carbon copy kept for the library files.” The restrictive whiff of Coolidge’s “those who appreciate it” is not entirely dissipated (the hush remains palpable), but it is certainly broadened by a powerful urge to extend access—where practical, digitally.

The book, a thing of beauty in itself (see page 41), is complemented by a series of exhibitions and events. On the following pages appear samples from the first major exhibition, “Hist 75H: A Masterclass on Houghton Library”(on display through April 22). That title conveys the librarians’ external focus, on teaching with and use of the collections. It also suggests the show’s contents—diverse items chosen by 46 faculty members based on their strong connection with the selections: a discovery from their undergraduate experience, a pillar of their research, or an exemplary part of their current courses. The items are accompanied by the exhibition labels crafted by each faculty member, and audio excerpts (from curators’ conversations with them) explaining something about the object on display—all coordinated by reference librarian James M. Capobianco. A tour, in other words, of the collections, their use, and contemporary humanistic scholarship. Visitors are welcome to enroll.

Subsquent exhibitions will feature works chosen by the curatori∂al staff, and an important modern acquisition, plus displays on Houghton’s history, collecting, Henry David Thoreau in his bicentennial year, and more. Complete details are available, digitally of course, at Houghton75.org.

~ Jennifer Carling and John S. Rosenberg

Photograph by Jim Harrison

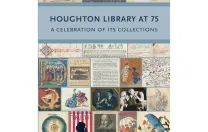

Sighting Whales, Then and Now

Navigation has been taught at Harvard since 1718, initially as a way to illustrate the mathematics of spherical geometry. Since then, the teaching of navigation has become more applied and the pedagogies used far more “hands-on.” Astronomy 2 has expanded during the last 25 years to utilize the University’s great collections of instruments, maps, and rare books, like this log from the Bark Canton. These two pages follow the weather and winds experienced while still near the coast. Once leaving sight of land, entries will become less colorful, but still full of meaning: hourly records of course, speed, winds, and calculation of latitude and longitude.

Logbook of the Canton, from New Bedford to Australia, 1874-1878

Not all [students] were impressed by the theoretical approach [to teaching navigation], as Henry David Thoreau commented in 1854, “To my astonishment I was informed on leaving college that I had studied navigation! — why, if I had taken one turn down the harbor I should have known more about it.”…Beginning with astronomer Robert Wheeler Willson’s Celestial Navigation course in 1896, students learned surveying to map out Cambridge Common and the use of chronometer and sextant to find latitude and longitude, while not skimping on theory….These two pages…dutifully illustrate the profiles of known islands and dangerous rocks, information that may be lifesaving in the future, all while eyeing the quarry of sperm whales.…Students reproduce all of these [traditional measurements] during our own “turn down the harbor,” a cruise 40 miles east to Stellwagen Bank, to be entertained by the now safely cavorting humpback whales.

— Philip M. Sadler, Wright senior lecturer on celestial navigation and astronomy; director of astronomy education, Harvard College Observatory

Photograph by Jim Harrison

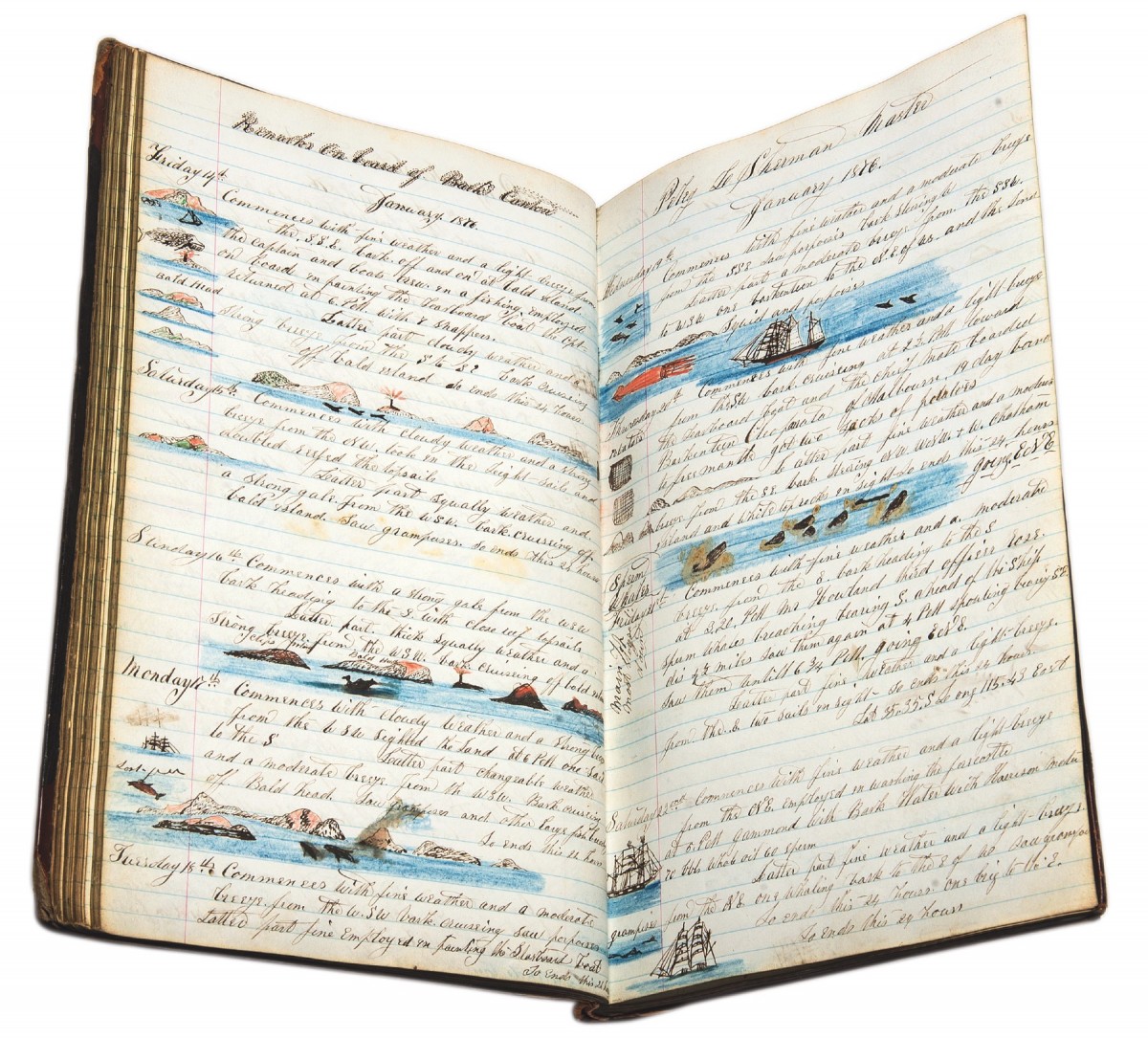

A Medieval Tale, Remixed

Adaptations of medieval material in modern culture can be fascinating. “Le jongleur de Notre-Dame” is earliest attested in a beautiful thirteenth-century French poem. First edited in 1873, it made a big splash after being adapted in 1890 by a future Nobel prizewinner. In turn, Anatole France’s short story inspired a 1902 opera. Tony Curtis starred in a 1960 made-for-television movie based on the story, and the poet W.H. Auden wrote a ballad. Fritz Bühler produced 50 hand-painted copies of France’s story as Christmas gifts in 1955. A Swiss graphic artist, he helped to design and promote the Helvetica typeface.

“Le jongleur de Notre-Dame.” Adapted by Anatole France, designs by Fritz Bühler. Bâle: Editions St. Alban, 1955

— Jan Ziolkowski, Porter professor of medieval Latin and director of the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

Courtesy of Houghton Library/Harvard College Library Imaging Services

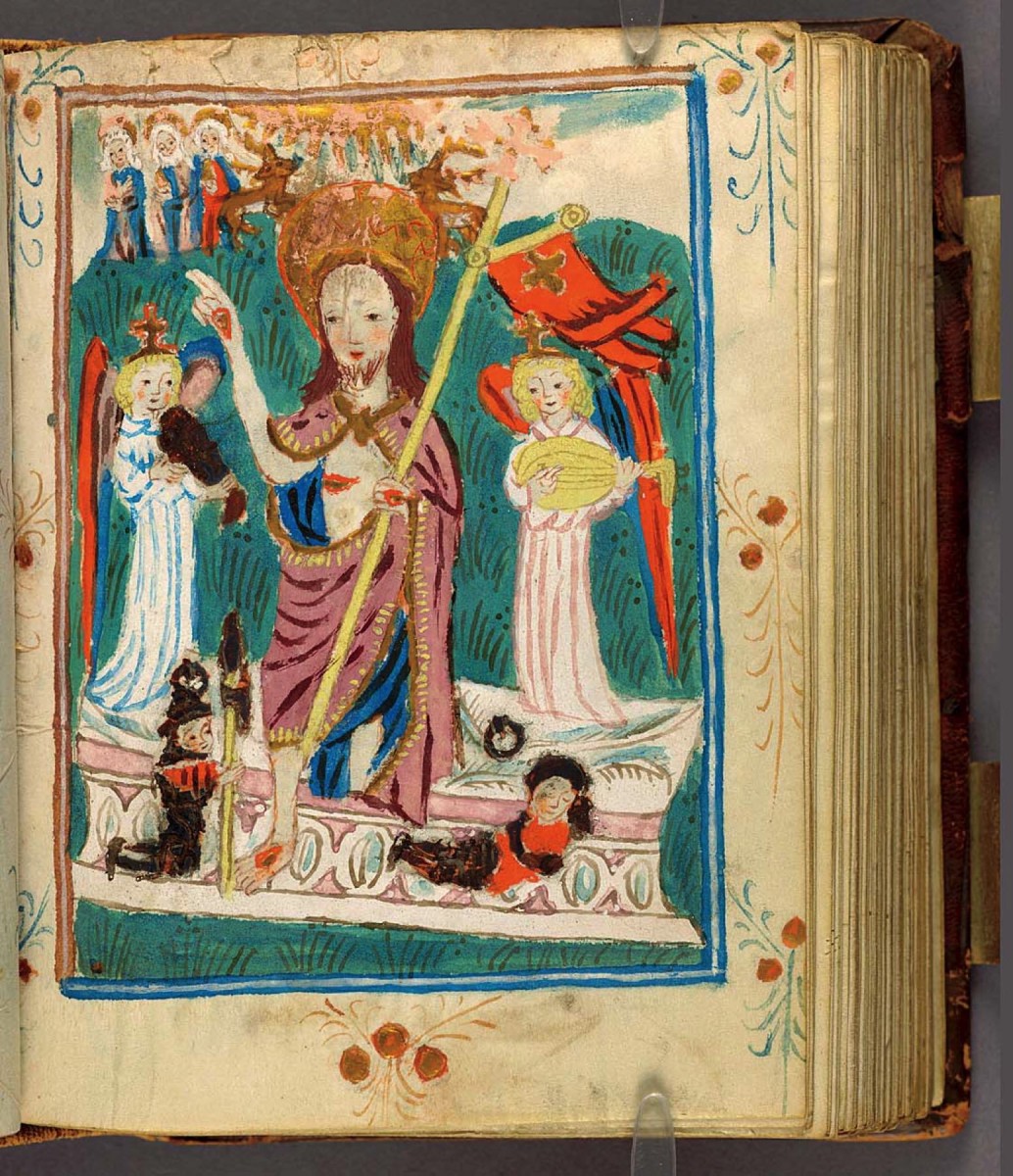

An Easter Prayer Book

This Northern German Easter prayer book…forms part of a larger collection of the Cistercian nuns of Medingen, who were extremely skilled in the production of highly valuable liturgical and devotional books. This particular book contains Latin prayers and Middle Low German songs alike. The interspersing of vernacular language has, however, nothing to do with the purely visual element of the changing ink color between red, blue, green, and black.

Fifteenth-century manuscript

[T]he pages that are open show a whole-page illustration, a so-called miniature…and we see in the center a dominating figure…representing the resurrected Christ. He’s got his hand out as [if] to bless, he’s wearing a royal gown that just covers his body slightly to reveal four wounds. One foot is still in the tomb, and that’s quite interesting because sometimes you would find him with five wounds. [S]ince we cannot see one foot we don’t really know. Now the wounds are also illuminated with gold, and you can see there’s a lot of gold applied on this page.…[T]he illuminations fulfill different functions. For the wounds, this is of course to also show that this is the resurrected Christ….

The other reason is that it draws attention to the passion of Christ as a central topic for the contemplative practices at the time. The colors…applied in this miniature will also reappear throughout the manuscript.…

The text facing the miniature speaks about the glorious Pascal day and the joyful music that is sung on that day and you see then the angels with two medieval instruments, and that’s another way to link the celestial realm to the actual monastic practice of celebrating that day and unifying the humans’ song with the angels’ song.

— Racha Kirakosian, assistant professor of Germanic languages and literatures and of the study of religion

Photograph by Jim Harrison

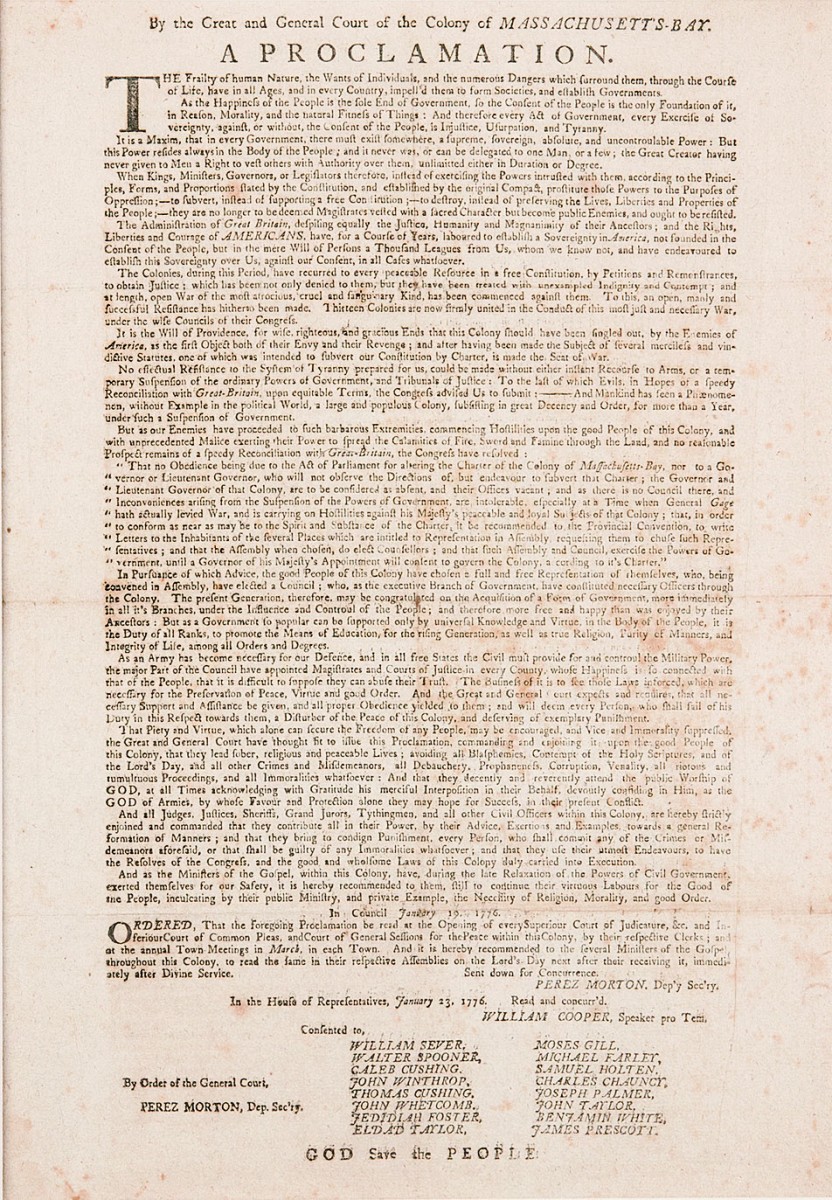

The First Draft of the Declaration of Independence

One of the main arguments of my book, Our Declaration, is that John Adams deserves just as much credit as Thomas Jefferson for the argument and rhetoric of the Declaration of Independence. Adams, for instance, more than anyone else focused his contemporaries’ attention on the concept of happiness, and key phrases, like “course of human events,” reflect his rhetorical style. This year at the Houghton, thanks to John Overholt, I found, lo and behold, the smoking gun…a veritable first draft of the Declaration.

John Adams, A Proclamation: The Frailty of Human Nature,

Watertown, Massachusetts, printed by Benjamin Edes, 1776

My main research focus…is on political equality, and the American Declaration of Independence is a particularly profound and influential statement about political equality.

I’ve worked on the Declaration for some time now, and one of the most important stories…is the story of John Adams’s role in driving the politics that led to the Declaration and in generating the arguments for the Declaration. And in fact I’ve been going around the country making the argument that the only reason we think Thomas Jefferson is the author of the Declaration of Independence is because he put that on his tombstone. If he hadn’t…we might know the truth, which is that multiple people participated in producing the text of the Declaration and John Adams was one of the most important….

So I cannot tell you how excited I was when I came over to the Houghton…and discovered Adams’s Proclamation by the General Court from January 19, 1776.…So at last I had my final piece of proof.…[H]ere is a text that has…exactly the same structure as the Declaration of Independence six months before the Declaration. Not only does it have exactly the same structure, but it has the same language. It is the first version of the Declaration of Independence.

— Danielle Allen, Conant University Professor

Courtesy of Houghton Library/Harvard College Library Imaging Services

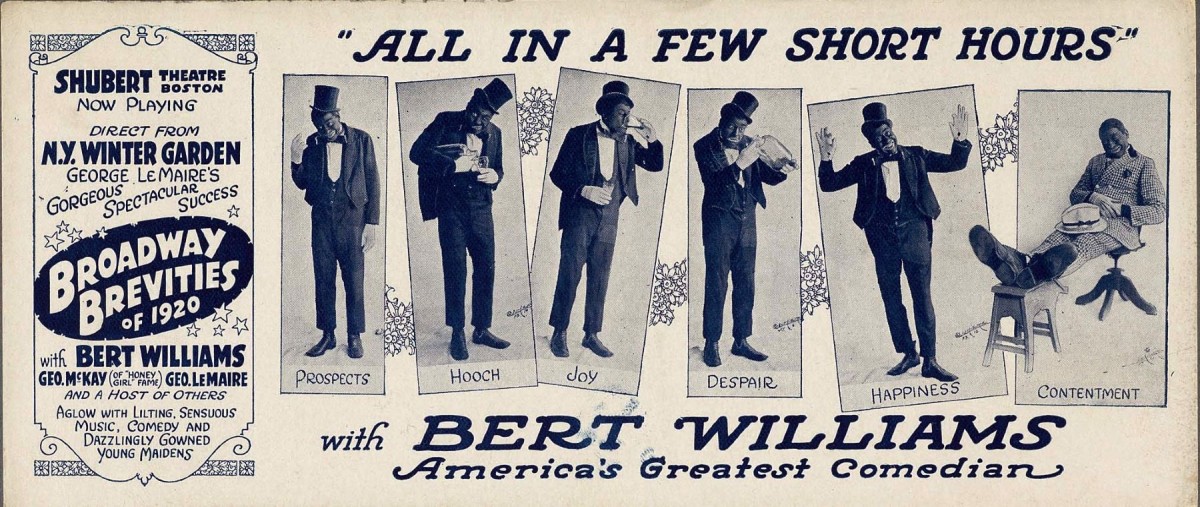

An African American in Blackface

Billed as “America’s Greatest Comedian,” the African American performer Bert Williams (1874-1922) emerged out of minstrelsy to achieve extraordinary success on stage. His career was defined by Jim Crow segregation. Yet Williams disrupted racial barriers to headline otherwise all-white revues, starting with the famous Ziegfield Follies. He consistently put on blackface, a tradition of darkening the skin with burnt cork that was central to minstrelsy.

In this advertisement for the Broadway Brevities, a revue that traveled from New York City to Boston’s Shubert Theatre, Williams appears in blackface with his characteristic top hat, tails, and white gloves. The series of photos poke fun at Prohibition, which had gone into effect in January 1920. Advertisement, 1920

My work is focused on twentieth- and now twenty-first-century American music and its broad-ranging cultural contexts, and increasingly I have been working on race from the perspective of racial integration and desegregation.

This flyer…is just an amazing testimony to the importance of ephemera, and it tells us so much about its era. The performer featured…is…hailed by many as one of the greatest American comedians of all time. Although this flyer is from 1920, he’s a figure who hails to two decades earlier, an era of a cluster of composers, performers, music publishers, producers, all African American, who for a period of 12 to 15 years were successfully producing shows on Broadway.

Now the shows…were largely grounded in what at the time were called “coon songs,” songs that traced a legacy back to blackface minstrelsy…a way to gain access into the world of entertainment, to get a job, to have a career.…In this flyer he’s wearing a tuxedo and top hat, which is so interesting because on the one hand that gestures to the “Zip Coon” stereotype of blackface minstrelsy, but it also feels like he’s pressing…beyond it. His tux isn’t tattered. It has some kind of elegance to it. It’s all really poignant when you just pause over the racial issues that this man was coping with.

— Carol Oja, Mason professor of music

Photograph by Jim Harrison

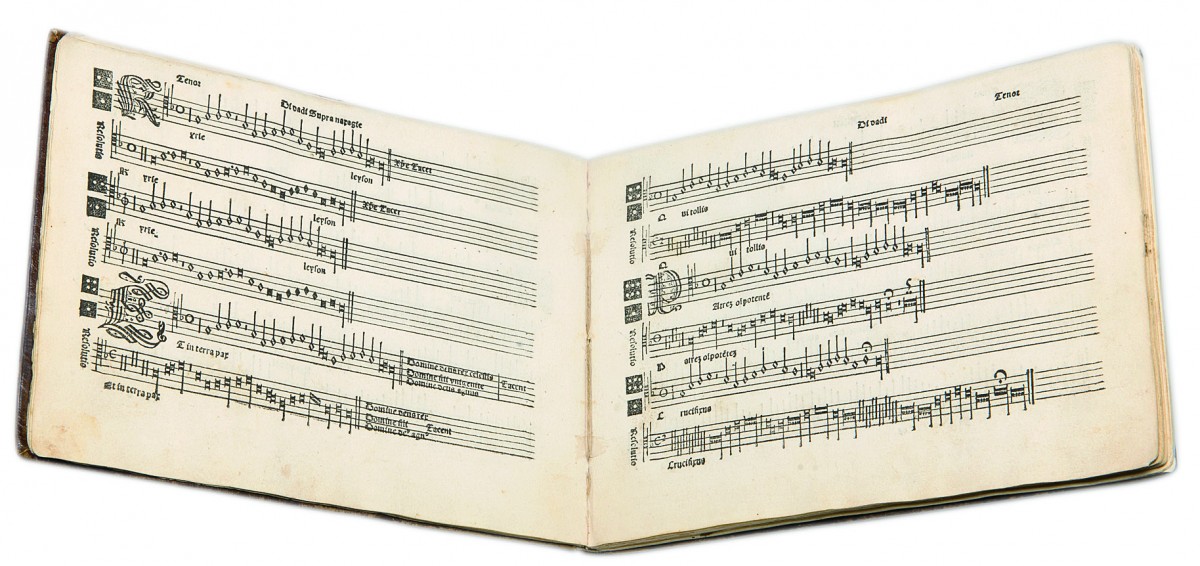

Early Printed Polyphony

This rare partbook probably survived thanks to the charming dice featured in Josquin’s Missa di dadi, which show singers in which proportion to render the tenor part (also realized just below). The melody comes from a love song with the text “Shall I never have better than I have?”—here transformed into an allusion to the gamblers’ attempts to beat each others’ throws.

Note the fine presswork, with the staves printed first and the notes printed in a second impression, a method developed by Ottaviano Petrucci, the first printer of polyphonic music books.

Josquin des Prez Tenor partbook, 1514

[This] book…is one of the first examples of a new printing technology for polyphony. Ottaviano Petrucci, who solved this particular problem of putting typographical notes on the page along with their linear staff lines, did so by running each sheet through the press twice… And then also, if you look at the big “K” at the beginning of “Kyrie,” with woodblocks for those large initial letters.

This book is one of four partbooks, each with its own vocal line to the Mass.…The tenor had a particular job in this piece, which is to sing one piece of plainchant over and over again, but each time in a different mensuration and prolation, meaning that the notes were different lengths. Now the dice on this page show the tenor singer what mensuration and prolation to use [and] here Petrucci has included the resolution underneath each line. And you can see each time it’s different.

[T]he dice…also allude to the melody of this song, which…here is an allusion to the gaming of dice players, and also has a sacred allusion as well.

— Kate van Orden, Robinson professor of music

Photograph by Jim Harrison

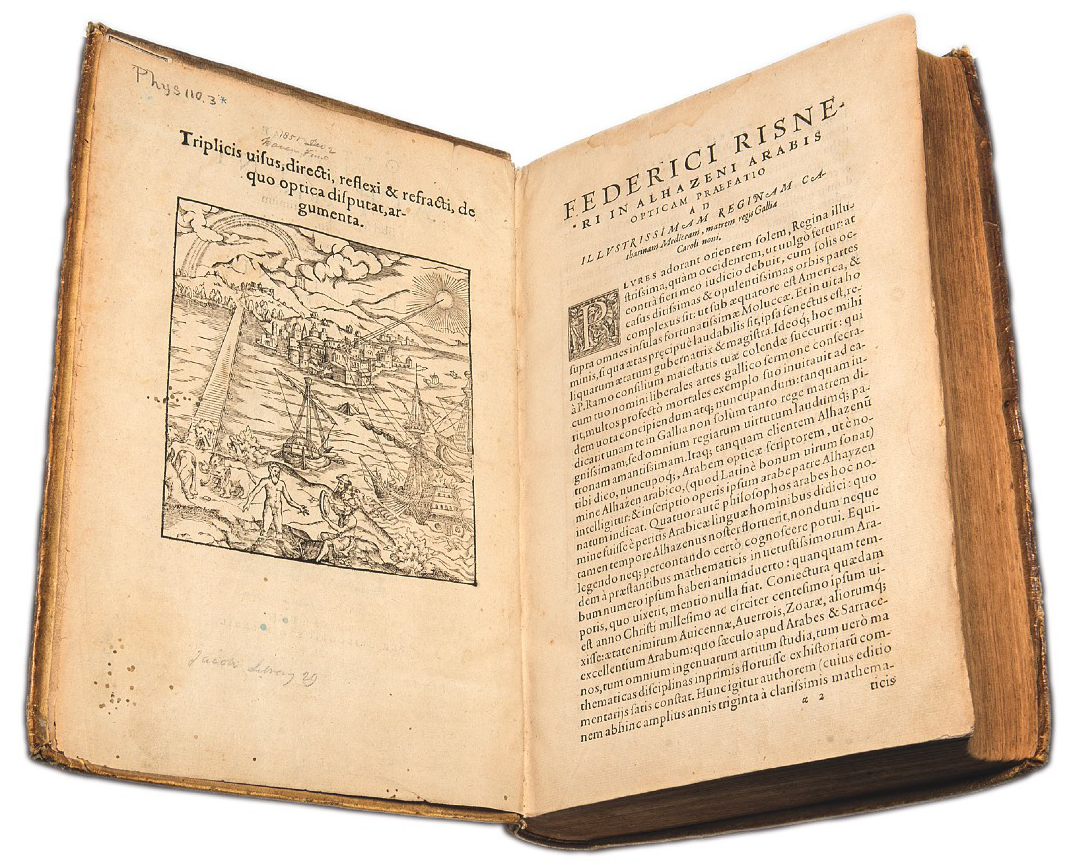

The Spread of Science

This printed edition of the Latinized Optics [Opticae Thesaurus] of Ibn al-Haytham, the eleventh-century scientific author in Arabic known in Europe as Alhazen and Alhacen after his first name Al-Hasan, has been prominent in my teaching and research….This text represents an important chapter in the history of optics and perspective as well as experimental methods and conceptual breakthroughs. Translated from Arabic into Latin, then Italian, with a much larger impact in Europe than in Islamic lands, it also represents an outstanding case in the transmission and transformation of early scientific works.

Alhazen (965-1039), Opticae Thesaurus, 1572

I am a historian of science….

Although this book is on optics and from Europe of the early modern period, it represents subjects, figures, mediums, languages, places, and times much beyond what is embodied between the covers of its single volume. The main subject contained in it is much broader than the specialized subject…that optics became through time. Pre-modern optics focused on vision, and through it, related subjects from early perception and natural philosophy to pre-perspective geometry and epistemology.…

Besides subjects and figures, the work is of interest for representing mediums beyond print, and languages beyond Latin. Its seven books were originally composed in Arabic, not Latin, and in manuscript form, not print.…The work’s seven books were transmitted internally mainly through a thirteenth-century commentary by an author named Kamal al-Din Farisi, but externally through more than one medieval Latin translation from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, an Italian version from the fourteenth century, and this printed Latin edition from the sixteenth century, making [its] impact…especially far and wide.

— Elaheh Kheirandish, postdoctoral associate of the department of history of art and architecture [Editor's note May 1, 2017: Elaheh Kheirandish writes to suggest that a corrected date of death for Alhazen would be d. post ca. 1040-41, instead of 1039-1040 used in the Houghton materials.]

Photograph by Jim Harrison

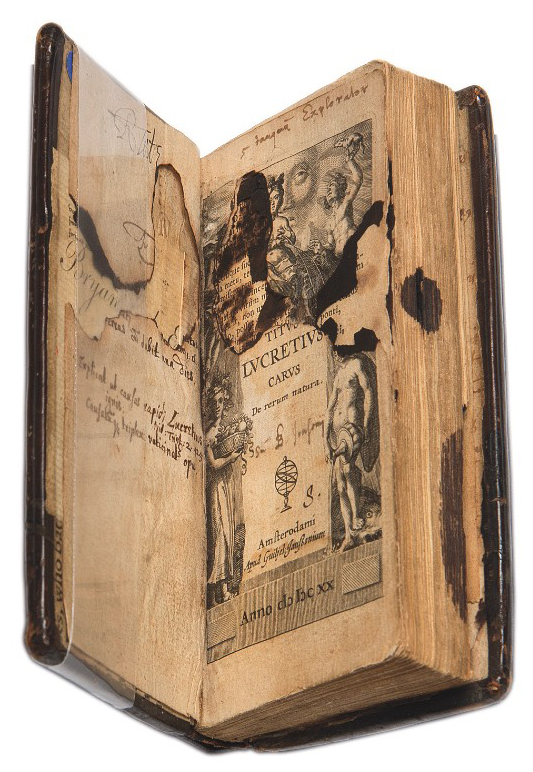

Ben Jonson, Hard on Books

It is easy to imagine the poet and playwright Ben Jonson carrying his handy copy of Lucretius’s philosophical poem, De rerum natura, around with him and discussing its subversive, epicurean arguments with his cronies. On one of these occasions, they evidently played a game writing rhymed Latin couplets against the Puritans. Jonson wrote these down on the blank pages at the end of the book. At this or another time the poet—who was a famously heavy tippler—or one of his friends evidently spilled ink, corrosive due to its high acid content, on the opening pages.

Ben Jonson’s copy of Lucretius’s De rerum natura, 1620

[T]his copy of De rerum natura was printed in 1620 in Amsterdam. There were many editions of Lucretius at this point, many of which had elaborate commentaries. This doesn’t have a commentary. It’s the text itself and it’s remarkable for a number of reasons, but perhaps most of all because it was owned by Shakespeare’s friend and rival, the playwright and poet Ben Jonson.

Jonson seems to have been responsible for the damage to this book, though we can’t be sure. Someone, in any case, has spilled something that has damaged the pages. Ben Jonson…might have been in the tavern with his friends and spilled it and tried to brush it off, but it’s damaged the pages. At the very back of this book, there’s evidence of the peculiar occasion in which at least it once was read and exhibited because Jonson and his friends, perhaps, have written a poem, not a very good poem but in rhymed doggerel couplets against Puritans, in the back of the book in Jonson’s hand.

This…was one of the most interesting and resonant books of classical antiquity because it challenged so many of the basic views of Christians in the Renaissance and indeed up ’til the nineteeth century. In…1620, still relatively few people had read this poem. You had to have lots of Latin, and you had to have lots of interest in a very disturbing account of the universe.

— Stephen Greenblatt, Cogan University Professor

Courtesy of Houghton Library/Harvard College Library Imaging Services

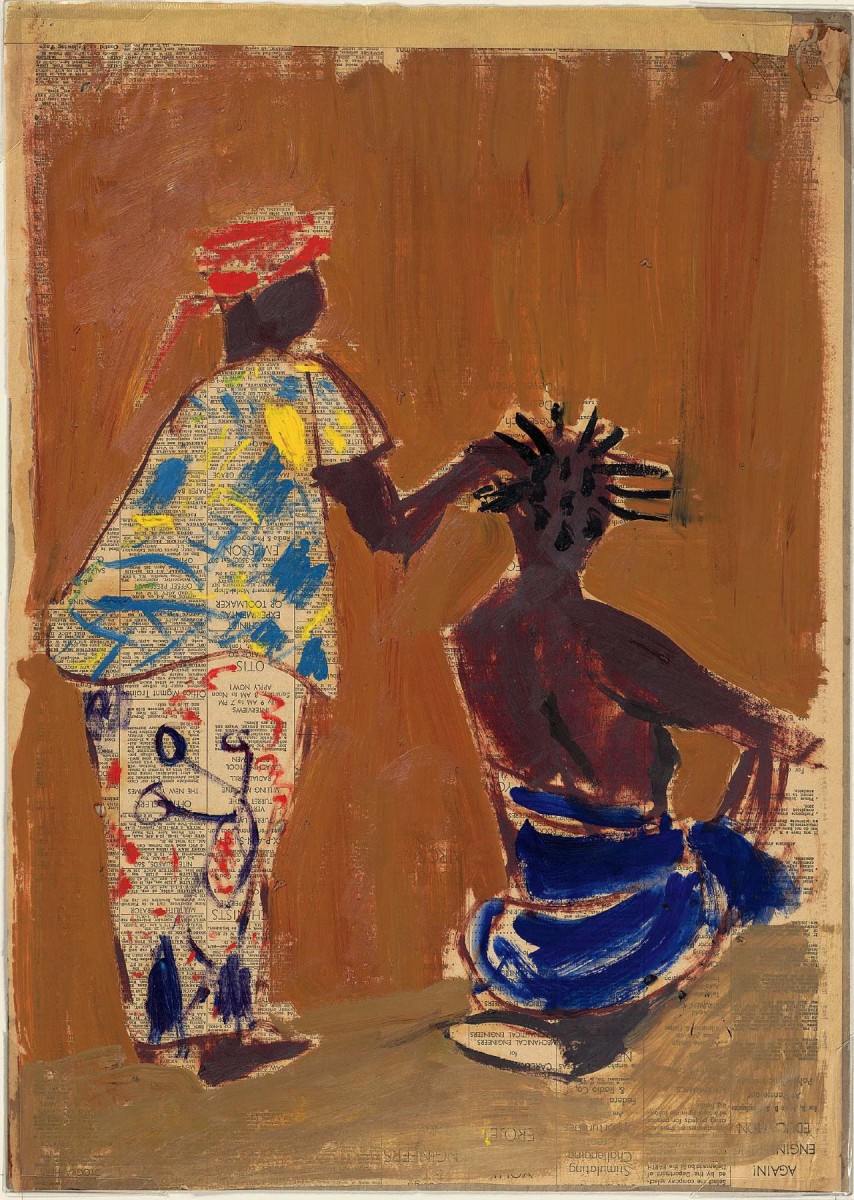

Bridging Worlds in a “Beauty Salon”

Anne Eisner, a New York painter and my aunt, lived at the edge of the Ituri rain forest from 1946-58 (now Africa’s Democratic Republic of the Congo). Working on her archive for publication of Images of Congo, I realized how much her passion for relating culture and artistic creation had influenced me. Anne bridged the divide between co-existing societies—inside and outside the forest, Bantu and Pygmy—and, deeply engaged in everyday life, celebrated the importance of the women. Beauty Salon figures the care each took of others, and echoes Pygmy bark cloth designs in color-saturated newsprint.

Anne Eisner, Beauty Salon, 1956

Anne Eisner lived for nine years in the Belgian Congo…an experience that took her across both spatial and cultural boundaries. The people of the Ituri rain forest became of compelling interest to researchers and tourists, but before that happened Anne lived amongst at least two groups of Bantu and Pygmies who inhabited the area. What you are looking at is a watercolor that is done from memory in 1955 or ’56.

[H]ere are two Bantu women in what Eisner called their beauty salon. The woman on the left is braiding the hair of the woman who is seated on the right. What I would like you to notice about these two women is not only their connection, that one is taking care of the other, that they are in a society, therefore, of women who are very interconnected, but also the line that separates the bottom part of the watercolor. The line that goes from lower left to slightly higher right.

In many of her depictions…from that period, Eisner draws a line. And the line is generally a line between the inside and the outside. So in this case, you can see that both women straddle the line, and that was very much what she ascribed to these women—that they were able to bridge the world of the colonialists and the world of their own tribes.

— Christie McDonald, Smith professor of French language and literature and of comparative literature, and faculty dean of Mather House